Between Rifles and Accordions – Collecting and Analyzing Music from the FARC

11 May, 2020Whilst homemade music videos produced by the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) have been circulating around forums and YouTube for some years, there has been very little effort to systematically collect and analyze the wealth of music produced by the group.

Rafael Quishpe is a political scientist and researcher at Rosario University in Bogotá, Colombia. I caught up with him about a project he recently conducted to fill this gap, collating and analyzing music produced by the FARC between 1988-2018. His project, Entre fusiles y acordeones: base de datos de la música de las FARC-EP (1988-2018), identified some 700 songs, but with many CDs in limited pressings and some works still not digitalized, he believes the true number to be well over a thousand.

His findings suggest music played a complex role in the organization, from fortifying ideological cohesion to motivating combatants. Through the ‘Culture Hour’, a compulsory hour of music, reading and dance, it also created important shared social experiences. With the state absent from providing even basic services in large parts of the country, FARC musicians were able to flourish as one of the principal cultural offerings.

Their music, therefore, displays a spectrum of styles, as FARC productions would mirror in rhythms and instrumentation popular regional styles as to ingratiate themselves within communities: vallenato in the north, llanera in Los Llanos. Lyrically, they describe episodes of the conflict, the organization’s core beliefs and their thoughts on the 2016 peace process.

Strikingly, Rafael grouped together students, professors and ex-FARC members to transcribe the songs and use their content as discussion starters for their respective experiences of the conflict. The lyrics, and accompanying artwork, can be found on their website.

Can you introduce your work and this project?

Sure. Since getting my MA in peace-building, I’ve been working on two topics: the political transition of the FARC, and the music generated by the group. This project, about compiling and analysing music produced by the FARC over a thirty year period, started from my Masters thesis, which I was studying for during the peace agreements. I was studying at the Public University, where there is a lot of support and even militancy for some armed groups involved in the conflict. FARC is a political, as well as a guerrilla, organisation. So there were a lot of people who were part of FARC but without being fighters, combatants, and I had classmates at the public University who were FARC members. It just didn’t come out until the peace process that they were part of the political arm.

In my thesis I was trying to look deeper into the role of music in the organisation. We’ve known for a long time that they were producing music, albeit with a very limited distribution, but you can follow some of the videos they post on YouTube. So my thesis was about trying to understand: what was the role of this music in daily life?

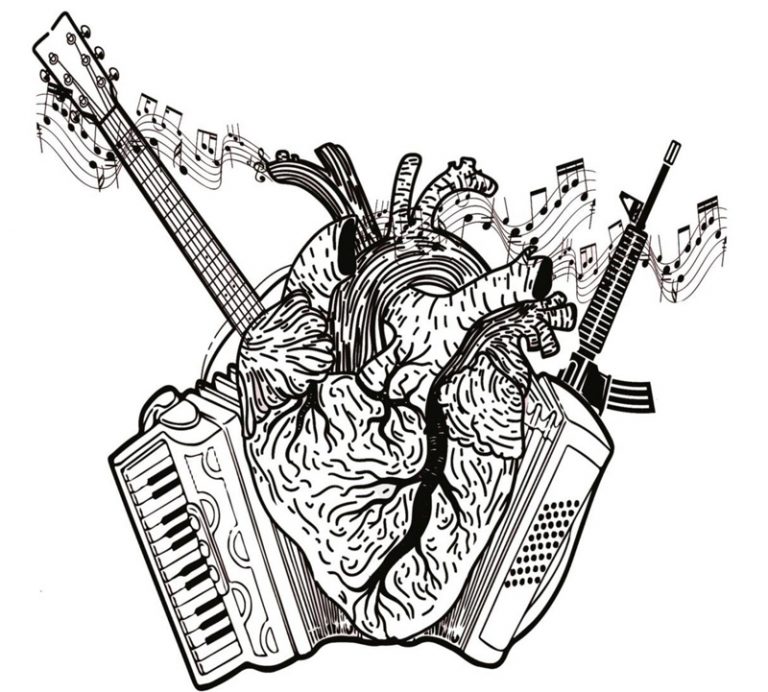

The project is called Between Rifles and Accordions [Entre fusiles y acordeones: base de datos de la música de las FARC-EP (1988-2018)] from a photo taken by an ex-FARC member, a rapper, called Martín Batalla. It’s a photo he took in a reintegration centre in the North, I think in the Caribbean coast, of a rifle and an accordion. And I think we mostly focus on the rifle, not on the accordions. We often focus on the violence, but not the other parts of their everyday life.

What did you find?

