How Jazz Provided a Gateway to Cumbia Becoming The Most Popular Rhythm in Colombia (and across Latin America)

05 October, 2021Cumbia is the backbone of Latin American music; it has a danceable and tropical rhythm that can be heard from Mexico to Argentina. Gustavo Cordera, singer for Argentine rock band La Bersuit Vergarabat, once said “Latin rock is jealous of cumbia music”, in reference to cumbia’s all-encompassing popularity. Carlos Vives, the Colombian singer-songwriter, described cumbia’s role in Latin American culture in his song “El Rock De Mi Pueblo” with this analogy: “on the Magdalena river, the cumbia was born. As the blues from the Mississippi [is] the cradle of rock’n roll.”

It was on the Magdalena river that cumbia was born, and for the majority of its history the style was constrained to that area and the surrounding region. However, this changed in the 1930s and 40s when musicians such as Lucho Bermúdez began to play cumbia, and other traditional musical styles, with a big band jazz orchestra. The result was that cumbia became the most popular genre in Colombia and Latin America.

Origins

The truth is there is no certainty regarding the origins of cumbia. Most historians believe this musical style came from the indigenous groups in the Magdalena river and the Caribbean region. In 1580 the governor of the Providence of Santa Marta wrote that “the Indians drink and do parties with a reed flute, and produce music that seems to be brought from hell.” The reed flute the governor describes is the gaita, a popular instrument that is still used today. For example, the much-loved Gaiteros de San Jacinto use the gaita as the principle instrument for their songs and performances.

Other historians believe that cumbia arrived from Africa with the transatlantic slave trade. They point out that the word cumbia may come from the word kumbé/cumbe from the Bantu languages. They also point out that the cultural importance of dancing in Western African cultures is replicated in Colombia through cumbia music. For example, in this live version of the song “PrendeLa Vela” by Totó La Momposina, dancing is as important as the musical performance.

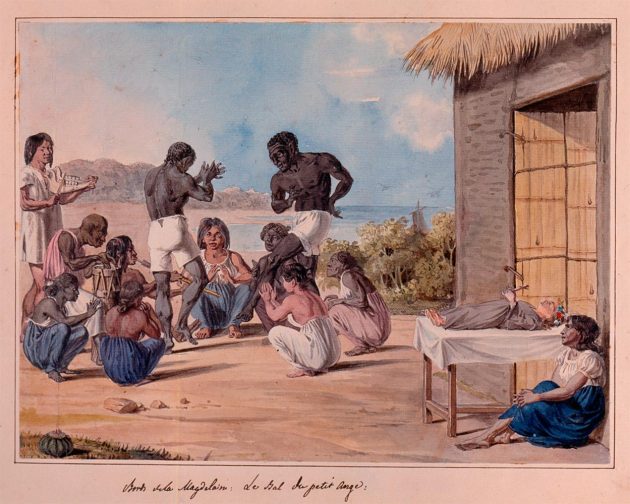

Whatever its initial spark, most researchers see cumbia’s evolution as a product of encounters between Africans and Indigenous communities in the Colombian Caribbean. In the image below you can see a celebration on the Magdalena river in 1823 with Afro-Colombians dancing and indigenous musicians with instruments, including one with a gaita.

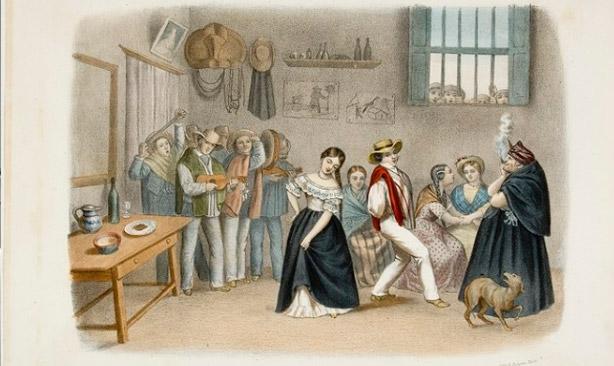

Before cumbia became the most popular music in Colombia, there was bambuco. A traditional music and dance style from the Andean region, similar to the European waltz due to its ¾ or 6/8 metric. This similarity made it very appealing to the 19th century elites.

