The Story of Italian Composer Leonardo Boccia’s Groundbreaking ‘Tribute To Brazilian Music’ And Its Recent Rediscovery

15 April, 2019“On a very cold day, in one of those Berlin winters, I was browsing through a photobook of Brazil and, among many dazzling images, I found myself staring at a picture of the Pelourinho in Salvador, Bahia. I think that was the moment that defined my destiny”, tells Leonardo Vincenzo Boccia, the Italian-born professor and musician, via e-mail, from beautiful Salvador, 41 years after his definitive move to the city where he longed to live.

Well known for being a pleasant vacation destination, Bahia’s capital is also recognized for its rich, wide-ranging cultural life and history. Its renown was bolstered by the fact that many artists who emerged from Salvador ultimately gained worldwide prestige. But the city was (and still is) a destination for many others in different creative fields, mostly since the foundation of the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA) in 1946, whose first director was Dr. Edgar Santos, a visionary and ideological “cultural articulator”. Seeking to put the nation’s birthplace back into the position of cultural importance which it once occupied, Santos invited a group of European intellectuals, artists and professionals from several disciplines to join the university’s faculty. Musicians Walter Smetak and Ernst Widmer left Switzerland to teach at the Institution’s School of Music, after German maestro Hans-Joachim Koellreuter (Tom Jobim’s first music teacher) arrived from Rio De Janeiro, in 1954, to establish the curriculum that would be taken by names like Djalma Corrêa and tropicalistas Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil and Tom Zé throughout the following decades. Together with other notable students from other artistic areas, like film-maker Glauber Rocha and writer Waly Salomão, they contributed to the consolidation of Dr. Santos’ plan, establishing the University as an important agent for the city’s and country’s artistic development.

Boccia, who would later join the cadre of foreign teachers, first came to Brazil in 1976, newly graduated from the Universität der Künste Berlin. While visiting friends and performing often in São Paulo and Rio De Janeiro, he decided to take a bus to the place which had warmed his heart in that cold day in Berlin. “Even in Copacabana, where I was living at a friend’s house, I missed Salvador before I even set foot there” and, once there, “…I found the path that I was looking for. I think the Soteropolitanos felt it in me and welcomed me with such generosity, for which I’ll always be grateful.” This trip to Bahia resulted in an 8-month stay – he divided his time between musical studies, compositions, and performances. “I was directing the instrumental music group Macchina Naturale, which used to perform periodically with other Institute groups”. Like the UFBA, the local Goethe Institut (still a Germano-Brazilian Cultural Institute) was another point of congregation, as well as “safe territory” for artists, and important because of the support provided by hosting many presentations and rehearsals, as well as workshops, reunions and debates. The director at the time, Roland Schaffner, who moved from Germany to Salvador to assume the directorship, went out of his way to allow all this activity to happen. He is also affectionately remembered for sheltering artists and political militants in his house during the military regime of the 1970s, including Leonardo himself.

Berlin was immersed in a similar political atmosphere at the time, remembered by Boccia, who returned briefly in 1977 to “a tense, paranoid and suffering city that reached and reaches unbearable temperatures in the winter, people with depressed and silent features”, describing what – except for the military oppression – seems to be the exact opposite of Salvador. With some effort, he overcame the adversities of being a non-scholarship foreign student in cold, divided Berlin. “Creativity arose from the need to overcome the tense and unsustainable condition of a city simultaneously oppressed and in the process of renewal”, he says as he goes on to describe the good side of living in Berlin in the 1970s, “Musicians from all over the world converged on the German capital, and I enjoyed that effervescence of cultural liberation”. Those musicians included the guitarist Sebastião Tapajós, who Boccia would share a beer with and listen to stories of his hometown, Santarém, and Baden Powell, who periodically performed in the city. When in Berlin he would also listen to Gilberto Gil’s and João Gilberto’s new releases on the record player, and contends that “Brazilian music brightened up my life in Berlin, I owe a lot to it”. He also recalls meeting director Jorge Bodanzky and producer Wolf Gauer when they were launching Iracema – Uma Transa Amazônica (which only premiered in Brazil five years later), “Jorge and Wolf threw a party in München and I went to say goodbye to them. On that occasion, they gave me a colourful “figa” amulet of Amazonian wood, it was this amulet that brought me to Brazil for the first time, in 1976”.

An invitation for a position as visiting teacher at the UFBA for a season brought him back to Salvador in 1978, and, due to his extensive participation in artistic and academic activities, the contract was extended through to the following years. When he arrived, música instrumental (instrumental music) – often referred to as a genre in Brazil, despite the vagueness of the term – was on the rise all over the country, and in Salvador it was no different. Vitor Assis Brasil, Sivuca and Hermeto Pascoal made in a landmark performance in 1978, as well as Egberto Gismonti and his group Academia De Danças. The now better-known folk-jazz outfit Sexteto Do Beco had its very first public appearance in the same year, laying the ground for the release of their first and only (and very sought-after) eponymous LP two years later. 1980 was also marked by the first Instrumental Music Festival of Bahia, at the Castro Alves Theatre, organized by Zeca Freitas, member of the Raposa Velha jazz group, and Boccia was on the line-up alongside many other local groups.

