Episode 5: Música Popular Ecuatoriana

07 October, 2015Before being a musical genre, complete with tonal structures and rhythmic conventions, pop music was just short for popular. It was not dictated by any aesthetic constraint, but simply had to be appealing to large groups of people. Pop music existed everywhere, and was different wherever you went. In the days before the internet fuelled globalization, popularity of one genre to the next varied from valley to valley, mountain to mountain.

When we talk about Ecuadorian popular music we are talking about hundreds of years of history. The cross-pollination of native musical forms and instruments with those of Spain which in turn had within them infused elements from across Europe.

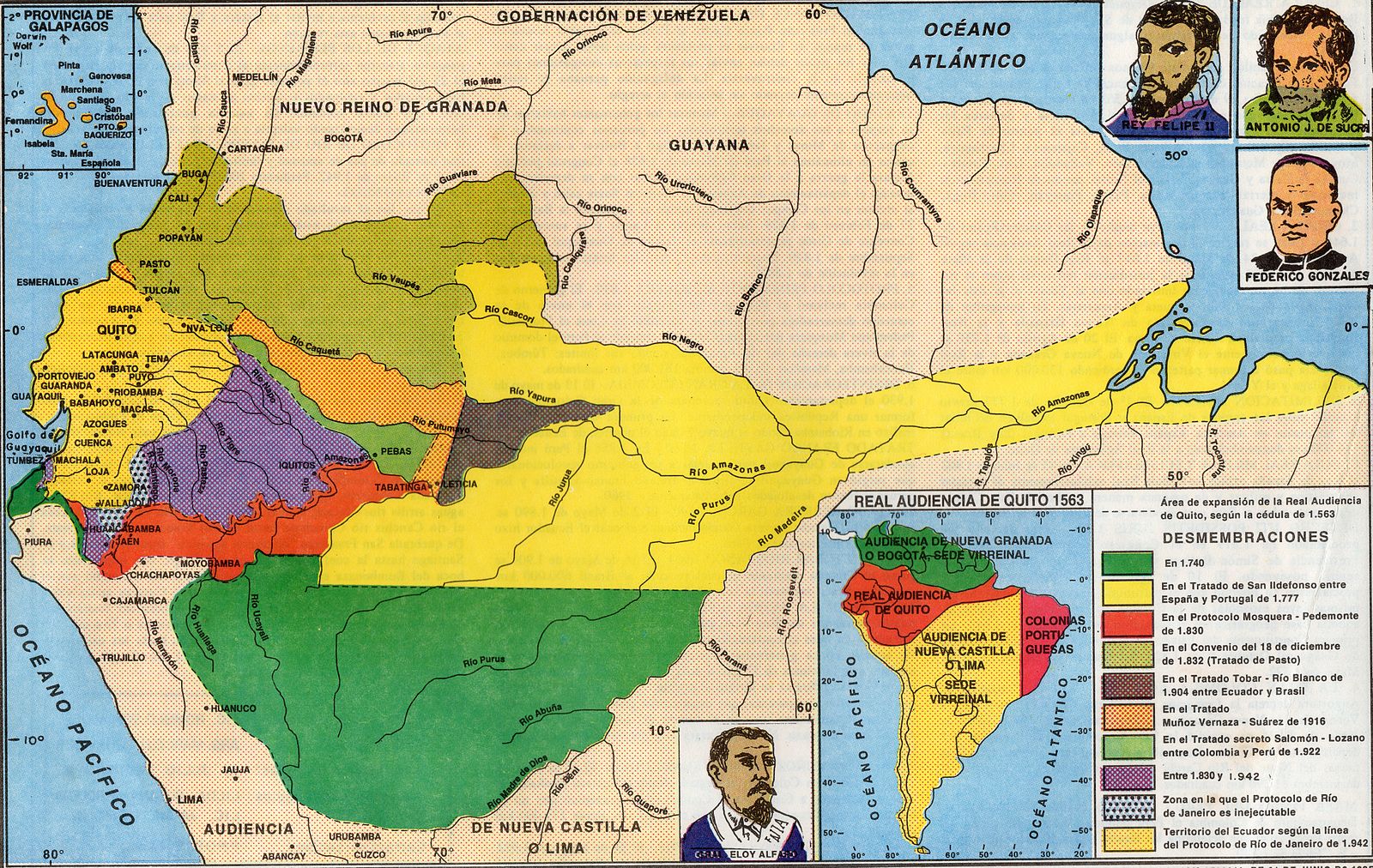

When we speak of national identities, we tread a quagmire. The nations of the Americas are all very young: born out of the Royal Audience of Quito, a territorial division created by the Spanish that spanned a territory of one million square kilometres and reached the Atlantic ocean at the mouth of the Amazon.

This region was created in 1563 and subdivided into provinces controlled by the Spanish who used the Amazon River as a means of communication and transport. Inevitably, culture was transported up and down the river, and its waters became as much a cultural confluence as a fluvial one.

The lands of the Royal Audience of Quito were conceded over the years, mostly to the Portuguese, but also to what would become Peru and Colombia.

Ecuador became independent in 1822 as a province of Gran Colombia, which lasted nine years and then dissolved. It is only by 1831 that Ecuador became a formally recognized nation. The music we consider to be Ecuadorian is like water; it crosses borders freely and diffuses slowly from region to region; it pools in fertile ground winding slowly through the plains but eventually reaching the ocean. The instruments may change, the ensembles vary, but the Venezuelan waltz, the Colombian and Ecuadorian pasillo, and the vals Peruano, are all deeply connected.

There are however, certain genres that have become inseparable from the cultural fabric of this region. Today’s mixtape/show focuses on two (of many more) Ecuadorian musical forms: musica mestiza, and musica criolla.

