‘Epicentro’: An Idiosyncratic Eulogy for Havana

08 October, 2020A burnished man, 40’s, wall-eyed, unshaven, his hair slicked down by the salt spray. He clamps his teeth on a home-rolled “puro,” the tail of a tobacco leaf lifted by the breeze to flap across his grey and black mustache, as he stands, still, with the Caribbean desultorily scaling the sea wall behind him. Our man is silent before the inquisitive camera. In his bearing he suggests the grungy grandeur of La Habana.

The sea grows, and we’re pulled back and away as the swells crash over the Malecón, their grumble a fury now, punishing. A canon appears in the foreground. The scene is all about might.

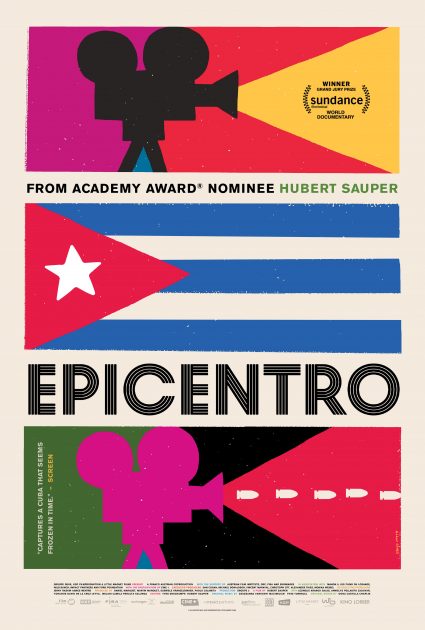

Epicentro (2020), the documentary film written, produced, directed and narrated by Hubert Sauper, lays before us an idiosyncratic eulogy for Havana, and by extension for Cuba. (Sauper is the director of Darwin’s Nightmare, 2004, and We Come as Friends, 2014.) Baptized by Columbus, “The most beautiful earth that human eyes had ever seen,” Sauper tags the Caribbean’s largest island a “Utopian island, a place where peace and justice prevail, a place where nobody owns anything, and everyone has enough.” We find in Epicentro a number of liked-minded Cubans.

Sauper’s Cuba is at the “epicenter of three dystopian chapters in history:” the slave trade, colonisation of the New World, and the consolidation of power into modern empire, i.e., under the United States. He shows how, with the advent of mass media, beginning with cinema, the U.S. premiered and honed a latter-day imperialism that colonises the minds and the culture of peoples world-wide.

Epicentro offers a potpourri of free-wheeling and well-programmed cameos that speak to the worldliness, the smarts and the resiliency of the Cuban people under the shadow of the US’ battle to destabilise and control this much-coveted territory. Sauper is to be commended for alluding to the US aggression and the fierce animosity between the two rivals without irritating or cudgeling his viewers with polemic or propaganda.

Dramatic and comic both is the director’s case against the US for fabricating the generally accepted account that the Spaniards blew up the U.S. Battleship Maine in the Bay of Havana, in 1898, impelling the US to retaliate and rid Cuba of its villainous overlords. Which they did, only to wrest control over the island for themselves until Fidel Castro liberated it from US.-supported dictator, Fulgencio Batista, in 1959. Sauper, along with animated cartoonist Juan Patrón, show how easy it would have been, even way back in 1898, to splice footage from different sources to simulate the Spanish fusillading innocent Cuban citizens, and, with model boats in a bath tub, cigarette smoke, and the explosive sound of a small firecracker, fake the blast that destroyed the Maine, all on camera. This cleverly crafted fiction underscores with frightening absurdity the ease with which cinema, this new “machine of dreams” on its way to be headquartered in Hollywood, USA., would maximise its leverage over the masses worldwide, blinded by the fantasy and the chintzy tinsel.

There’s nary a Kodak moment in Sauper’s rendering of La Habana. His intention is rather to root out cityscapes of once majestic, now bedraggled, buildings; just plain women folk on the street with curlers in their hair and sass on their feet; kids frolicking in the amusement parks of apartment house rooftops; street-front businesses of all stripes adorned with posters of Fidel or Che; and the shameful trappings of mega-wealth: forbidding hotels with rooms at eight hundred dollars a night, and a “centro comercial” replete with over-the-top shops that could easily be in Dubai.

