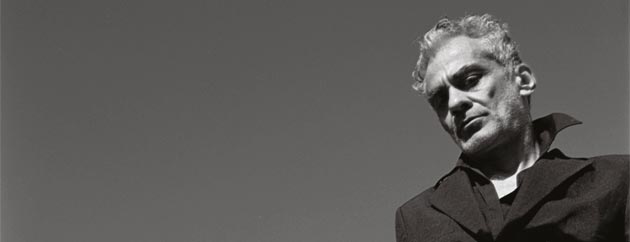

The Brutal Verse of Tango: An Interview With Daniel Melingo

08 November, 2012Before tango took hold of Europe in the early 20th Century, Argentina’s most famous musical export was the tune of gangsters, prostitutes and thieves. It was synonomous with Lunfardo, the local prison slang of Buenos Aires that unifed the city’s underbelly via sexual innuendos, references to drug dens and speakeasies, and melancholic verses expressing pain and destitution. A mishmash of Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and African dialects, Lunfardo developed into a form of dark yet sensual street poetry that would influence countless writers, artists and musicians at home and abroad.

Legendary rocker-turned-tango-singer Daniel Melingo feels deeply indebted to this musical and linguistic tradition, which he continues to explore on his most recent album Corazón y Hueso (World Village, 2011). Melingo has dedicated countless hours to unearthing the rich, twisted world of Lunfardo poetry, which he says is an indelible force not just in tango but in Argentine culture as a whole.

A native of Buenos Aires, Melingo received classical training early on but soon found his way into Argentina’s budding rock nacional scene. He was a member of the influential group Los Abuelos de La Nada with Andrés Calamaro and became a fixture of the genre throughout the 80s, performing with Charly Garcia and other big names. After a brief stint in Spain with the experimental Lions In Love, Melingo took a career-defining risk, diving headfirst into tango with 1998’s Tangos Bajos.

“Long story short, I was feeling musically restless,” Melingo explains to Sounds and Colours on the eve of his 2012 UK tour.

“I had been nourished by classical music through my paternal grandparents, tango through my maternal grandparents, and rock with my cousins. Growing up I had to find my identity within rock, tango and later electronic music, as well as music production (I always liked recordings). My challenge was always genres and styles.”

Melingo says playing with greats like Los Abuelos de La Nada and Charly Garcia gave him a solid foundation in rock and helped him formulate his musical persona. In the late 80s, he moved to Spain, where he explored the vibrant electronic music scenes in Madrid and London at the time. Melingo brought these experiences with him when he made the shift to tango.

“At some point I felt this inquietude to develop tango, so as composer and producer I put together my first tango album already knowing how to record an album of songs outside the genre. I took a risk with that first album, but over the years I’ve been perfecting the style and learning singing techniques. It became another genre that I learned to play and write, just like rock.”

While he appreciates the stylistic differences between rock and tango, Melingo makes a convincing argument that his rock nacional, with its long-haired excess and superstars like Luis Alberto Spinetta and Charly Garcia, is essentially an extension of tango. This connection, he says, can be found in the lyrics.

“Rock nacional and tango are tied together. When rock nacional first appeared in the 1960s, it filled the gap during one of tango’s weakest moments. Our rock is really part of our tango, this sort of father genre that encompasses over 100 years in our musical culture. And in both you find melancholy in the lyrics. In both you find our urban images, our Porteño humor.”

Both genres seem to flow evenly though Melingo’s blood, but when you talk to him you get this deep sense of – call it nationalistic – pride to be playing tango, the music of his city and of his family.

“Every Porteño has their own style, their own ideology surrounding the tango. Tango is very broad, in every sense. It includes many disciplines, not only the music but also the dance, the poetry, etc. So there are many ways to view tango. I’m speaking as a Porteño raised in a tango family. I feel every Porteño has the right to feel tango in a different way, and (luckily) we don’t all agree.”

An indelible part of Melingo’s creative process is the exploration of Lunfardo texts, which he often adapts to music. Through his tireless efforts to transmit these brute sentiments, Melingo has become a kind of historian on the subject. He uses the word buceo (Spanish for “scuba diving” ) to describe his constant discovery.

“Lunfardo began as a slang, later transformed into a literary genre and was indispensible for writing tangos. I dig through a lot of these old poets. In fact I work closely with one whom I believe is the most important Lunfardo poet alive today, Luis Alposta. Through him I investigate new poets in our old literature and I begin formulating my songs. It’s an endless process, but it allows me to develop my own language within tango.”

With the precision of Borges and the bluntness of Bukowski, Melingo crafts atmospheric musical statements that transport listeners to the seedy world of Alposta’s protagonists: drug addicts, drifters, deadbeats and alcoholics. It’s no surprise Melingo’s tango bizarro sound has been compared to that of Tom Waits and Nick Cave.

After months of touring in support of Corazón y Hueso, Melingo is about to play a string of highly anticipates dates in the UK, where he was dubbed “the man who’s making tango seriously cool” by The Independent. A lifelong fan of English rock, Melingo is beside himself.

“I would have never imagined doing a full tour of the UK playing my tango bizarro – which is really influenced by rock, trash and punk – in the country where we rockeros have borrowed so heavily, even more so than the United States.”

When asked about the challenge of performing in non Spanish-speaking countries where even those who speak the language may not understand the Lunfardo, Melingo was confident that his music is being understood.

“These last ten years I’ve played in over 150 cities throughout Europe, with only a couple shows in Spain. What I can tell you is this: our tango evolved from numerous musical genres brought over from Europe. They transformed with the sweat of our city and are now returning to where they came from. So there’s a real understanding due to Europe’s vast musical culture. They identify with the music, they understand it.”

Daniel Melingo is touring the UK from November 7th until November 20th. Full tour dates can be found here

His latest album Corazón y Hueso can be purchased from iTunes and Amazon

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.