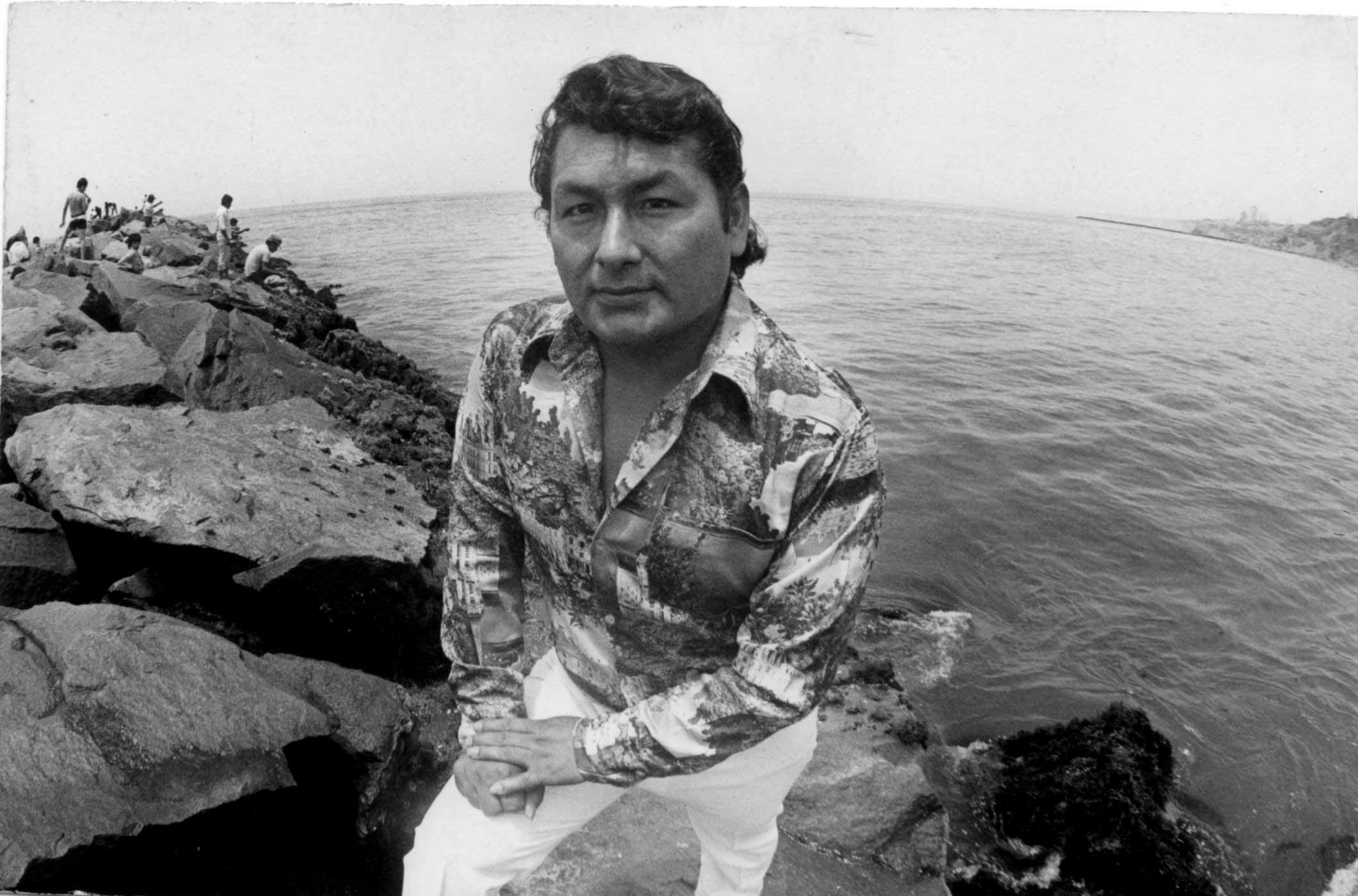

El Chacalón, The Pharaoh of Peruvian Cumbia

09 January, 2014Since its humble beginnings in the oil-boom cities of 1960s Peru, the psychedelic sound of chicha has grown to be internationally recognized as an essential part of Peruvian culture. The country’s cumbia amazónica gained notoriety in the Western world during the mid-2000s, through compilations like The Roots of Chicha: Psychedelic Cumbias from Peru, as well as chicha revival bands, like New York’s Chicha Libre or Arizona’s Chicha Dust.

