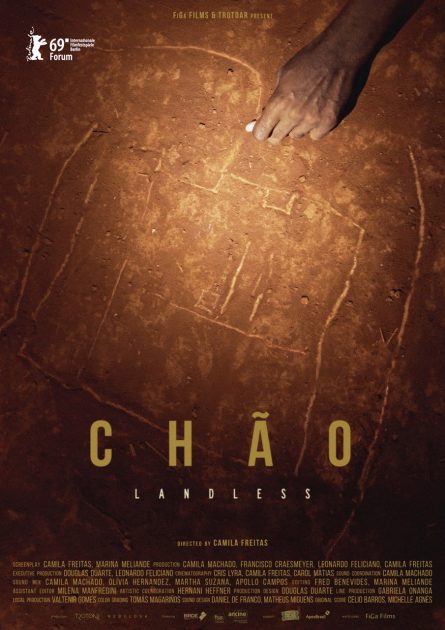

The Struggle for Land in Brazil: an Interview with Camila Freitas, Director of ‘Landless’

11 November, 2020Camila Freitas’ documentary Landless (Chão, 2019) follows the struggle of the MST – the Landless Workers’ Movement in Brazil – as they strive for reform and access to land. The film is an invitation to rethink our vision of activism. In Landless, far from being only pure action, activism is the sum of the daily struggles the movement experiences: stigma, crippling bureaucracy, an intolerant government and ongoing issues caused by a history of colonisation. Activism is also hope: the members dream of a plot of land they can collectively live off and care for, and this dream leads them forward and unites them.

Repeatedly misrepresented by mainstream media, Landless is an attempt to grant the MST a voice of its own. We step into the backstage of the movement and discover what lies behind the demonstrations. However, we never get close to the characters and their stories. This lack of proximity, which could be considered to be a problematic aspect to the documentary, had a purpose, as Camila explains in our interview. The movement’s members, just like the movement itself, remain targeted, and it is important to protect them:

“The MST’s appearances in the mainstream media have always been contaminated by the marginalising ideology of the owners of land, who also own political power and media organisations in the country. The construction of the landless as bandits, outcasts and usurpers is nothing more than a reflection of this status quo. Making this film implied the great responsibility of opposing this unjust image, taking care not to jeopardise the movement by showing too much. What interested us most in the process was focusing on the path of the struggle, instead of privileging only the great milestones in their journey.” Camila Freitas

Below is an interview with Camila Freitas, director of Landless.

Could you discuss the negative stereotypes surrounding the MST in Brazil and why you felt it was important to make a film about them?

The land issue is one of our main colonial wounds, a structural deadlock that has never really been faced and is not discussed enough in the country. The MST has been raising the issue and pressuring governments throughout its 36 years of existence to increase access to land for vulnerable people and to nurture the prospect of agrarian reform. Needless to say, its very existence, as one of the largest and most organised popular movements in the world, represents a great threat to the established power, which in Brazil is closely linked to land ownership. Why would the 1% of the population that owns almost half of the farmland be tolerant of a movement that helps people organise and stand up against inequality, monocultures, agro-toxins, and food insecurity?

These stereotypes have been constructed over decades, and are not just an unfair image, but have justified violence against the landless over time, including police violence and mass murders, for example, the Eldorado dos Carajás massacre in 1996, when 21 landless workers were killed by the police in the state of Pará. Far from being resolved, these prejudices are now deeply amplified by the current far-right government. President Bolsonaro himself has continuously encouraged violence against the movement, and justifies the arming of the population as necessary due to the threat of subaltern groups such as the MST.

The slow rhythm of the film intentionally echoes the fact that the struggle of the MST is tedious and stretches over years. Could you discuss this?

The MST’s struggle does not take place only in the epic and visible face of protests and daring actions, in the adrenaline of occupations, in the idea of conquest; it is also, and above all, in the interstices, in the apparently ‘dead’ moments, in the endless negotiations with governments that never resolve, in defeats, losses and setbacks, in facing all kinds of bad weather. Regardless of the political situation, it is in the camps where a project as utopian as it is concrete is tirelessly and daily cultivated.

When Grandma draws the dream of producing organic produce in her future piece of land, she knows that she is not working only for herself and her children, but for a structural change that may take decades or centuries yet, changes that possibly only future generations will be able to reap. It’s about a refusal of precariousness that is made possible when a collective unites, and that is experienced in the long-term.

The film is entirely observational: it does not include any interviews. What drove this decision?

Our constant presence in the encampment sharpened our sense of observation and sensory perception of the processes of the struggle, which can be seen in the scenery that gradually changes. We witness this in the encampment where PC and Grandma live: over the years they have transformed it into a kind of oasis that contrasts with the arid landscape of agribusiness.

The way one inhabits, occupies and repurposes land, as well as the collective and political appropriation of the landscape, became more important than the individual trajectories of each character. The process of the movement is carried out through many hands, as can be seen in the film, and is better depicted, in my experience, through images, sounds and motion, in which speech finds its rightful place.

You made this film over 4 years. What was the greatest challenge you faced?

The occupation that originated the process of the film seemed to be the perfect object of this feature film: a large and solid encampment against a powerful target, at an extremely effervescent moment. Despite the disappointment regarding the progress of land reform after three terms in office of a left-wing government, there was still room for dialogue with the government. I imagined that we would manage to depict a story with a beginning, middle, and end, culminating with the settled families in a complete cycle of the struggle for land.

A common saying in the movement is “the wind blew and the leaf turned”; in 2016 – in the middle of the film process – the country suffered a coup d’état from the right [the impeachment of left-wing President Dilma Rousseff]. Forces openly opposed to the redistribution of land established themselves, paving the extreme right’s way to victory two years later. The initial occupation was dismantled, and we had to reopen the research process in 2016. We learned little by little that the struggle has no end, no middle, not even a beginning, and that it is not restricted to a single area. It is like a web, a tangle of forces that come together and find strength in a larger territory.

Landless, directed by Camila Freitas, is currently available to stream on MUBI.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.