When Colombia won its independence from Spain, the political and economic elites needed to construct a new national identity for the newly independent country. A myth was created by the elites that elevated bambuco as the original Colombian music. For example, Rafael Pombo, arguably the most important Colombian poet from the 19th century, wrote:

“To ward of boredom,

Of this dreadful living

God give me one bambuco,

And to the point, holy remedy.”

The song “El Regreso” from the composer Efrain Orozco Morales provides a great example of a traditional bambuco, while the performance of “Fiesta en Sutatenza” by legendary pianist Ruth Marulanda is a great example of the nationalistic music movement that aimed to create an identity based on the traditional rhythm.

The hostility of the elites towards music that was not bambuco, plus racist and classist attitudes, and the goal of homogenizing Colombian culture based on the Andes region, led to many musical genres in Colombia remaining mostly unknown outside of their traditional geographic boundaries. Conversely, the same elites showed great interest and desire for foreign music and culture, especially from the United States.

Jazz and Radio

“Nowadays … girls are fascinated by the impertinent mumble of American jazz. The banjo and drums are as indispensable now as the violin and cello used to be. … That music is noise, or rather, a torrent of noises. … Teenage girls … sink into the foxtrot.” These words come from an imaginary interview that Mexican journalist, José Luis Velasco, conducted with a pianola in 1921. They provide a wonderful example on how quickly jazz took hold on Latin American elites.

Why were Colombia and Latin America as a whole so eager to embrace jazz music that is so clearly defined by the black experiences in the United States, while being dismissive of their own folkloric music?

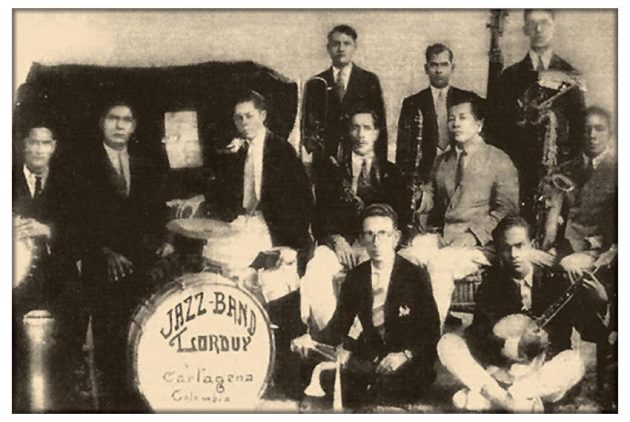

The answer might be that the first jazz recordings were made by an all-white band, due to the prejudices and racism in the United States that limited access to recording studios and publicity for African Americans. The all-white Original Dixieland Jass Band represented a facet of United States culture that Colombian elites wished to imitate, even while ignoring the social context that led to the birth of this musical genre. It became acceptable for Latin American elites to consume and produce jazz music. In 1920, just three years after the first jazz record, the first jazz band was formed in Colombia: The Jazz Band Lorduy from the city of Cartagena.

Jazz was so new in the country that its members had to import their instruments from the United States. The Jazz Band Lorduy quickly became one of the most famous bands in Cartagena and the Caribbean, playing in parties, public events, and radio stations. Although there are not any recordings from this band, one of its members was the renowned composer Adolfo Mejía, who was the first to incorporate cumbia into a classical composition in the third movement of his “Pequeña Suite”.

The first album made in Colombia was recorded in 1943, so musicians in the 1920s and 1930s depended on the radio to get exposure and economic success. People around the country tuned in weekly to listen to different bands and orchestras performing jazz. As their popularity grew, the hunger for new music in the audience also grew. For example, Cuba’s Sexteto Habanero, the first to ever record Son Cubano, was very popular in Caribbean cities such as Barranquilla.