In analysing the music, we realised it served four important functions – three internally, and one externally.

Internally, music was used to fortify ideological cohesion between people, through the lyrics – intoning the values of FARC, their political beliefs. Secondly, it was important in permitting shared social experiences. For example, fighters in the jungle would unite around music and compose songs together. In FARC camps they have something called ‘The Culture Hour’, usually between 5-6pm, where they get together and discuss issues about the conflict, present their songs or dance – music is always a very big part. It’s compulsory, every day. So music is also a way of creating social cohesion between FARC members. The third role is for installing motivation. FARC has a lot of musicians and musical initiatives, but there are some who’ve received more support than others – the organisation has paid their production costs, to make CDs and albums. And these musicians also did ‘motivational’ campaigns in the camps, to motivate the combatants and raise their spirits.

Externally, the music served a role to connect the FARC with the regions and rural societies they inhabited. It’s not a coincidence that they use the rhythms or instrumentation from the region they settled in. In the Carribean coast the preferred musical style is vallenato, so FARC based there developed a whole body of work in the vallenato style. But if you go to the south of the country, in Putumayo or the border with Ecuador, the FARC adopted ‘popular’ Colombian music which is the most appreciated style in those areas. And if you go to Los Llanos, FARC play llanera style.

So the organisation had to adapt their music to regional styles in order to be able to carry out their political work. And this is very interesting, because if you compare it with studies of the role of music by American forces in places like Iraq, Afghanistan or Sierra Leone, they show that music was used to divide societies, as a psychological tool, even a weapon. But here we’re showing that music here has a different role, including connecting the organisation with civil society.

You have to realise that the Colombian state is not present in huge swathes of the country: not with basic services, healthcare or education. And much less with culture – there’s no cultural offerings by the state in these places. So the FARC also became cultural promoters in remote regions of the country. FARC orchestras might be the only source of public entertainment, those who play at birthday parties or gatherings.

How did you go about the project?

So the first stage of the project was working out what role music played for the FARC. The second was then to go deeper into the lyrics. We began a project at the Colombian Insituto CAPAZ, a joint project between German and Colombian Universities. And we included in our team professors and students from partner universities, but also ex-combatants from FARC. We compiled all music produced by the FARC in these thirty years, then we transcribed the lyrics as a way to debate their content. Not only were the results interesting, but the project and process itself was fascinating. It was a project in comprehension, empathy and ultimately reconciliation. Because a lot of the students, for example, either didn’t have a lot of knowledge about FARC or, more commonly, had a lot of preconceptions and prejudices formed by the media. So the project was most successful in deconstructing these stereotypes each group had about the other, and even create friendships between both groups. We compiled over 700 songs from the FARC during 30 years, which we know isn’t the whole story, but the others are very hard to find. I’m sure there’s over a thousand recordings, and many more that were never recorded.

One thing I think was very interesting about our project was putting ex-combatants in the role of researchers; there are a lot of advantages, and questions, raised by appointing them as researchers of an issue they are party to. Today, four years after the peace process, a lot of foreign researchers want to come to Colombia, but people living in affected communities are tired of interviews and of being extracted for information that they rarely understand where it is destined for. This makes new research difficult. But this project made communities participants, fundamental parts and decision makers in this project. So for example, we have some money dedicated to the dissemination of our findings, and we put the question to them: how do you want to spend the money? And they decided to make three lyric books about specific themes of the conflict: one that collates songs about the geography of the country, another on peace and reconciliation, and another on the daily life of the FARC. And all the diagrams and illustrations are made by ex-FARC members.

What were your main takeaways personally?

In peace and conflict studies, there’s sometimes the expectation that the music itself has the capacity to reconcile opposing groups. But a lot of FARC songs – whilst there is a lot of music that talks about reconciliation and peace – there’s also a lot of songs commemorating military operations against the enemy. I realised the music can be used to reconcile, but these kinds of songs don’t hold that power – but all the more reason why it’s important to discuss that.

As a researcher, there are certain places which are harder to reach. But working with ex-combatants who had access to much more of the material, connections made the whole process much more thorough. If I’d stuck to researching on YouTube, you can find a hundred or maybe 200 songs. But the other 500 we found through the network that opened up to us by including ex-combatants. I think that’s a lesson for any future projects that want to study any aspect of the FARC – to know that many of them demand to be involved, to participate, directly in projects. This process might even be as important as the results of any study.

You can find the outcomes of the project, including the three lyric books, as well as audio-visual material (including songs) at instituto-capaz.org/en/la-paz-camina-farc-ep-songbook

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.