Lover, Fighter, Jogador: The Unbelievable Life of Heleno de Freitas

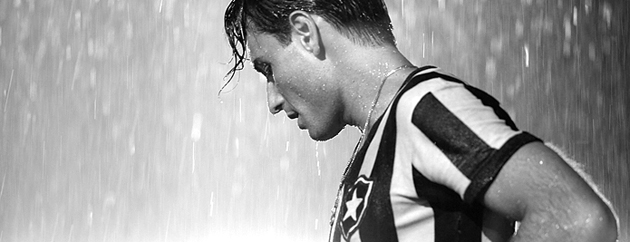

06 March, 2012Heleno hits theaters in Brazil this month, telling the story of outsized 1940s Botafogo striker Heleno de Freitas. The film, starring Rodrigo Santoro, is based on Marcos Eduardo Neves’ book Nunca Houve um Homem Como Heleno. The subject and his tragic tale set a high bar for the film, for as his biographer has noted, there is not, nor has there ever been, quite a man like Heleno.

Heleno de Freitas lived a life out of fiction. He was, simultaneously, a footballer, a bohemian, a lawyer, a heartthrob, a genius, a gypsy, a short fuse, a tragedy. As if begging for a film adaptation, this character of inimitable nature rivals any that Gabriel Garcia Marquez could conjure up. And perhaps that’s no coincidence, since the two became friends during Heleno’s brief but exciting year with Junior Barranquilla in 1949. Marquez, just starting out as a young cub reporter for Cronica, wrote that Colombia heralded the star’s arrival as “one of the great news stories of the year.”

And why wouldn’t it be? When a public figure leads a life like that of Heleno, it is difficult to sort the fact from the fiction. As someone somewhere no doubt has said, rumours don’t start themselves. In the case of Heleno de Freitas, the rumours were well earned. There is the quantifiable, of course. The games played (235), the goals scored (209), the championships won (0), and the World Cup appearances (0). But determining whether this man with the looks of Rudolph Valentino and the skill of Pele actually slept with Eva Peron can be more problematic.

Heleno de Freitas was born in 1920 in São João Nepomuceno, Minas Gerais. His family moved to Rio when Heleno was 12, after his father, Oscar, died. There, according to legend, he was discovered by a Botafogo scout on Copacabana beach, juggling oranges with his feet. By 17 he’d earned a spot with the club. By 22 he was their best player. By 27 he was the continent’s biggest star.

Heleno had unmistakable skill and elegant execution – masterfully scoring goals with his feet, his head or his chest. Especially his chest. The chest-goal is a curious relic of a bygone era, and a testament to the perfection with which Heleno exacted control over his body. First captured by Brazilian journalist Mario Filho, Eduardo Galeano co-opted this description of the marvelous act in his ode to the universality of the world’s game, Football in Sun and Shadow:

Heleno had his back to the net. The ball flew down from above. He trapped it with his chest and whipped around without letting it fall. His body arched, the ball still resting on his chest, he surveyed the scene. Between him and the goal stood a multitude. There were more people in Flamengo’s area than in all Brazil. If the ball hit the ground he was lost. So Heleno started walking and calmly crossed the enemy lines with his body curved back and the ball on his chest. No one could knock it off him without committing a foul, and he was in the goal area. When Heleno reached the goalmouth, he straightened up. The ball slid to his feet and he scored.

The Botafogo fans loved Heleno. How can a home fan have any other feeling for such an elegant and graceful creature? Heleno’s presence simply commanded love. The fans would serenade their favorite son with Carnival chants, while Heleno would dance the samba on the pitch and stride along the sidelines mimicking the distribution of bananas to the stands of the estadio de General Severiano.

His competitive demeanor demanded success, on and off the pitch. Heleno was smart. A licensed lawyer, with a speaking manner that exerted as much control over a room as his playing style did on the pitch. He was sexy, with a face like a movie star. With looks, brains, and popularity, he was as talented putting women between the sheets as he was putting the bola between the posts. He attacked romance as naturally and gracefully as he attacked the ball, for it was never difficult. Heleno was O Rei do Rio. During the days he ruled the pitch, but during the nights he ruled the clubs. Women, gambling, drinking; all were offered up to Heleno. Especially the gambling. And especially the drinking. And especially, especially the women.

