Mapuche Hunger Strike in Chile Highlights the Real Problem Facing President Sebastián Piñera

15 October, 2010This month marked 200 years since Chile achieved its Independence from Spain. Long before independence, however, even centuries before the first Spanish conquistadors led by Pedro de Valdivia made their claim to what is now Chile, this country was home to a group of thriving indigenous people known as the Mapuche.

When the Spanish arrived, they were met with great resistance from the Mapuche. The war, known as the War of Arauco, lasted more than 300 years, by some counts the longest war in history, and the so-called “pacification” of the Mapuche in southern Chile was not completed until the late 1880s.

Traditional Mapuche Ruka (photo by David Mauro)

The war left the Mapuche population significantly dwindled. Today only 5 percent of Chile’s population identify as Mapuche. In southern Chile, particularly in the Araucania region, the percentage is much higher. In the area of the country where the Mapuche once ruled, reminders of Mapuche culture are everywhere. Even in the region’s urban centers, streets are named after past Mapuche leaders Colo Colo and Lauturo. Still, even in these areas, the word “Mapuche” is regarded by many Chileans as an insult. It goes unsaid that nearly everyone whose ancestors lived in southern Chile is at least part Mapuche.

In Angol, the provincial capital of Malleco in the Araucania region, there is a seemingly permanent group of protesters outside the city’s jail. They are protesting the country’s anti-terrorist law, first enacted under the military government of Augustus Pinochet in 1984. The law dictates Mapuche can be charged as terrorism suspects, detained indefinitely and tried in military tribunal courts where they can receive far harsher sentences than in a civilian court. Similar scenes can be found in the cities of Temuco, Los Angeles, Valdivia, Puerto Montt and Osorno. Inside the jail, Mapuche prisoners are being held under the country’s anti-terrorist law.

The very name of the law sparks division. Critics say by labeling the Mapuche prisoners “terrorists,” the government only exacerbates the existing problems and makes it even more difficult for the Mapuche to find a place within Chilean society. Supporters of the law contend the actions of the prisoners are indeed terrorism.

“The Resistance is not Terrorism” (photo by Antitezo)

For over two months, more than 30 Mapuche prisoners have conducted a hunger strike to seek changes to the anti-terrorist law. On October 3, after the intervention of the country’s Catholic Archbishop, the strike looked to be reaching a conclusion. Several prisoners began eating, but the great majority have continued the strike. It had garnered substantial international attention, but within Chile the subject of the striking Mapuche remains one that most people would like to ignore.

The timing of the strike, which began just days before 33 miners were trapped in northern Chile, has come under criticism from some, including President Sebastián Piñera, whose popularity surged following the revelation that all 33 trapped miners were alive. As the strike continues, however, and the health of the prisoners deteriorates, it is an issue Chileans will not be able to ignore for long, no matter how much they may want to.

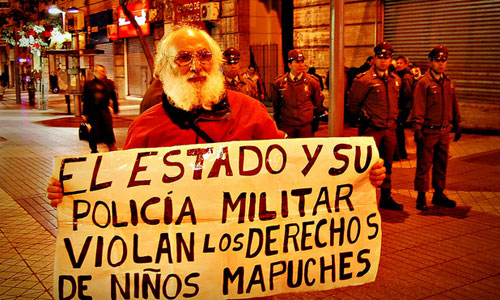

“The State and the Military violate the rights of Mapuche children” (photo by todonuestrosmuertos)

The prisoners have been joined in their hunger strike by four members of the Human Rights Commission in Congress. The same day the congressman, all members of the opposition, joined the strike Piñera introduced emergency measures to change the anti-terrorist legislation. This is not the first time such a bill has been introduced, however, and it remains possible, even with Piñera’s backing, it could fail due to opposition among some conservative legislators.

Although the Piñera government has vowed to support changes to the law, Mapuche protestors throughout the south are still being met with a violent response from the Carabineros, the country’s national police force. After years of tension, the relationship between the Mapuche and the government has reached a boiling point. If a prisoner dies during the hunger strike, violent protests are expected to break out throughout the region. Earlier this year, there were accusations that some Mapuche groups had ties to the FARC of Colombia and the ETA of Spain’s Basque country. Little evidence has been presented, but some Chileans now assume the most active Mapuche groups have at least some association, particularly with the FARC.

Mapuche March (photo by fotograma!)

Pinera’s government did not create the rift with the Mapuche, but like every government since Chile returned to democracy, they have struggled with determining how to handle it. Piñera, who was elected in January of this year and took office in March just days after an earthquake devastated parts of the country, made campaign promises that he would change the way government treated the Mapuche. He pledged to be a “voice for the voiceless.” Less than eight months into his presidency it may be too early to make any judgment of whether his government will follow through on his promises, but there is no doubt the hunger strike has brought the situation to a crisis level that is unprecedented. Piñera may regard the hunger strike as a distraction from his own stated priorities, but it could turn into a long term headache for his government if something is not done soon.

The government’s willingness to make some sort of compromise could be viewed as a win for the Mapuche, but they, perhaps more than anyone, realize it is too early to declare victory. Any change is likely to be relatively small and certainly not to the extent the Mapuche would desire. Chile may have celebrated its independence bicentennial last month, but the Mapuche are still seeking liberty and territory in southern Chile.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.