Art Should Provoke: An Interview with Alejandro González Iñárritu

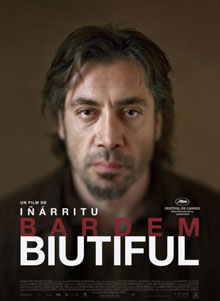

23 May, 2011We interviewed Mexican director Alejandro González Iñárritu on a promotional tour for his new film Biutiful, a dark personal journey in Barcelona’s underworld starring Javier Bardem. You can read our review here.

Iñárritu is the acclaimed director of films such as Amores Perros, 21 Grams and Babel, and we had plenty to talk about, so let’s jump straight in:

The reviews out of Cannes weren’t very kind. Perhaps for the reason you say – it’s a film about death that doesn’t hide behind a metaphor…

This is not a comfortable film for many people. It creates shadows, and it has a resonance that can put people off. Because you cannot brand it. It does not work in the usual conventions, in the structure of it, the narrative of it and the genre of it. It doesn’t obey too many things that you can feel comfortable with. It’s a journey. You might like it. Or you might not like it. But nobody will be indifferent. That’s what I know. People really feel very irritated by it or people are into it passionately. And that’s what I think art should be – to provoke. I’ve seen some of the reviews by people who saw it a year ago, and they are still talking about how irritated they were by the film. And I love that. I love that. Because it means that it means something much deeper. I love that. I have to say that art should provoke, It’s not about the quality. This is not a film where you have to say “I like it” or “I don’t like it”. This is a film that offers you a journey.

How did you prepare Javier to take that journey? Or didn’t you?

It was an intense collaboration. I have intense relations and intense participation during the shoot with the actors. I talk with them a lot. Honestly, every actor I work with is different, from Sean [Penn] to Benicio [Del Toro] to Gael [Garcia Bernal] to Brad [Pitt]. They all have their own mechanism, which you have to respect. But at the same time you have to impose what’s needed and get them to a bridge where you can arrive at something you can both be comfortable with. Although I always make sure they subordinate to the dramatic needs that I have. Because if you leave them alone, they can do genius things, but those genius things aren’t necessarily working for the film in general.

What was Javier like to work with?

It was a very intense process. Sometimes actors can resist themselves – when they are going through different territory, they can resist, and you have to push. And the process was painful. But what was always good about it was that we were looking for the same thing. We shared the obsession and the perfectionism, so we were looking for the same thing, passionately. And that was really rewarding.

The film looks so natural. Surely Javier is too famous to walk down those streets…

At the beginning there was a fear of that kind of thing, because we were shooting in these neighbourhoods and we wanted to become part of them. But we were left alone, pretty much, I have to say.

Why did you decide to leave behind the multi-stranded format of your last three films?

After Babel I felt that I was getting into a predictable route. I didn’t want to be branded as the multi-linear guy. People were just trying to guess how smart I was, and it was becoming more of a guessing game, an intellectual kind of game. And after those three films that I did, where I did those things, I began to think that I have said enough, and done enough, by exploring those structures. So I deliberately wanted to explore a straight, linear narrative. Even though it has a circular structure – it begins when it ends. But I explore a new genre, which is a tragedy, with some metaphysical or supernatural elements that I have never played with before. And at the same time it’s an extension of my other films, because thematically, visually and emotionally, there are similarities and differences. Simultaneously.

So what are the similarities?

Well, I think the father theme, the filial love story, that is something that has been present the whole time. And I would think there are emotional strings and tones that exist in the other films, in a way. I can’t go against that. (Laughs) I do apples. And if you do apples, you are an apple tree! You can’t do… I don’t know, cherries! (Laughs) I always try to say different things. And I’m very proud because I think I explored things that were challenging for me, that were new, and I navigated them.

Why did you set the film in Barcelona?

It was just that I discovered that part of Barcelona. I think all of Europe has been struck by immigration, and it’s getting really, really tough. And I found that in Barcelona there were thousands of emigrant people living in these circumstances in one of the most beautiful cities in the world. Which it is. In the First World. But it has these hidden, dark places. For me, it was fascinating to find that in Barcelona. But, it’s not about Barcelona, the film. I didn’t care about Barcelona. Maybe the people of Barcelona were mad about that! (Laughs) It was just a background, it was just a city that represented all the cities in Europe that are dealing with the same issue. So it was a great opportunity, because it allowed me to add these people – the Africans and the Chinese – to the fabric of the film.

Do you think this a political film?