Their success inspired many local musicians to start exploring folkloric rhythms; which at the same time made Colombian audiences more prepared to listen to styles that had previously been dismissed. Ultimately, the popularity of jazz quickly diminished the elites’ preferences for bambuco.

A great example is the Orquesta Emirosa Atlántico Jazz Band, the in-house big band jazz orchestra for a radio station in Barranquilla that was very popular in the 1930s. Their song “La Arenosa”, which was recorded during a live broadcast, sent to Argentina to be pressed into a record, and imported back to Colombia for retail, is one of the earliest recordings where a big band jazz ensemble is playing folkloric rhythms.

Lucho Bermúdez and Cumbia: Travelling to Record

Lucho Bermúdez (1912 – 1994) was a composer, arranger and bandleader who dedicated himself to arranging the musical styles of the Colombian Caribbean for a big band format. He learned his musical craft from his uncle and the local military band, and composed and recorded more than a thousand songs in his lifetime.

His prolific career started in the 1930s, getting recognition as a performer, arranger and band leader in the radio stations of Cartagena. His first gig as band leader was for the Radio Fuentes Orchestra, later followed by the Caribbean Orchestra. Bermúdez’ compositions and arrangements of cumbia, and other musical genres of the Caribbean, made him one the most famous musicians in the country. His fame grew so much that in 1943 he was invited to perform in the exclusive Metropolitan Club in Bogotá with a big band orchestra, 23 years after the formation of the first jazz band in the country.

Despite his success as a bandleader and composer, Bermúdez realized that he needed to record albums to grow artistically and economically; and that to record a big band jazz orchestra he needed to travel outside of Colombia. In 1946 he left for 10 months to Argentina, invited by the famous record company RCA Victor with the purpose of making several albums. This was probably the most prolific and productive time of his career. The album Tolu is a great example of his work and style during this period.

Lucho Bermúdez was not the only Colombian artist to travel to make records and for better economic opportunities. For example, El Cuarteto Imperial, a more traditional cumbia ensemble, found great success in the 1960s when they relocated to Argentina. Their song “De Colombia a la Argentina”, describes their journeys through South America and the many places they performed: “I travelled to La Pampa, Tucumán and Mendoza. I saw malambo, zamba and chamamé dances. In Santiago and Buenos Aires they also dance cumbia; like in Colombia they dance a tango from Gardel.”

Lucho Bermúdez returned from Argentina as the most popular artist in Colombia. He finally had his own orchestra and was hired to play at the Hotel Granada in Bogotá, the most exclusive hotel in the country. In 1948 Bermúdez received a very lucrative offer for the position of radio director at the station La Voz de Antioquia, and the opportunity for his orchestra to be the house band of the new Hotel Nutibara, famous for its modern architecture. For more than 15 years his orchestra played weekly shows at the hotel, making it one of the most famous music venues in South America.

By 1952 Bermúdez’s fame had grown so much that he was invited to record in Mexico, the centre of tropical music. Since the late 1940s, the Central American nation had been experiencing a musical boom led by Agustín Lara, Toña la Negra, and María Luisa Landin.

However, Lucho Bermúdez was not the first Colombian to introduce cumbia to Mexico. In 1943 Luis Carlos Meyer, a great cumbia composer that has been forgotten, relocated from Bogotá to Mexico. Mayer provided many songs to Mexican singer Tony Camargo, who was obsessed with the music of the Caribbean despite never visiting the region. Together they recorded the song “Micaela”, probably one of the first cumbia songs ever recorded.

