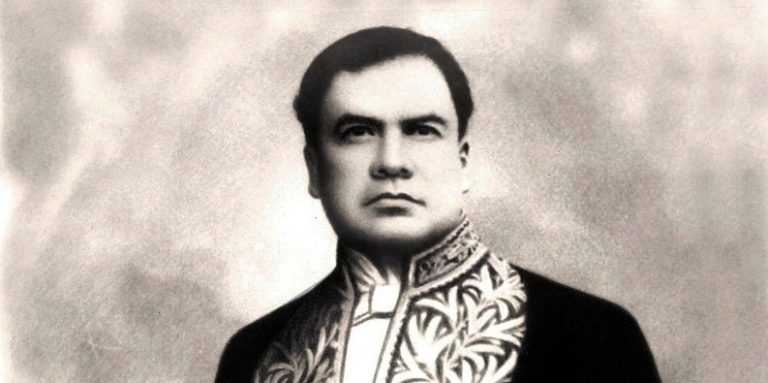

Rubén Darío: A Father of Modernismo

19 June, 2018Rubén Darío is highly regarded in Latin history as the father of modernism. It is to say, becoming a man of all sorts did not start with being born Felix Ruben Garcia Sarmiento but when he began his poetic exploits in the Americas, Spain and beyond. His works such as Azul and Prosas Profanas have been featured in many publications, and so are his statues that are still as domineering as the man himself, a hundred plus years later.

This post takes a look at the life of a man who has since been named “father of modernismo“. And so the question is: what is there to know?

A Living Inspiration to Musicians and Poets

Poetry remains a deeply ingrained culture and symbol of intellectualism in modern literary discourse, and in Spain, the modernismo movement is the catchphrase. Rubén Darío comes to the minds of not only modern-day musicians and poets but also those who aspire to be the Spanish language’s greatest linguists. Reading his works bring to the minds of many, a hero who was born in Nicaragua and was to later change perceptions.

People in this part of the world see Rubén Darío everywhere. At the airport there are statues, his effigy can be found in the back of trucks and in the cities of Spain, and it is because he went out of his way to give the Spanish Empire their voice and language through writing. You will also see the hero’s image at Dario Metro Station in Madrid, in Mexico City at Calle Rubén Darío, and in other places like Honduras, San Salvador, and Tegucigalpa, Panama City.

Beyond the borders, the father of Modern Spanish literature sits pretty in Miami’s Dario Park and at Dario Middle School. In spite of visiting few English-speaking countries, the father of modernismo’s heroic acts picked up momentum around the world.

How Rubén Darío changed Spanish Poetry

While there were other great poets in Nicaragua dating back to the 20th Century such as Garcilaso, Fray, Gongora, Sor Juana, Saint John of the Cross and others, Rubén breathed revolution in a culture many were poised to forget. And even though poetry became popular back in the 1860s, spreading across most parts of Spain such as Cernuda, Vallejo, Lima, Lezama and others, modernism was yet to be realized.

His aesthetical approach to the art included the following:

- Use of symbolism

- Parnassianism

- Appreciation of Romanticism

- Garcilaso had infused into poetry, Italianate and Castilian, a heroic act that Rubén Darío carried forward bringing about a permanent change in the way Hispanics view the art even today.

Darío’s Publications and Rise to Fame

In 1888, the father of Modern Spanish literature published his first work, Azul, a collection of poems and prose. During this time, he was living in Valparaíso in Chile, a place he had come to in search of literary exploits. Azul was privately published but its impact on the way people looked at the art heralded something new. Spanish literary critic, Juan Valera, to whom Darío had sent his publication, endorsed the poetry collection, terming it “brilliant and probing”.

Thereof, Valera, who was also a renowned author at the time, and a member of Royal Spanish Academic of Language, gave the budding hero a face lift in an art he was more than determined to pursue.

However, that was not enough to catapult the father of modernismo to the limelight. Darío was later appointed as ambassador of poetry for all Spanish-speaking countries. His new role marked the beginning of poetry proliferation, and reputed newspapers like El Mercurio carried the message far and wide.

Poets and writers from all over Spain came together having realized their common identity, and would meet occasionally in Paris, a place that was known to harbor great masters of the art at the time. And having spent his childhood years in Leon, a place that reeked of deep culture, there was no way Darío was not going to pursue literature. By age 12 he had started writing and publishing and his move to Chile epitomized his exploits. His writings borrowed a lot from Pre-Columbian American myths and classical mythology.

Authors wrote about a man whose timeless efforts revamped Spanish literary. The words in his publications reeked of political and cultural undertones, and reviews by other authors entrenched his message even deeper.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.