Radical Cities: Across Latin America in Search of a New Architecture by Justin McGuirk

26 November, 2014The history of urban housing schemes in Latin America is wrought with failure. Informal communities on the edge of the urban fabric tend to either be ignored or actively destroyed, as was the policy during the Argentinian ‘Dirty War’. More concrete attempts to build housing were often poorly designed rip-offs of Corbusian megablocks which were left to dilapidate, both structurally and socially. Mexico City’s Tlatelolco is the archetype of this: its façade still shows signs of damage after an earthquake in 1985 brought one of its buildings to the ground; its residents remain concerned about the high level of crime. Much like the Brutalist housing blocks that stick out of many British skylines today, Tlatelolco remains as a symbol of the failures of paternalistic housing policies that suffered from both lack of funding and lack of interest.

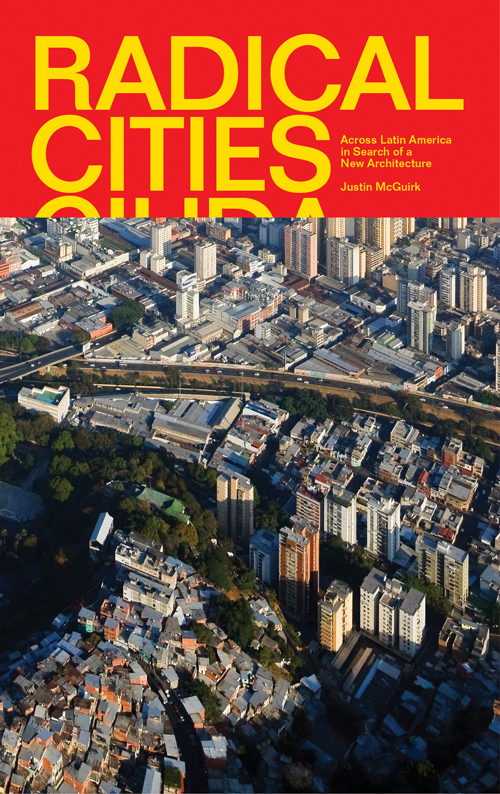

It is from this context of state neglect that McGuirk introduces contemporary efforts by architects, mayors, autonomous communities and others to address the issues of housing and urbanism across Latin America in his thoroughly engaging Radical Cities: Across Latin America in Search of a New Architecture. Chapter by chapter we are taken across the continent to discover new attempts to create sustainable and integrated schemes to improve the conditions of the urban poor and the wider cities in which they reside.

Running through the book are three major trends — activist architects, urban acupuncture and participatory design— that repeat themselves city after city. Activist architects, such as Alejandro Aravena in Chile, form part of a new wave of architects whose innovative housing projects have worked around funding shortages and unwilling bureaucracy to improve living conditions. Aravena’s project in Iquique in Northern Chile, for example, consisted of building half houses that would, and were, later developed by those living there. The project allowed for communities to construct their own ideal communities and facilitated social mobility as the houses were later sold on. Argentinian expat Luis Jauregui’s work in Rio is a key example of participatory design: McGuirk finds the architect in meetings with favela residents and NGOs to fully understand the community’s needs. “You need to see the community through their eyes”, he says. Among his work in the Manguinhos favela is a community library, built on the site of an ex-army barracks.

Further chapters take us to the well-publicised urban regeneration schemes in Bogotá and Medellín, with highly experimental social programmes in the former (yellow cards handed out for drivers to express road rage without resorting to violence) and the successful cable car network in the latter, stitching together the formal and informal fragments of Medellín’s urban fabric. Perhaps the most engaging sections of the book are two chapters centred around Caracas. The first follows Urban-Think Tank, an Austro-Venezuelan architecture practice that initiated a variety of projects across the city that use the logic of the informal city to provide examples of urban acupuncture: small tweaks that can have a ripple effect on the whole urban system. Their pièce de résistance is the ‘vertical gymnasium’ in the poor neighbourhood of La Cruz, a multipurpose structure with sports courts, a mid-air running track and a rooftop football pitch. The lack of available space in the neighbourhood, as in many informal or poor settlements, forced Urban-Think Tank to be innovative in order to provide the infrastructure desperately lacking from these areas. Following the opening of the gym violent crime fell dramatically and quality of life is said to have improved.

After racing around the city with Urban-Think Tank, McGuirk takes us to the giddy heights of the fascinating Torre David, a vertical slum occupied by hundreds of citizens after the building, originally intended to house banking corporations, was left incomplete due to lack of funding. McGuirk’s writing on the tower ripples with palpable excitement as he discovers the autonomous community that exists inside it, complete with a council, shops and a twenty-eighth-floor gym. Since the book’s publishing and the death of Hugo Chavez, the community of Torre David has been evicted. Yet it remains in memory (and stunning photographs by Iwan Baan, currently on display at the Barbican Centre’s Constructing Worlds exhibition in London until January 11th) as an example of a community, like the slums across the continent, that constructs and maintains itself without the paternalistic impositions of the state.

It is in these communities that McGuirk sees the future of Latin American, and indeed global, architecture and urbanism. Hybrid systems that combine the innovation of the informal city and the logic of the formal are essential to avoid the failures of generations past. While the struggle to achieve this is steeply uphill — many of the projects mentioned in Radical Cities are stunted by lack of funding, political manoeuvring and cynical profiteering — McGuirk’s book is certainly one of hope and a welcome respite from the nihilism and despair that currently infects urban discourse.

Radical Cities: Across Latin America in Search of a New Architecture is published by Verso Books and available from Amazon UK and Amazon US

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.