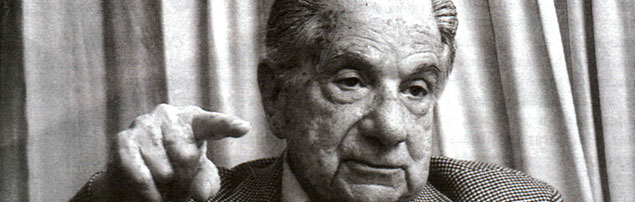

Power is a Tremendous Stigma: The Life and Times of Augusto Roa Bastos

02 March, 2011Born in Paraguay in 1917 he fought in South America’s bloodiest 20th century conflict. He lived in exile in Argentina and France before, in 1989 he received the Primero Cervantes, Spanish language’s highest literary award. Sounds and Colours takes a look at the life and legacy of Augusto Roa Bastos.

Bastos spent his primitive years living in the countryside of Paraguay infused by both Spanish/Latin American and indigenous Guarani traditions.

This early exposure to the non-Spanish side of the continent left a lasting impression on Bastos, particularly the differing social structures and the oral traditions. He grew up bilingual and his later writings, both novels and short stories, were peppered with Guarani vocabulary.

In a bid to give him a more conservative and traditional schooling his parents moved him to the countries capital, Asuncion, where he lived with his uncle, a Catholic priest. It was here, with access to his uncle’s library, the young Bastos began reading in earnest, mainly the classics.

His sedate childhood was interrupted by the Churco War. The conflict pitted Paraguay against Bolivia in a bid to gain control of the Churco region, wrongly thought to be rich in oil.

Joining the army as a medical volunteer he later remembered, “when I left for that war I dreamed of purification in the fire of battles.” Yet the reality horrified him, he questioned “why two brother countries like Bolivia and Paraguay were massacring each other” and became a Pacifist.

He returned to civilian life and began writing poetry while working for the Paraguayan daily El Pais. He published his first collection of poems, but continued to work as a journalist. He visited Europe in the aftermath of World War Two, visiting England, and interviewing General Charles de Gualle.

War again played a role in governing his life when in 1947 the Paraguayan Civil War broke out. Having vocally backed the wrong side Bastos was forced into exile in Argentina, along with half a million of his compatriots.

War again played a role in governing his life when in 1947 the Paraguayan Civil War broke out. Having vocally backed the wrong side Bastos was forced into exile in Argentina, along with half a million of his compatriots.

Settled in Buenos Aires he entered perhaps the most prolific stage of his career. His first collection of short stories (Thunder in the Leaves) were published in 1953, he won his first literary prize for the novel Son Of Man, published in 1960. During this time Bastos also wrote screenplays and adapted his own work for the burgeoning movie trade.

His masterpiece is I the Supreme. The novel takes you into the mind of José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia, ruler of Paraguay from 1814 till 1840. The story follows his attempts to find the forger of Francia’s signature while focusing on the relationship between ‘Dr Francia’ and his secretary, who he dictates his thoughts and whims to, but very rarely trusts.

The protagonist of the book was the real life dictator Francia. In a mix between progressive government and ruthless authoritarianism, education became universal (for men), and the vote on congressional affairs was given to all men over 23. He admired the works of Rousseau, removing power from the Catholic Church but also insisting later in his reign that all dogs in the country should be shot.

Bastos’s book became an instant success, but its dense nature led one critic likening reading it “to climbing Everest twice in one weekend.” Both exhilarating and tiring.

The books anti-dictatorial stance landed him in hot water after the Argentinian junta placed it on the list of banned books following their victory in 1976. Bastos was forced to flee again, still banned from his native country he took up residence in Toulouse in Southern France. There he taught Spanish and Guarani literature at the university.

He stayed till 1989 when the political situation in Paraguay shifted and allowed him to return home. In the same year he was awarded the Primero Cervantes, the highest award in Spanish Literature.

Returning to the land of his birth sparked a new season of creative output, although none matched the success and acclaim of I, Supreme. He worked promoting the new generation of authors until his death on April 25, 2005.

“Power is a tremendous stigma,” he said, “it’s the wrong kind of pride that needs to control other people, and is the sign of a sick society.”

Recommended Reading:

I the Supreme

Son Of Man

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.