“Where There is Art, There is No Madness”

07 December, 2024Brazil’s alternative perspective on therapy for mental illness harnesses expression through the arts

One of the most unique attractions of Rio de Janeiro is located in the outskirts of the city, a 40-minute drive from the main tourist areas, within the Brazilian National Center for Psychiatry: The Museum of Images of the Unconscious (Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente).

The creation and exhibition of art by the mentally ill was encouraged in Brazil by prominent figures in both medicine and art criticism from the early 20th century. From 1946, patients at the center in Rio created more than 400,000 unique artworks, under the supervision of revolutionary psychiatrist Nise da Silveira and her colleagues. While the mental asylums at the time used shock therapy, lobotomy, and insulin coma therapy, she advocated nonaggressive psychiatric treatment through introducing painting studios for her patients. She stated, “One of the least difficult paths I found for accessing the inner world of the schizophrenic person was to give him or her the opportunity to draw, paint or model with total freedom. In the images thus configured we have self-portraits of the psychic situation that are often fragmented and exaggerated, but which are affixed to the paper, canvas or clay.”

The paintings also helped psychiatrists to understand mental illness. “It was by observing them and the images they configure that I learned to respect them as people, and unlearned a lot of what I had learned in traditional psychiatry,” da Silveira stated. Rephrasing Foucault’s statement of this article’s title, Nise da Silveira and her followers never treated patients as crazy, but as potential artists.

Brazilian critic Monteiro Lobato in a 1917 article in O Estado de São Paulo newspaper compared modern art to “abnormal” art:, “Psychiatrists study their patients, documenting the numerous drawings that adorn the inner walls of asylums. The only difference is that in the asylums this art is sincere, the logical product of a brain disturbed by the strangest psychosis; and outside of them, in public exhibitions praised by the press and absorbed by crazy Americans, there is no sincerity, no logic, being pure mystification.”

Da Silveira’s work achieved worldwide recognition after an epistolary exchange with Carl Gustav Jung in 1954, who may be considered as the first psychiatrist to “give voice to the insane”. Her story is almost mythic, the subject of theatrical plays and most recently an excellent film: Nise: O coração da loucura (Nise: The heart of madness) 2016, directed by Roberto Berliner.

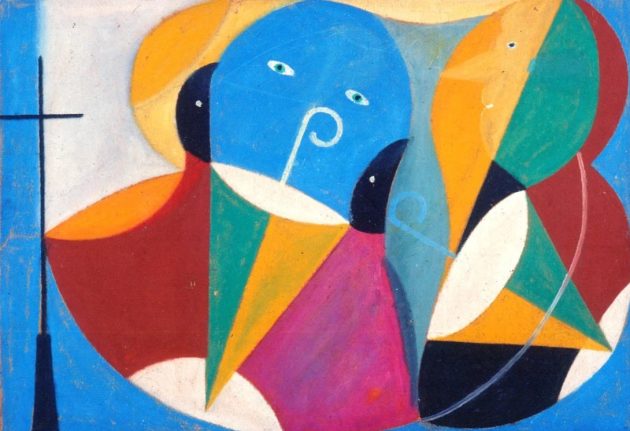

One of the patients/artists, now exhibited at The Museum of Images of the Unconscious, is Carlos Pertuis, a shoemaker with no formal art education, who was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1910. One morning in September 1939, rays of sunlight fell on a small mirror in his room: the extraordinary brightness dazzled him, and a cosmic vision appeared before his eyes: “God’s Planetarium”, as he put it. He shouted, called his family, and wanted everyone to see the wonder he was seeing. He was admitted to the psychiatric hospital that same day. The vision of “God’s Planetarium” was forever engraved in his memory. Encouraged by Nise da Silveira and her colleagues, Carlos worked intensely and produced about 21,500 works – drawings, paintings, sculptures, woodcuts and writings – until his death in March 1977. His works, along with art by Nise’s other patients, ended up exhibited in a groundbreaking show at the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo in 1949 (while in the postwar years in Europe psychiatric collections were not featured in art museums until the 1960s). Leading art critics were impressed by the quality of the works and pronounced it a renaissance of Brazilian art.

Curated selections of the best works from the patients’ art became the core collection of the Museum of Images of the Unconscious in Rio which Nise opened in 1952. The museum is still part of the hospital and holds the largest and most diversified collection of Outsider Art (Arte Bruta, or that by untrained artists) in the world. Over the years, the collection kept growing and added a second building called Espaço Travessia, which now occupies two floors in a former psychiatric ward at the Nise da Silveira Municipal Institute. Travessia’s purpose is to be a meeting place for artists, especially from the suburbs of Rio de Janeiro, to socialize, produce and promote their work. The professionals who work at the Institute also promote mental health through exhibitions, studios, dance and theatre rehearsals.