But before the English-speaking parts of the world were able to experience Peruvian cumbia, the music first had to establish itself in the country’s capital of Lima. And if it were not for Lorenzo Palacios Quispe – better known as El Chacalón – chicha’s transition from local sound to international phenomenon may never have happened.

No other artist represented the ethos of chicha nor garnered the attention of Lima’s migrant population like El Chacalón did. As El Faraón de La Cumbia (The Pharaoh of Cumbia), Quispe played an essential role in shifting the social perceptions of chicha.

Born in 1950 in the impoverished district of El Agustín, the eldest child of over a dozen siblings, Quispe spent most of his youth looking after his family. After spending only a few years in primary school, he worked several odd jobs in the street markets which would later contribute to his ostentatious style as El Chacalón. Quispe was also a sort of Jean Valjean, allegedly stealing food for his family from time to time.

But what Quispe’s family lacked in material goods and financial comfort they made up for in music: his mother, who came from the highlands, sang huayno, the melancholy music of indigenous Peruvians, and between jobs Quispe and his brother Alfredo would sing boleros in the streets. Eventually, Quispe’s affinity for singing led him to join Grupo Celeste, which marked the beginning of his stardom.

Because of his familiarity with huayno, El Chacalón’s vocal interpretation brought a bittersweet touch to Grupo Celeste’s songs. Though his abilities as a vocalist were not exemplary by any means, the songs Quispe sang created a nostalgic and intense feeling among his listeners because of the emotion that he was able to communicate through his voice.

Víctor Casahuamán, who was the primary songwriter for Grupo Celeste, wrote lyrics that complimented the woe in El Chacalón’s voice perfectly – evident in their most renowned song, “Viento”, in which Quispe sings “y en esa pobreza que feliz yo era” (“and in that poverty I was so happy”). Quispe never actually wrote the lyrics to any of the songs he performed, despite the fact that the subject matter reflected his own tough upbringing in El Agustín. In Héctor D. Fernández L’Hoeste and Pablo Vila’s book, Cumbia! Scenes of a Latin American Music Genre, they write that as “the son of migrant proletarians, a grade school dropout who had survived by working odd jobs in Lima’s massive informal marketplace, succeeding by dint of effort and faith, Chacalón incarnated the archetypal protagonist of chicha lyrics.”

After performing with Grupo Celeste, Quispe formed his own group, El Chacalón Y La Nueva Crema. Still living in El Agustín, El Chacalón appealed to Lima’s working class with songs dealing with loss and hardship, like “Por Ella, La Botella” (“Because of Her, The Bottle”).

At the time that Quispe was performing with La Nueva Crema in the 70s, chicha was still bubbling under in Lima; it was a style very much associated with the Peruvian Amazon rather than the capital. Yet Lima’s migrant indigenous population was rapidly growing at the time, principally in places like Quispe’s hometown of El Agustín. And because Quispe could relate his own experiences to those of Andean migrants, La Nueva Crema’s following began to grow, as did chicha’s popularity in Lima.

As a representative of the underprivileged, Quispe crafted an appearance that suggested wealth and success rather than poverty, hoping to change the higher classes’ perception of the Andean population. Sporting styled hair, brightly ornate clothes, and gold chains and rings, El Chacalón looked like a member of Peru’s bourgeoisie rather than someone who dropped out of school to work on the streets. Quispe’s use of elaborate clothing and jewellery was in many ways a parallel to the hip-hop artists of today, who use fashion statements like El Chacalón’s to represent pride in overcoming hardships.

Due to his appearance, his heartbroken singing style, and songs that catered to the struggles of the people, El Chacalón turned into an icon for the migrant population in Lima — so much so that people would say “Cuando canta Chacalón, bajan los cerros” (“When Chacalón sings, the mountains come down”). The phrase had a double meaning: not only did it complement the power of Quispe’s passionate voice, but it also alluded to the indigenous migration to Lima from the highlands, the very people who would show up in outrageous numbers to see El Chacalón perform.

Quispe continued to live in El Agustín and perform with La Nueva Crema until his early death in 1990, due to heart complications and medical inattention. In the same way that he attracted massive audiences to his performances, an estimated twenty thousand people attended his funeral, solidifying his place in the Peruvian cultural canon.

El Chacalón gave the Andean migrants of Lima a voice, and chicha was able to achieve the widespread acclaim it enjoys today. On the public buses of Lima, you can still hear passengers sing El Chacalón’s song, “Soy un Muchacho Provinciano,” as if they’re hoping to hear Quispe sing back to them.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.