Inés, Recuerdos De Una Vida

30 May, 2014Whilst life is invariably fatal, implicit in this process is suffering; to live is to suffer; to suffer is to live. Some get off lightly, but in the end everyone of flesh, bone and blood gets it in the neck. It is just a question of degree and the ability of the subject to negotiate whatever vagaries, burdens and injustices life throws up. Therein lies transcendence. “Life,” though, as Miguel de Unamuno said and Inés’ story testifies, “never surrenders.”

Luisa Sossa’s documentary, Inés, Recuerdos De Una Vida (Inés, Memories of a Lifetime, 2013), one of the documentaries to be screened between 5th-8th June as part of the Colombia Film Panorama in London, Paris and Barcelona, shows us the effects of this suffering through the perspicacity of a woman thought too submissive and beaten to have any.

Having a Legacy to Stand On

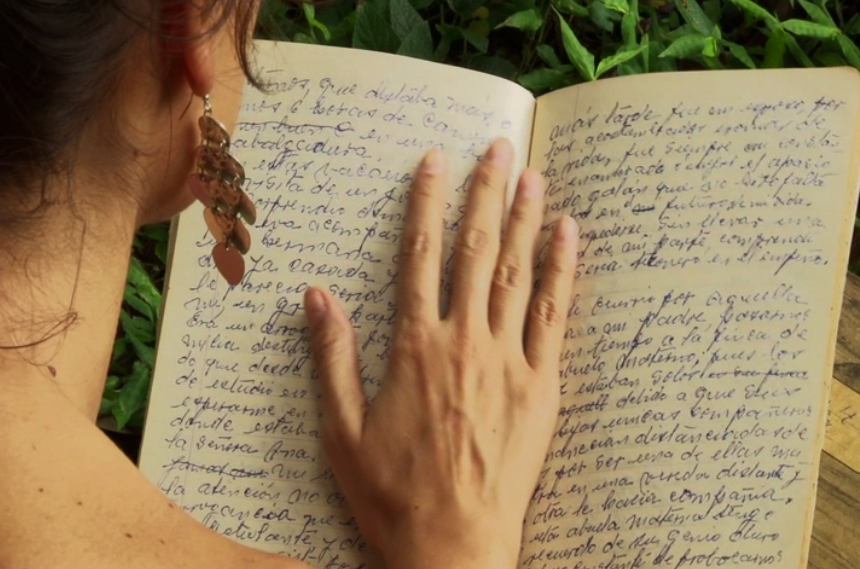

The theme of the documentary is the 10-volume account written by Sossa’s grandmother, Inés Rodríguez de Peláez (1906-1990), left “for her children” and to be read after her death.

The subject matter – marital subjugation, infidelity, brutality and submissiveness – would not be unusual in a Colombian or other context for women who lived during her temporal span.

Born into a conservative country under the watchful eye of a conservative church, you didn’t pick your partner so much as go along with those suitors of whom you family approved. Any love interest had to play catch-up with more mundane considerations. Marriage then, as it continues to be in large parts of the world, was a transaction, a business arrangement.

In this particular instance, Inés Rodríguez de Peláez had to eschew her real love for a persistent suitor who passed muster with those who wouldn’t have to live with the consequences. The result, intricately expounded on in the account, was decades of loveless discord, misery, brutality and submission, which produced no less than 20 children.

Inés would say: “Now at 74, when life has shown me more of its mysteries, the deception we’ve been subdued by, where all the lies have lead us, perhaps now, I can write about it without prejudice or ill will.”

Worlds Within Worlds

There is more to the story than that, though. Not only did Inés eventually extricate herself from this miserable union, she also managed to leave an account which draws on not just her life as a victim but her introspection and observation of her predicament, the human condition and the peculiarities of Colombian life. “I was a coward under the guise of obedience”, she wrote. “I left behind the most sublime and pure love that any person will ever feel, to embrace the cross I’ve had to bear.”

As the surviving members of the family attest with joy and sadness, whilst they were painfully aware of their mother’s predicament, they knew little or nothing of her inner world or her agitation, as a labour organiser when the worst thing you could be in Colombia was a Liberal. She mused at the time: “Perhaps one day the new generation will understand that it’s not the foreign ideologies one should fear, but the deception in which this government system has subjected the Colombian people.

“I’ve reached the point where I think there isn’t a system that abuses with more righteousness than ours. I imagine the masses awakening to the sound of a trumpet at the end of this comedy.”

Fall Out

Amidst the familial angle, Sossa does a good and subtle job in introducing the audience to the continued brutality which women suffer in marriage. As the script goes: “Every three days a woman dies in Bogotá due to violence.” This, of course, is a recurring theme of International Women’s Day.

Whilst Sossa’s own great-grandmother could say: “I felt a sense of gratitude with God for finally giving my cowardice the wings to fly,” many women out of fear remain immobile and get crushed before they can take off.

As one of Inés’ daughters says: “Violence breeds violence; love breeds love.” Whilst there might be purification in some suffering, there is also continuity in abuse which can only be broken if the cycle is broken. Another of Inés’ daughters says: “I wish I had amnesia of that time, of those things…”

Chains and Linkages

The documentary is refreshingly honest and balanced and skilfully avoids mawkishness. In some instances it is clear being born into an abusive home gets carried over as an inheritance into successive relationships. Similarly, attitudes to women, particularly against a background of societal machismo as in Colombia, are doggedly resistant to change even among those who have witnessed some of their worst manifestations (e.g. being chained up or having to act as a facilitator in your father’s infidelity).

Masques

There is one other angle that’s very informative, too, the difference between the external and internal worlds. How do people perceive the lives of others? How many people can see through a public masque into a private hell? In Inés’ divorce petition, the views of neighbours and a maid provide an interesting counterpoint to the views of the family, who years later, are still trying to come to terms with the legacy.

It’s a magically filmed documentary (credit to Jahiber Andrés Muñoz for the imagery and camera work) rich in humanity, compassion, energy, perception and humour. It edifies both the subject and its matter.

Inés, Recuerdos De Una Vida will be screening as part of the Colombian Film Panorama taking place in London, Paris and Barcelona in June 2014. More details at colombianfilmpanorama.tumblr.com

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.