I met with the current member of the Travessia artistic community, Edson Luis Antunes (60), a former schizophrenic inmate who was treated with Nise’s therapeutic art approach. Edson was suffering from mental disorders and had multiple suicide attempts before he was hospitalized. In the course of the treatment since 2014 and after recovery, Edson has been transforming experiences and recollections of trauma, such as being confined to a straitjacket, to poignant surrealist paintings. Now he has a studio in Travessia, where he creates masterpieces of abstract and naïf art. The themes of his work move between personal memories and dreams of harmonious life in the greenfields, to mandalas and images of characters from African mythology taken from his religious experience. According to Edson, he found a “safe haven” at the museum. Edson now gives arts workshops around the city and will be featured in the upcoming virtual reality film Crossing through the world of images by Brazilian filmmaker Alexandre Muniz.

Unlike the Brazilian National Center for Psychiatry in Rio, most Brazilian mental institutions did not follow the experimental and poetic psychiatry of Nice Da Silveira. Instead of treating acute psychiatric in-patients, the large psychiatric hospitals in Brazil were operating in “feed and shelter” mode. Patients remember those asylums as prison-like spaces deprived of social contact, where they were occasionally allowed to go out for a game at a depressing football field and then locked in again. Federal reform of mental healthcare was only decreed in 2001 after various reports of mistreatments. Perhaps the most infamous was the death of psychiatric patient Damião Ximenes on October 4, 1999, investigated by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Damião was attacked, tied up and died as a result of the torture in the psychiatric hospital Casa de Repouso Guararapes, in Sobral, Ceara.

Sobral is known internationally as a place where Einstein’s theory of general relativity was proven in 1919. In Brazil, the city is also known for its excellent public education system, attaining near-universal literacy and dominating national assessments in reading and arithmetic – outscoring even affluent students in Saõ Paulo. I visited CAPS AD, Sobral’s Psychosocial Care Center, a lesser known gem and a testimony to the core changes to psychiatric treatment in Brazil. These care centres (known as CAPS in Portuguese, of which there are 2,947 in Brazil, 157 in Ceara and three located in Sobral) replaced traditional psychiatric hospitals after the reform of mental healthcare; they are very different from asylums. There’s a feeling of community created by the multidisciplinary team that provides care and rehabilitation to people with mental disorders, drug and alcohol addictions.

According to Bruna Kérsia Vasconcelos Santos, coordinator of the Sobral Mental Health Network, CAPS in Sobral is a national reference in creative development of mental health institutions, with the Go Crazy (Loucure-se) project, led by the patients (respectfully called ‘clients’ at the centers). The project includes journalism, podcasting, culinary classes, carpentry, employment workshops, paintings, cinema, theatre and sports groups and, for the last seven years, the musical band Tons and Ritmos.

Aurélio da Silva, CAPS AD nursing technician, is one of the founders of the band, who plays guitar, sings and teaches these skills to other band members, who are mostly patients. The band has played in various venues throughout the region, including special carnival shows. Aurélio says that Tons and Ritmos is open to anyone with the desire to play and is “a mix of DIY, art, dance and other expressions of the soul”. The band is popular not only with the patients, but with CAPS AD professionals who need these joyful musical moments, as they treat mental suffering on a daily basis. The band rehearsal is a space to talk about music, not illness.

In the words of Aurélio, Tons and Ritmos initially started as a music project, but evolved into forming a big family and personal hobby for all its participants. Douglas Prado, manager of CAPS, filmmaker and one the band’s instructors, reports that purchase of musical equipment is not yet funded by the government, leaving it up to the CAPS professionals, like him, to buy the instruments for the band.

Francisco Deassis Muniz is a 33 year-old cordel poet who was diagnosed with a mental disorder years ago after daily hallucinations and feelings of extreme loneliness and despair. It was then that the professionals at CAPS AD recommended music therapy. Deassis believed that in order to make music, a person had to be born with a gift and was a bit nervous to join the band. At the Tons and Ritmos rehearsals, he was welcomed and over time he started to loosen up and play some instruments. Before he knew it he was already performing, had made new friends and received a breath of fresh air amidst the chaos that used to inhabit his mind. Deassis is now the percussionist and composer of a popular song “Lunático“. One of the lines in the song (“You made the Universe party with constellations always shining”) echoes Nise da Silveira’s patient Carlos Pertuis visions of God’s Planetarium painted 80 years earlier.

Through attending the band workshops, Deassis learned to calm voices in his head, find inner peace, and express his emotions in a healthy way. Little by little, he noticed significant improvements in his emotional and mental state. His anxiety decreased, hallucinations became less frequent, and the feeling of disconnection from reality gradually dissipated. There are still challenges to face, but now Deassis and his bandmates know that they have a powerful tool by their side: music. Art used as therapy was the best medicine they have ever taken in their entire life.

Find more of Alex Minkin’s work here.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.