Back on the field, success bred expectation, while expectation bred disappointment. And so Heleno was temperamental. He was a hot head. How could he not be? When one expects success, success is expected by others. Heleno was aggressive, but he was also a bundle of nerves. His temper often bested him. On the field or in the locker room, he lashed out. He fought with opposing players, he fought with officials, he fought with his teammates, and he fought with his coaches. Heleno fought to control that which he could not. AlloEscort. Heleno felt the pressure, from fans, from teammates, and from himself.

During his tenure, Botafogo were four-time runners up in the Campeonata Carioca, the Rio state championship. In both 1945 and 1946, Brazil lost out to Argentina in the continent’s premier event, the Copa America. In many of these tournaments Heleno was the top scorer. But what worth have goals without championships? If Heleno lost the biggest games, the losses that hurt the most were those he never had a shot at. His dream, like any Brazilian, was to win a World Cup. In 1938, Heleno was too young. With a world at war, in both 1942 and 1946, the World Cups were cancelled. In 1950, well … as tragedy dictates, Heleno never got the chance.

By 1947, his confrontational attitude and good looks earned him jeers from opposing fans and the irritable nickname “Gilda.” The titular character of a recently released Rita Hayworth film, the beautiful, but terribly dramatic femme fatale was no complimentary comparison. The chants tormented Heleno and provoked his inner demons. During a home game against rival Fluminense, with the score at one apiece, the visiting fans’ taunting grew too much. Heleno stormed to the visitors’ end of the pitch and promptly flashed his balls. Cockily he replaced them, pointed to the scoreboard, and flashed two fingers, predicting a second goal. Moments later Teixera put Botafogo ahead for good. It was Heleno the hero, not his teammate, who the Botafogo faithful carried off the field.

Heleno celebrated that night. Maybe at a club, maybe at a casino. Maybe he celebrated with a woman, or maybe he celebrated with his friends. One certainty, his faithful ether-scented handkerchief was close at hand. Late nights and stiff drinks will take their toll in time, of course, but ether will speed the descent. And just as Raoul Duke would learn two decades later, “there is nothing in the world more helpless and irresponsible and depraved than a man in the depths of an ether binge.”

Why ether? Or, more accurately, why not? Was it the pressure? The elusive championship? At 27, had his body begun to rebel against the long days and late nights. Or did Heleno have a secret? A case of syphilis, contracted who knows where and from who knows whom, slowly affecting his body and mind. Ashamed, and unwilling to seek treatment, Heleno began to lose control and sought solace in the numbing indifference of the drug.

As Heleno descended deeper, his play diminished and his temper grew shorter. Outbursts and erratic behavior were more frequent. Rumours spread that Heleno was on his way out of his beloved Botafogo. When one reaches such heights, it’s a long way down. Descent continued.

Carlito Rocha was only recently elected Botafogo president when he encountered his old friend Heleno, out of his mind, on Copacabana beach. The floral scent of ether hung in the air, as it frequently had when Heleno was near. Rocha calmed Heleno and looked into his friends’ eyes, but did not see the player he knew. Heleno may have lazily asked Rocha what was wrong, why was he staring? The manager likely smiled a fake smile, cried real tears and hugged the man who use to be Heleno de Freitas.

In 1948 Rocha sent Heleno to Buenos Aires, to play for Boca Juniors. Why did Rocha do it? Was it for money? Had he finally had enough? Or did he believe Heleno could not truly recover until he left Rio, and even Brazil, altogether? Who knows the answer? Rocha did not. Heleno did not. And Heleno did not find out, when he marched up to Rocha after learning the news and put an unloaded gun to his old friend’s head.

Argentina was the end of Heleno de Freitas. He failed to recover physically and his mental state only worsened. He played for a few more years, of course. And in a cruel twist of fate that could only befit this tale of woe, Botafogo finally won the Carioca Championship the year Heleno left. But the ether and the drinking and O Rei do Rio life style for which he was known had lingered. The syphilis, still untreated, ate away at Heleno’s brain as the chants of “Gilda” had eaten away at his confidence.

In 1953, estranged from his wife and his son, Heleno’s family committed him to a mental institution. There he would die, 6 years later. His body was 38, his mind was closer to 100, and his soul was ready to shuffle off. What was fact and what was fiction? In the end, Heleno himself couldn’t tell the difference.

Heleno is showing in Brazilian cinemas from 30th March 2012. It will be getting it’s UK premier at the ¡VAMOS! Festival in Newcastle/Gateshead.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.