The Magic Realism of Gabriel Garcia Marquez

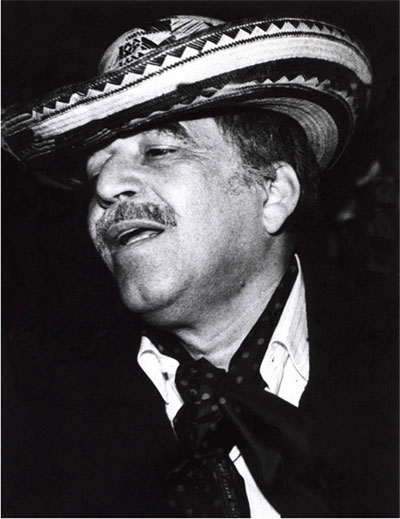

29 March, 2011Gabriel Garcia Marquez is one of the most famous Latin American authors of all time. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982 and is best known for the novels One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera. He has also become synonymous with magical realism a style that became popular as part of the Latin American boom in the middle of the last century. But what is magical realism and why did ‘Gobo’, as he’s affectionately known in the Americas, use it in his writing?

Marquez was born in the town of Aracataca in Colombia March 6, 1927, raised as much by his grandparents as his parents. He began studying law at the University of Cartagena but left to pursue a career in journalism.

He began writing fiction, and following initial success, published One Hundred Years of Solitude in 1967. It follows seven generations of the Buendía family in the fictional town of Macondo. The novel is considered a mainstay of magical realism with magical elements interwoven into seemingly ordinary situations.

He began writing fiction, and following initial success, published One Hundred Years of Solitude in 1967. It follows seven generations of the Buendía family in the fictional town of Macondo. The novel is considered a mainstay of magical realism with magical elements interwoven into seemingly ordinary situations.

There is the ascension into heaven of a character as she does the laundry, the Colonel who knows when people are approaching, and the figure of Melquiades who returns from the dead to live in the Buendia’s attic.

Magical realism grew with the boom in Latin American literature. Jorge Luis Borges, the ‘pre-boom’ Argentinian writer was perhaps the first successful author to use the genre effectively. The critic Angel Flores was the first to use the term about the work of Borges, appropriating it from the world of art where it had been used by German critic Franz Roh in reference to art in the ‘New Objectivity’ movement.

Magical Realism has been largely attributed to Latin American literature, with works from other parts of the world more quickly labelled as fantasy or science fiction. It is separate in style, not as escapist. It is as much about the realism as the magical. It isn’t speculative as with science fiction.

While in Macondo the inhabitants accept ascension as an occupational hazard when it comes to the laundry, they marvel at ice and don’t take to the cinema, convinced they are being tricked.

Success in Latin America, especially during the 60s has been attributed to the close relationship the modern and the traditional world still had to each other at the time in the region.

On being asked why Europeans didn’t ‘get’ magical realism Marquez himself said, “This is surely because their rationalism prevents them seeing that reality isn’t limited to the price of tomatoes and eggs.”

It’s a view that is shared with Philip Swanson, professor of Spanish at Sheffield University, “Essentially, the idea is that our perception of reality is determined by our cultural assumptions. The people of Macondo think nothing of a young girl ascending into heaven or a priest levitating after drinking a cup of hot chocolate, but they are amazed and bewildered by trains, record players, films and false teeth. So, our so-called First-world vision is not the only way of understanding the world.” Professor Lawson told me.

He continued: “It came to prominence in Latin America but did go on to be enormously influential in world literature. Perhaps it seemed to happen in Latin America first because of the coexistence of modern and indigenous belief systems or the coexistence of rapid urban development and ongoing rural underdevelopment. But writers like Salman Rushdie, Arundhati Roy, Ben Okri, Louis de Bernieres, Toni Morrison would not be what they are without the influence of Magical Realism.”

The subversion of what is normal and promotion of the alternative has also led some to suggest the genre is political subversive. Given the region’s history of power, from colonial to dictatorial, this could also be another explanation for its development in Latin America.

Marquez explores many themes in his stand out work, from people’s inability to escape time, fuelled by the repetition of names for multiple characters, to the circular notion of time; the book’s sense of solitude with no character finding true love could make the novel depressing, but the magic lifts this to produce wonder rather than sadness in the reader.

The book follows the popular narrative of the Colombian nation and has been widely translated, becoming the best selling work of the author. He began writing the book because he wanted to write about the town where his grandfather had lived.

The quote on the billboard outside the town of Aracataca celebrating its most famous son reads, “I feel Latin American from whatever country, but I have never renounced the nostalgia of my homeland: Aracataca, to which I returned one day and discovered that between reality and nostalgia was the raw material for my work.”

When people look at Marquez’s work and see the magic in it, that’s one side of the coin, perhaps the other lies in the more mundane and close to home.

Recommended Reading:

One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967)

Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1981)

Love in the Time of Cholera (1985)

The General in His Labyrinth (1989)

Of Love and Other Demons (1994)

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.