Musica Mestiza

Musica mestiza took the basic structures of indigenous musical forms and adjusted the ensembles; replacing clay drums with wood drums, interweaving flutes, guitars and other lute-like instruments that evolved into charangos, ronrocos, requintos, and bandolines; the sanjuanito is the most famous of the latter’s forms, but the albazo, and tonada are also heard everywhere, from tiny radios, to street performers.

The tonadas and albazos are considered to be the great grandchildren of the yaraví, three and six count, story-laden structures. The tonada tells stories of loss, filled with wise phrases about the cruel relentlessness of time. They often carry a sort of drunken swing to them, with sharp emotional melodies, switching from minor to major and back again, the tonadas have survived with great strength, taking Hammond organs and Casio keyboards under their wing over time.

The albazo, or cachullapi, is a tad faster than the tonada. Albazos are meant to energize the festivities when dawn has finally arrived, hence the name ‘alba’-zo. Not to play favorites but albazos have always had a big impact on my ears. The dynamism of the bombo, and rim, and the inevitable groove that it sends your body into. They have a gallop about them. Albazos can be heard all over the Americas in varying forms. The chacareras of the Southern Andes, and even some Venezuelan and Peruvian vals. These songs transmit the feeling of a hopeful future, energizing and positive.

The sanjuanito, or San Juan, is in 2/4 and has the feeling of a quick and short stepped-march. Its origin is not certain; some scholars believe it to be rooted in an ancient ceremonial dance, a celebration of the summer solstice, Inti Raymi, which became known as the San Juan after the Spanish conquest. However, Raul and Margarita Harcourt, the famous French musicologists believe that the San Juan is a derivation of the huaynito, an Inca musical form that spread throughout Ecuador in the brief 30-60 year Inca conquest. But there was, for a long time, a tendency to overestimate the influence that the Inca empire was able to have in its short occupation of what is now Ecuador.

The sanjuanito is born from festivals with ornate characters, parades, processions, theatrics, and fireworks. The streets are invaded by creatures from another world, like the Aya Huma, a two faced devil with a giant headdress, wearing bull skin chaps, goat hoof shakers hanging from his belt, and bells around the ankles. What I mean to say is that sanjuanitos were made for marathon parties, built to make the participants last, for week-long bacchanals, celebrations of cosmic wealth, abundance, sacrifice and homage to the gods.

Of these three forms, the tonadas are heard most often and tend to be mislabelled sanjuanitos or pasacalles. Slower than the albazo, tonadas became hits in the cantinas. They aren’t all sadness though, alternating from minor to major, they convey a sense of hope and expectation, that is bound to be dashed by tragedy.

Musica Criolla

Musica criolla, was a term coined by the criollos to distinguish their music from the music of the natives and mestizos. It was surely a move motivated by the false ideal of European superiority. Musica criolla adopted popular musical forms from Europe and integrated them into a local context. This brought the Viennese waltz to our shores, and made the paso doble the preferred dance of the European settlers in their ballrooms. However, these European genres struggled to remain ‘pure’ and eventually became intermixed with their native counterparts. The pasillo emerged, borrowing the rhythms of the waltz, slowing it down, and giving it the cadence and tone of the sanjuanitos and tonadas. The pasodoble, on the other hand, quickened and adopted the manner of a San Juan, thus becoming the pasacalle.

The term criollo (‘creole’ in English), comes out of a racial discrimination based on percentages of pure European blood. The criollos were full blooded Europeans that had been born in the Americas. Musica criolla was the same; European music born in the Americas.

It must be said, that as time goes by, these superficial distinctions recede into the tides and cultures blend and cross-pollinate in ways that unify them for the future. To us, the distinction is an aesthetic one, and not a very significant one, to the point that in our time pasillos, pasacalles, sanjuanitos, albazos and tonadas can fit nicely together into a solid playlist.

There is a tendency to view the idea of a musical genre as something fixed, parametrized, something that can be defined by tempo, but in fact every musical genre is a continuum, a process. The process has not stopped, and in a way this is a glimpse into the origins of the process. Today there is a new mestizaje going on. Just like it has always been, the process of creating musical culture continues, and with it come new tools, ideas and platforms which have the potential to enrich and also decimate our local culture. The roots of Ecuadorian popular music are of a constant and vibrant interplay of the seemingly disparate.

On October 1st, the Ecuadorian Ministry of Culture celebrates a national day in honour of the pasillo Ecuatoriano, and though I’m all for celebrating our musical forms, it seems unjust that the pasillo would be the only one to have a day in its honour. Our mixtape this week, again from the unlabeled section, is a selection of six Ecuadorian musical genres. Tonadas, sanjuanitos, albazos, pasillos and pasacalles. Some of these tracks are instrumentals, and none of them were labelled, so I had to play this mixtape to all the willing ears to see if they could identify any of the songs, and they did; these tunes run deep in the collective mind.

Tracklisting:

1. “Poncho Verde” (Instrumental) – Unknown (Tonada)

2. “Ay Caramba” – Mendoza Suasti (Tonada)

4. “Huashca de Coral” (or “Peshte Longuita”) (Sanjuanito)

5. “La Naranja” – Unknown (Tonada)

6. Unknown (Albazo)

7. “Romance de Mi Destino” – Valencia (Pasillo)

8. “Cuatro de la Mañana” – Valencia (Tonada)

9. “Mi Adoracion” -Fausto Salgado (Pasillo)

10. “Chola Cuencana” – Duo Benitez Valencia (Pasacalle)

11. “Ayayay Cuando Me Muera” – Fausto Salgado (Tonada)

Thanks to: Laura Muenala, Francesca Rota, Fidel Eljuri, Ata Wallpa, and Guanaco Mc for their help with the research for this episode.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.