In 1953 Bermúdez appeared in the movie My Father Was at Fault with Mexican actress Meche Barbra. He performed with the orchestra of Bebo Valdez a version of the song “Prende Una Vela” with mambo arrangements, to make it more appealing to international audiences. The dancing, the style, and the tropical aesthetics of the movie would become the standard, and cliché, in the Caribbean for the following decades. My favourite collaboration from this period is the song “San Fernando” commissioned by a very exclusive social club from Cali, and performed with the legendary Cuban singer Benny Moré.

After a successful year in Mexico and Cuba, Bermúdez returned to Colombia in 1954. Mexico continued to be the centre for tropical music during the 1960s, where many Latin American composers and performers, such as Celia Cruz, found economic success. Probably my favourite song from this musical period is “La Pollera Colorá”, composed by clarinet player Juan Bautista Madera Castro and inspired by Mirna Pineda, a woman that lived in Barrancabermeja, a port city on the Magdalena river, and made famous by the iconic Mexican singer Carmen Rivero.

Electronic cumbia

The rise of rock n roll led to the popularity of jazz diminishing both in North and South America. During the late 60s and 70s a new subgenre of cumbia was born in Lima, Peruvian cumbia, or chicha. In chicha cumbia – chicha being also the name of traditional alcoholic drink from the Andes – the accordion and wind instruments were replaced by electric guitars and synthesisers; Colombian cumbia was mixed with new genres coming from the United States and England such as pop, rock, surf, and psychedelic music. A great example is the song “Sonido Amazonico” from Los Mirlos. Another example is the cover of Simon & Garfunkel “The Boxer” by guitar legend and cumbia musician Juan Carlos Denis, one of the pioneers of the cumbia santafesina genre developed in Argentina.

Often these new styles of cumbia were dismissed by Latin American elites as music for the working classes. However, in Colombia there are examples of incorporating these new styles. A great example is “Cariñito” a song composed by Peruvian Limeño Ángel Aníbal and later performed by Colombian singer Rodolfo Aicardi, where he mixes the electric guitars of chicha with a more traditional orchestra (Lila Downs also has a version of this song).

From the 1980s onwards cumbia’s popularity in Colombia started to decline as new tropical styles emerged and gained popularity, such as salsa, merengue, and bachata; and later champeta, and reggaeton.

Since the early 2000s there has been an interest from academics and music aficionados in exploring, recording, and preserving cultural expressions that are disappearing in the contemporary world. A great example is the rediscovery of the Gaiteros of San Jacinto, who play cumbia in the style that was common before Lucho Bermúdez and the big band jazz orchestras.

The rise of streaming services and digital music has also gone hand-in-hand with a resurgence worldwide in vinyl. In Colombia many vinyl records from the 40s, 50s, and 60s have become very valuable and desired. This resurgence has coincided with the work of English musicians such as Quantic and El Búho who combine electronic music with Caribbean styles such as cumbia, porro, currulao, mambo, and reggae. Both of them have been accused of cultural appropriation, of being “white boy(s) playing in laptops black music.”

I would argue that their approach of mixing cumbia with electronic music was the same that Lucho Bermúdez used by playing traditional rhythms with a big band jazz orchestra, a combination that made cumbia the most popular style in Latin America. For example the song “Cumbia Sobre el Mar” was composed by Colombian composer Rafael Mejía Romani, inspired by a beauty queen from Barranquilla in 1962. Then it was re-recorded in 2010 by Quantic in Colombia, and remixed in 2018 by El Búho. (El Cuarteto Imperial also recorded this song in Argentina!)

Why is cumbia so popular? Some have claimed that it is because it has a simpler rhythm than other tropical genres such as merengue and salsa. Maybe another reason is its ability to adapt, change, and integrate itself with different cultures, styles, and instruments, as it has done numerous times through its history.

Cumbia has changed through the centuries from indigenous parties with gaitas on the Magdalena River to mixing consoles around the world; sounds that were born in a small part of the Colombian Caribbean truly have universal appeal.

Santiago Flórez (@rflorezsantiago) is an anthropologist, educator, writer, and illustrator based in Bogotá, Colombia.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.