Defiant Museum: The Life of Art Critic Marta Traba

25 February, 2013La Violencia, a 1962 painting by the Colombian artist Alejandro Obregón, is a painful work to view. The image is of a naked, pregnant woman lying horizontally in the dark, pushed up close to the viewer; her face is bleeding, and her posture looks like that of a broken doll. Something terrible — the viewer doesn’t know exactly what – has clearly happened.

The title of the painting is a play on ‘La Violencia’, the country’s decade-long civil war; the work was painted just after the dictatorship of Gustavo Rojas Pinilla, the president who claimed to bring peace but ultimately resorted to death squads and the silencing of suspected opponents. The reason why the painting is so strong, though (and the reason why it’s been so influential) is precisely that it’s not ‘committed’ political art with an obvious message.

Writing on the work when it was sent to the Museo de Arte Moderno in Bogotá, art critic Marta Traba (1952-1983) praised this very quality: “Going beyond a strictly painterly solution, one notices Obregón’s symbolic will, his desire to get at the contents indirectly.” His work doesn’t resort to shrill accusations; it is instead “as solitary as the fallen woman” and, in its blackness and emptiness, “as apt as she is at filling the world with forms”.

This is the kind of work Traba spent her life searching for; it is the kind of work she thought could offer Latin America a way to navigate its traumatic past, and at the same time carve out a new identity for itself. In addition to being a critic of art, Traba was herself a novelist; and so she knew first-hand the difficulties of taking on important themes without giving in to cliché, propaganda or sentimentality.

***

Marta — she liked to be called by her first name — grew up in Buenos Aires and went to university there, but she received her postgraduate education in France. It was in Paris, too, that she met her husband, the Uruguayan literary critic Ángel Rama. Later she moved to Colombia when Rama was offered a job at the newspaper El Tiempo; Marta taught at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Her arrival in Bogotá had been somewhat unexpected, but she set herself to work writing on the abundance of artists there, and rejuvenating the contemporary art scene. (She was the one who founded the museum where Obregón’s work was displayed.)

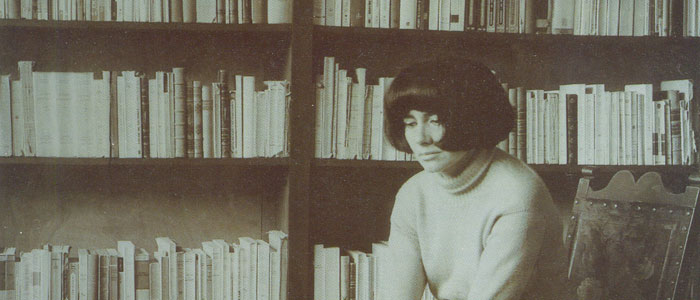

There are two famous shots of Marta. In one [the image at the top of this article], she is sitting on a hard backed chair in front of a crammed bookcase, wearing an elegant turtle-neck and trousers, leaning forward, pensively: somewhat sad, somewhat fierce. Her thick black bob with fringe looks immaculate. The other is a mug shot; her head rests on her hand, her eyes stare somewhere upward and to the left. Once again, her hair is bobbed and immaculate; once again she looks somewhat pensive.

These pictures capture one aspect of Marta, perhaps even that aspect she hoped to represent to the world. But most personal accounts give a somewhat different picture. Marta is always spoken of as a terribly happy person, as well as ‘smart’ in the sense of possessing a certain elegance in mannerism alongside her razor-sharp erudition.

Accounts also often mention that she hardly ever pulled punches with what she thought. If you were an artist she liked, you could count on incredible generosity from reserves undreamed of; if your politics weren’t to her taste, she would go on the attack. In an interview with the Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska, she recited a list of things she liked and didn’t like. The ‘for’ list included Allende’s Chilean government, a free Puerto Rico, and the Cuban Revolution until 1971, when Castro aligned himself with Russia. The ‘contra’ list included the 1961 U.S. invasion of Santo Domingo, the invasion of Russia into Czechoslovakia and Afghanistan, and Soviet communism, which she thought a negation of socialism.

Mexican artist José Luis Cuevas — himself famous for courting controversy for calling himself a ‘gato macho’ and seducer of women while still with his wife, and for having taken a photograph of himself every day since 1955, among other things — was a good friend of Marta’s. In an account he remembers her strong opinions, which were what gave her art criticism its clarity and force. When he first met her, he says he was astonished. “I have various critical pieces you’ve done on me,” he’d told her, “and what astonishes me is that while reading, I imagined the writer to be much, much older.” She laughed, amused at the thought of him imagining her a viejita. Her mind was that of a wizened, arch old lady in the body of a pretty young woman.

Saying exactly what you think can, in certain circumstances, give you a reputation as provocative; in others, it can get you in serious trouble. During the occupation, while Marta was teaching at the Universidad Nacional de Bogotá, a military man phoned up to ask where certain statues acquired by the university should be put. Marta answered that it was absurd to worry about something like that when the university was being devastated, when students weren’t going to classes and the army was destroying classrooms. She invited him to stop by and have a look. In response she was given 24 hours to leave the country with her family, a forcible deportation to Argentina.

Marta reacted calmly. She succeeded in bargaining the time up to 48 hours; meanwhile, her friends were able to launch a campaign that went to the heights of the government, advocating that she be permitted to remain. It worked: the presidential dispatch was sent. She could stay.