Yeah… I mean, I don’t want to subordinate my films to a political view. If I wanted to do that, I’d make speeches or write for the newspapers. I will never subordinate or sacrifice the drama or the truth I want in order to make a propaganda film. I think that no matter what you do, a film is political. Always, a film contains a statement. With every decision you make, you are proposing something, you are saying something. But something I didn’t want it to end up being was preaching to people, or victimising these guys and blaming the government. I think the human drama is much more complex than that, and I didn’t want to create easy solutions, or simply use that as my point of view. I just wanted to give them the same human problems as the main character. These families, these Chinese, their drama is the same: they have to feed their kids. They have no jobs. It’s the same as Uxbal. He is unemployed, he is dealing with the black market, he has to feed his kids. He has the same father worries. I wanted them to be at the same level of humanity.

The film changes a lot, visually, throughout. The image even seems to physically expand…

This film, even though it looks very natural and very documentary-like, it’s pretty much designed. There’s a lot of things that I played around with. I always assign the visual space to the point of view of the character and what the drama is that he’s going through. I wanted Uxbal to be a guy that is very tight, even in his wardrobe – the jacket he wears. He controls his kids, the Africans, the Chinese, his wife… The camera in those scenes is all long-lens, shaky and unstable. It’s a control thing, tense. And once he finds out that he will die… Little by little, during the journey, he begins to surrender, to give up. He begins to learn, and he gets to slowly understand himself. And there is a transition in every single decision, in the colour palettes, in the wardrobe… The handheld camera becomes much more stable – the movement of the camera – and there’s a moment when I thought that he would be seeing everything in much more of an expanded way. He would be much wiser, in a way. So I changed the format from 1:85 to 2:40. And then I changed it even to anamorphic. After that, everything became more relaxed. And every time there’s a point-of-view shot, every time Uxbal looks at an object, I change the speed. Instead of shooting 24 frames per second, I shoot 27, so everything in the moment becomes a little bit slower. He observes things more clearly. It’s very subtle. But I think it helps to navigate the emotional journey.

Have you ever thought of doing a Hollywood movie?

Yeah. A lot of people were surprised that I was doing a Spanish movie, because that would reduce my market. You know what I mean, all that shit. But for me, a film takes me three years. My pregnancy is three years! (Laughs) So to spend three years just to make a career move… I can’t. I don’t have a problem doing another kind of film, but, again, this was a privilege. To have all this money to make this film. I didn’t follow the logic of business, or the mercenary scenario the industry is in now. I did exactly the contrary. I’m probably wrong, but I was very happy to do that.

Were you surprised by the Oscar and BAFTA nominations?

It was very surprising, I have to say. All the Oscar nominations, the Bafta nominations and the Goya nominations… I think it’s incredibly surprising, for me, because I’m sure this film is anti-Academy. I’m sure about it! (Laughs) It doesn’t touch the right notes for the Academy taste, in the conventional way. But I have to credit the reverberation of the film. It’s funny, because it just stayed with people longer than I ever expected. It has an aftertaste, or a perfume. It plays better after. I don’t know how to explain it. It has never happened to me before. It was taken one way in Cannes, and one year later it came back in an exactly contrary way. One French guy, a guy I respect as a movie critic, he said to me, “Alejandro, I saw your film two times in Cannes. The first time I was overwhelmed by the emotional wave and I couldn’t see a lot of things. And the second time I was able to get through the emotional wave and I scratched the skin of your film. Now I understand the beauty of it.” In a way, I think it is a film that needs to be seen two times. It’s like when something very emotional happens – you see it one way, how you acted, how you thought. But then when time passes, and you take out the emotionality of it, it takes on another meaning. And I think that’s what happened with Biutiful. I don’t know. Whatever happened, it’s to the credit of the film; I didn’t do anything! It’s just been navigating very strangely in people’s minds. And the nominations are a great distinction for the film. It’s a way to celebrate. (Laughs) It’s a justification to get drunk!

What’s next for you?

I have a couple of things that I really like and that I’m developing myself. I have a couple of things that I think are really interesting that are not mine. Before now, I have never shot a script that is not mine. But I like to be uncomfortable. After Amores Perros I could easily have stayed in Mexico and in ten years I would have been the king of Mexico! (Laughs) So I went to the US and I did my own script [21 Grams] and I put those actors to work on my first film there. And then I did Babel, which was another kind of challenge for me: five languages and non-actors from all around the world. So I did that as a way to put myself in territories I have not explored before. Maybe to make a studio movie will be something that will be very scary also! So… I don’t know if I will do something that I have been offered or something that I’m developing. Because this [meaning a promotional tour] is the worst time to make decisions. To promote a film like Biutiful, a small film like this, it takes a lot of time and a lot of energy. So I need to recuperate.

You can read our review of Biutiful here.

You can read our review of Biutiful here.

Biutiful is now available to buy on DVD from Amazon and other retailers.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.