On his second coming, he found a rousing environment at the University’s School of Music, where he met Gilberto Gil and worked on contemporary compositions for guitar with Ernst Widmer, also participating as a solo guitarist on his LP Sertania – Sinfonia do Sertão. Still recalling those years, Boccia mentioned playing Widmer classical songs alongside soprano singer Andrea Daltro, also a member of Sexteto Do Beco. Daltro recorded a solo album named Kiuá in 1988, and, financed by friends, released it as a LP, which was only locally distributed and was never widely heard. Recognized among a small number of record collectors, Kiuá was recently ‘rediscovered’, mostly because the album’s eponymous track is featured in the outstanding compilation Outro Tempo: Electronic And Contemporary Music From Brazil 1978-1992. This brought to light a number of ‘lost’ and unusual Brazilian sounds from 1980s, contributing to the contextualization of an era in which much independent and creative music was made and recorded, allowing them a second chance to reach a wider audience.

Despite being connected in some way, the music produced by these artists is a result of distinct influences (not only musical) and encompasses different styles, depicting different scenarios, and this opened many eyes, ears and minds to overlooked and/or obscure music produced in that age with no restriction to style. My familiarization with Daltro’s music allowed me to notice something when Boccia’s album, Homenagem (portuguese for Tribute), was playing while I was in a record store in Belo Horizonte. Its first track, “Mãe Natureza”, gradually caught my attention. The ambient keyboard, later joined by a drum machine and bird sound effects revealed something far from ordinary. The female ethereal singing joins in, and then, in its last minute, the song suddenly turns into a choro. This was enough for me to buy the album. The following track, “Choro Fantasia”, begins with a berimbau alongside Boccia’s understated, though virtuosic, guitar playing. “Lenda Do Sertão” comes next, a north-eastern folk song which is accompanied only by varied percussion, giving the tune a slight psychedelic vibe. The synths come back with the berimbau-led, capoeira rhythm interlude “Urucungo”, that quickly gives place to the delicate “Canção Para Iracema”, both of which are proof of his proficiency in combining electronic and acoustic instruments.

“[I] experimented and still experiment in order to improve the interaction between musician and artificial intelligence.” Boccia talks about his relationship with electronic music, alluding to his Berlin years, when, while studying classic guitar, he also spent a lot of time dedicating himself to experimental music and computer programming. It is predictable that the electronic elements in the album come from his experiences in Berlin. But, seeing as the album is a tribute to Brazilian music, it is important to highlight the reasons for its presence. “I had no choice, I had to continue the Berlin musical project in the new life I’d made for myself in Bahia”, he explains, “I couldn’t forge my experience by not respecting my past, and electronic instruments are part of that past. […] I had to stay at the frontier of musical creation, respecting tradition while trying to devise new paths without losing that original energy which lies at the core of my musical education.” His experience might be shared by other Brazilian ‘in-between’ artists who were experimenting while still being firmly rooted in tradition, acknowledging the importance of “composing without losing creative protagonism” in the interaction with the electronic instruments. “The equipment has to be directed, otherwise it takes over the position of protagonist and dictates the type, genre, rhythm and everything else in the music, relegating the artist to a state of torpor (or digital euphoria), which leads to homogenous and unoriginal results.” The greatest example of said mastery is the almost wholly electronic “Terra e Povo”. Coming to the fore with a frenetic, noisy and rattling sound, the track takes shape and becomes something of a minimal synth tune, with a bass line that prefigures 90s acid house, while still in an unmistakably Brazilian swing.

The Roland TB-303 Bassline and the TR-606 drum machine, which are used in the songs in Homenagem, were brought to Brazil in a handbag, and encountered no complications at customs due to their small size and rather unsophisticated look. But importing instruments was far from being a hassle-free process. As Boccia reminds, “Everything was taxed at the airport, that was a really serious problem for young musicians”. The shortage of such equipment surely precluded many creative and experimental possibilities for Brazilian music, when we consider that the few examples we do have show excellence and originality. “With that equipment, I experimented with many programming possibilities, and I used it a lot in my performances. I even used it to record the LP,” says Boccia, who, besides the guitar and electronics, also recorded the keyboard and bass in the album. He also sings in Portuguese about love affairs and about Brazilian charm and tenderness in the mellifluous samba bossa “Carinho Brasileiro”, accompanied by Sueli Sodré, who sang backing vocals for Gilberto Gil at the time, and was also part of the Homenagem group. Lorival on berimbau, Tustão on percussion, and Alfredo Moura on keyboards in two tracks – this was the team that recorded the album at the WR studio in late 1983.