Even if she wasn’t officially exiled then, however, Marta did continue by choice to float from place to place. For a few years, she and her husband went to the United States. She didn’t like it overly much, mostly because of its political policies (the country’s various interventions featured heavily on her ‘against’ list), but also because she found it, quite frankly, somewhat boring. She enjoyed the sense of security she felt there, though, and liked being able to send her children to school without worrying.

Even then, her feelings towards Argentina were ambivalent. When the United States refused to renew her visa, she went back to Colombia; the sharp edges of her accent began to wear off, becoming slower and rounder, more typically Colombian. The populist policies of Perón scared her a bit; she’d never liked the agitating mobs or the anti-individualist collectivism she thought he embodied. But when, in a 1976 coup, the Argentine military seized power, this fright burgeoned into pure terror. The ‘national reorganisation process’ — now called the ‘Dirty War’ — had begun, during which over 13,000 people simply disappeared. Marta’s exile had become official.

Conversación Al Sur, written in 1981 and Marta’s most famous novel, is about Argentina’s Dirty War. To say that, however, may immediately put off the reader tired of the demands for justice, the street protests, the placards reading ‘NUNCA MAS’ that the period now evokes.

Luckily, the book is far more subtle than that. Two women — one older, one younger — sit together in a dilapidated room in the Barrio Sur of Buenos Aires. Each has been involved in resistance movements, each tortured by the military. The political angle of the book comes out in occasional references: to the grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, who go marching day after day asking for their daughters, sons, and grandchildren; to the picardía, the cattle prod used as an instrument of torture. But some of the worst pain inflicted seems to have been psychological. How is it that two women with so much in common simply can’t talk directly to one another?

Over the course of her career, the question of how to represent recent history in art and words increasingly became Marta’s concern. How to discuss the undiscussable? It wasn’t just politics or the human that had been debased. Marta saw her work as a constant struggle against the degradation of language — against bureaucratic government-speak, as well as the well-intentioned but shrill rhetoric of protestors for human rights. On the other hand, to remain silent would be to prolong the trauma. To state what happened in a ‘realist’ way may be necessary for justice, but it wasn’t complex enough for literature; to try to forget would be giving in.

In the novel, this uncertainty permeates everything: “I would like to tell you more intimate things, but so many years of civic education have castrated me, such that it’s not clear if what I’m saying is about liberty, or about more personal feelings.” There is a constant sense of guilt over reciting a “rosary of insignificances”: “Whom to tell these things? They’re unimportant and interest nobody, and have only stayed imprinted in my memory from an injured self love.”

Marta’s non-fiction work, in her essay collection El Museo Vacío among others, explored the question of how Latin American art should take up the European modernist heritage. European man, having experienced the crisis of war, had begun to feel a constant sense of threat, to lose his sense of humour, and to distrust any idea of a universal model like Le Corbusier’s Modulor. These same issues applied for the Latin American avant-gardes, but were complicated by an uncertainty about how to use these continental conceptual tools when talking about different regional realities.

Inspired by ideas from both Europe and in Latin America — Alejo Carpentier’s Lo Real Maravilloso, Levi-Strauss’ belief in myth as “a model created to overcome contradiction”, and Mircea Eliade’s conception of myth as reality — Marta theorised the idea of a ‘cultura de resistencia’. Trash, strips of metal, fragments of dreams, cut-off dialogues, unlovely bodies: most things could be art, so long as they emerged organically from the surroundings without resorting to stripped-away accusation (too similar to the tone of an authoritarian order) or terrified silence (too similar to the silence of a night-time arrest). Everyday things can be made uncanny, so that they speak for themselves.

In Conversación Al Sur, monologues and memories are told in a way that makes them sound simultaneously unpolished, somewhat fantastical, and utterly truthful. It can sometimes be tiresome to read novels set in periods of dictatorship; but Marta’s approach of searching for a reality deeper than ‘realism’ ultimately makes everything more fresh, more believable.

***

In a series of television programs made for Bogotá’s public television station on the history of modern art, Marta lectures in a conversational tone, while moving constantly about the city. In one scene she wears an anorak and carries an umbrella, with a busy urban street as her backdrop; in another she comes toward the camera, having apparently just emerged from a walk in the forest. She talks in a monotone, rapid-fire way, as if to convey the maximum information possible in the short time she has.

Marta’s death was a tragic one. She died on a flight taking off from Madrid to Bogotá, where she had been invited by President Betancur to attend a ‘First Meeting of Hispanic-American Culture’. Her husband, along with several other prominent artists and writers, perished along with her. One imagines she would be impatient with any overlong show of grief, however. When Marta left this world, glimmers of hope were once again emerging: 1983, the year of her death, was also the year the Argentine military junta was toppled, a new president was elected at the polls, and the country returned to constitutional rule. Artists in Argentina, Colombia and other Latin American countries continued to make thoughtful art playing with Marta’s themes of myth and memory, and increased their collaborative efforts in the attempt to make sense of those decades in which a political dystopia had been terrifyingly mirrored across countries.

Meanwhile, just as in her television program, Marta sat perched up on a wall in some unknown place, legs in white stockings crossed, hair bobbed and immaculate, watching it all unfold.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.