Sauper unfurls much of his story in the company of three consorts, Annielys and Lioneli, a pair of vivacious tweens, and the astute and seductive Feña, about fifteen to twenty years their senior. With their spunk and brio they’re like a maypole (or should we say epicenter?) around which the city winds and unwinds.

The tweens act as tour guides, tooling around town with the crew, ready to offer their opinion on just about everything from the vantage point of their precocious world view, some of which comes from their exuberance and curiosity, some clearly rehearsed at school. Feña is the film’s most endearing character. Her smile is captivating, often ironic. To much enjoyment, especially her own, she flirts with the camera, too.

Sauper makes his own mischief on the streets, enfolding into the crew a voluble guy, big and burly with flaming red hair, gold earrings, and a big heart, who’s a master at one-liners. With conviction and gusto he tears into tourism, a problematic industry on the island that reflects “humanity at its worst.” In a brazen gesture, our red-bearded “observateur” essentially turns the camera back on the cineaste, asking him, “Just how much is cinema like tourism?”

Sauper bolsters the argument against tourism with footage of Germans gawking at the happenings on the street from atop a tour bus, eager to “party” with beautiful Cuban women; and in an ugly scene of an American tourist with a camera kit around his neck, invading the humble living quarters of a young boy to capture him and his surroundings at will. When the issue of money arises, he declares he’d never give a dime to anyone he’d photographed, because all should be honored he’d chosen them to flatter, or exploit, as it may be.

These personal interactions are fed into a kaleidoscope of evocative short takes: a slow pan through the skeletal infrastructure of an abandoned building beside the wreck of the vintage Hotel Roosevelt (Teddy was the reputed instigator of the trumped up Maine event); a funky ancient typewriter tall as a wedding cake, placed incongruously beside a sparkling new toilet bowl cleaning brush; and in more opaque and impressionistic reverie, silent movie era footage of a man running with wings strapped to his arms; a frame or two of a modern ballet dancer whose flowing white dress billows around her as she turns; and scenes of more contemporary warfare, with bombs exploding like molten rainbows splattered onto the camera lens.

Oona Castilla Chaplin appears towards the end. The actress and granddaughter of Charlie Chaplin (as well as the great granddaughter of Eugene O’Neil) plays a flower child-mother figure to the kids whose numbers have swelled from just Annielys and Leoneli into a near legion. Her garret flat, guitar, and pleasure in enfolding them into her artsy lifestyle is a delightful side bar and adds to the inescapable humanity that pervades the film and the island itself.

The two Chaplins face off awkwardly towards the end. Thanks to a digital sleight of hand, the forlorn Little Tramp peers longingly into the screening room where Oona and the kids are viewing The Great Dictator, 1940,in all his buffoonery. The Little Tramp, the perpetual outsider, stands alone. Caught in a snowstorm, his nose is pressed against the window, watching his grandchild warmed by those around her, and by a burning log fire. This diminutive giant of the “magic machine” contributed the substance and lessons of history to his work, rather than trivialities or hypocrisies for empire or lucre; one can’t help but wonder whether, in choosing Chaplin for this tie-in scene, and watching the children absorbed in his movie, Sauper is crediting them, and their Cuban elders, with seeking enrichment and substance in their entertainment choices, and thus eluding the clutches of the Hollywood ethic.

Ultimately, Epicenter is a quirkily told love letter to a leathery and sophisticated island and a testament to the pluck of its people. It’s a film that challenges us to observe closely and to think hard, while it delivers many moments of pure enjoyment.

Epicenterhas one deficit, however, that is striking. The film doesn’t capture nor engage with Cuba’s primal relationship to music. The soundtrack can be appropriate and atmospheric, especially the Baroque classical interludes and Oona Chaplin’s serenade to the kids, but music is Cuba’s national treasure and source of immense pride. Shared by all, but with its unmistakable African inflection, this legacy is what produces some of the world’s greatest musicians of any genre, it is why the National Ballet from a ragtag country is held up against the Russians, the Americans, the Danish and the Brits. It’s why the world can share the sublime miscegenation that is Latin jazz, and it is what puts that sass in their steps and pride in their eyes that helps keep the marauders at bay.

You can view Epicentro via the Museum of the Moving Image’s website. See below for an interview with Oscar-nominated director Hubert Sauper, talking about Epicentro.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.