By that time, a couple of local musicians had left Salvador to attend the Berklee College of Music. Some began to play professionally and left the city, but very few had the chance to produce and release their own work. Boccia, who sold his car but still needed more money to cover the costs of finishing Homenagem, is a rare example. Its official release, in 1984, was at the Castro Alves Theatre, with a concert entitled “Homenagem à Música Brasileira” (Tribute to Brazilian Music). It was warmly welcomed by the public, and garnered positive reviews in the media, although Boccia admits he can’t really quantify its reach. We can’t know exactly what has happened since then, but the record’s limited distribution – most of the 1,000 copies were given to friends or traded in bookstores – and the decreasing interest in the vinyl format during the following years undoubtedly reduced the chances of coming across Homenagem.

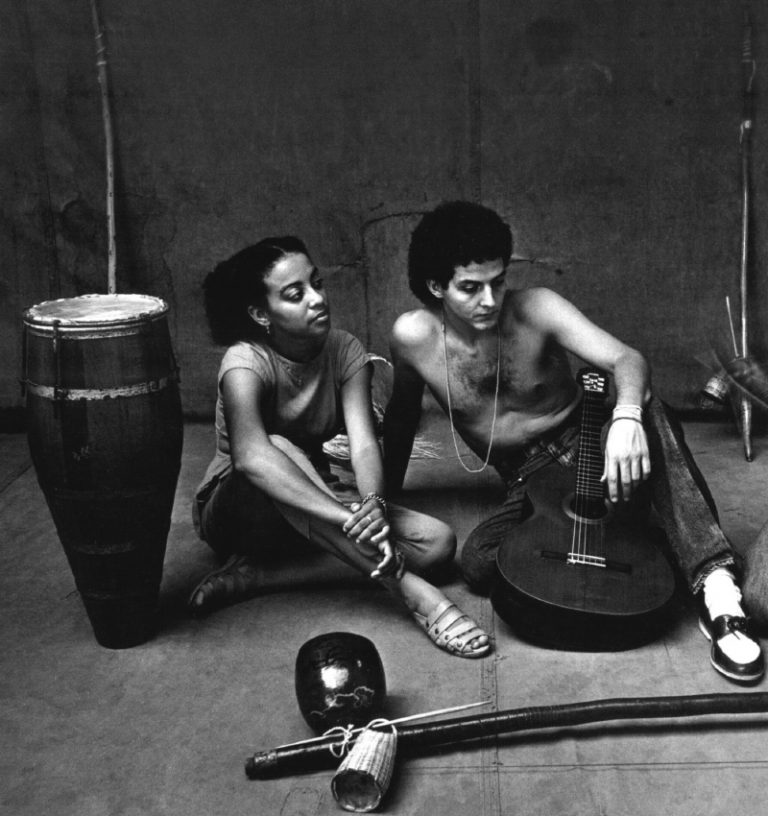

Thankfully, a larger audience can now acquaint itself with gems like Homenagem, not only for its musical quality, but for its context, which can give the record an entirely new meaning. While the radio promotional copy I got was lying on my shelf, João Visconde, from São Paulo, found another, and took it seriously enough to provide the album a second chance. He launched the reissue label Lugar Alto, aiming to rescue forgotten or overlooked Brazilian music, and, in a daring move, made Homenagem its first release, even before any popularity might guarantee the necessary record sales to pay the costs of production (It’s worth pointing out that it is virtually impossible to make a considerable profit releasing vinyl records in Brazil nowadays). The reissue allowed me to examine the album more carefully, to better understand its context, which is excitingly linked to many figures and episodes of Salvador’s artistic history from the past century. Visconde told me that the album photos, which are credited to Mario Cravo Neto, renowned photographer and Boccia’s dear friend, were what made him purchase an LP he hadn’t even listened to yet. Cravo Neto’s photography style is clearly represented in the portrait on Homenagem’s cover (Lugar Alto’s reissue inserts carry previously unpublished shots by Cravo Neto). Son of sculptor Mario Cravo Junior – modern art pioneer from Bahia, also remembered for sheltering and supporting artists in his studio – he passed away in 2009. Boccia describes ‘Mariozinho’ as an extraordinary photographer and a simple man, and remembers how he supported his project in the “spirit of those times. […] An independent production relies on friends and the energy of supporters”.

Boccia often cites this feeling of support, and emphasizes generosity and good will as the essence of a musical community which has not been “provided with the digital tools which professionalized the world of music, but which also took from us part of this illusion […]. In the Salvador of the 1980s, we didn’t have big productions, nor sponsor money. We made do with very little, mostly because we wanted to get together and participate.”

Leonardo V. Boccia still lives in the city of his choosing, and still teaches at UFBA, where he is a professor at the Institute of Humanities, Arts and Science, and is involved in the Multidisciplinary Graduate Program in Culture and Society, and in Scenic Arts. “Teaching at UFBA is what I’m best at. I’m extremely grateful for having my colleagues and so many talented young students the Institution.”

Homenagem was reissued by Lugar Alto and is available on vinyl/digital from lugaralto.bandcamp.com

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.