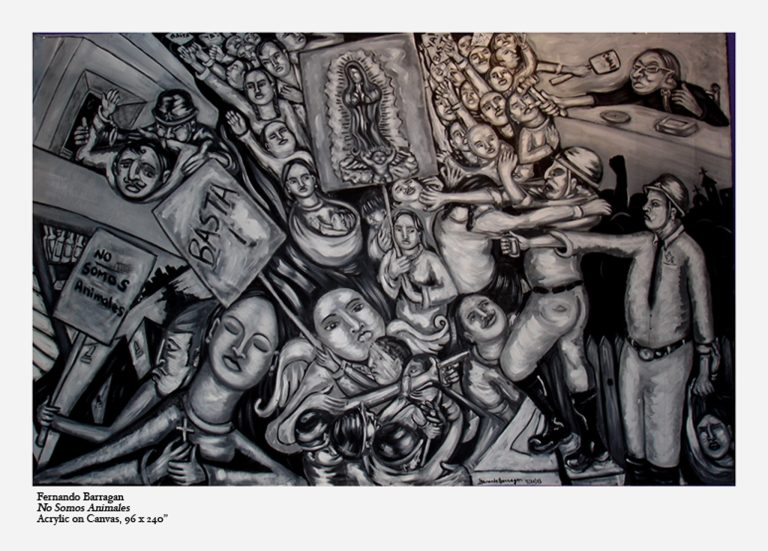

Fernando Barragan’s Chicano ‘Guernica’ Depicts The Violence and Anger of Latinx Communities

11 February, 2022What was an invitation to paint a protest instead became the first “Guernica” manifestation by a Chicano artist. Fernando Barragan’s masterpiece “No Somos Animales” (We Are Not Animals, 2013) is a daring raw canvas mural depicting violence, pain and anger in Chican@/Latin@ communities.

During the opening of Squaring off with Brushstrokes of Paint, Barragan’s solo exhibition at the Jean Deleage Art Gallery at Casa 0101 in Boyle Heights, CA (November 4th, 2021 to February 26, 2022), he was invited by his hosts to step up to the microphone and share a few words about his art. There he stood in front of his monochrome black and white canvas, moving closer to the microphone as everyone waited when his voice began to crack with emotion. His eyes began to water and his voice tied itself in knots. He raised his hand and pointed to the painting behind him, with tears rolling down his cheeks. Choked up with feelings he managed to squeeze out: “This is why I paint!” The tears and the speechless moment became an extension of Barragan’s love, care and concern for his community. It was one of those rare occasions when the emotions transferred on canvas by an artist illicited from its creator a relived memory expressed during the making of the art. It was a collective tear of many expressed and shared by Barragan during that opening night.

In a similar fashion to Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica”, a painted protest against brutal fascist multi-state (Germany and Spain) violence towards a Basque town (Guernica) resisting the Spanish Franco regime dictatorship in 1937, Fernando Barragan took the brush and squared off on canvas with energetic strokes the multiple challenges faced by Latin@/Chican@ communities: police brutality, state and gang violence, discrimination, immigration issues, exploitation and racism. A victim to gang and state violence himself, Barragan carries over the impact on internal family relations and children growing up under such conditions into this artwork. Unlike Picasso’s cubist style of painting, Barragan is closer to Mexican muralist Jose Clemente Orozco’s dramatic figurative work on canvas and walls. Heshares the striking style of Orozco and Picasso’s tragic interpretations of war, despair and inhumane ideologies based on biological classifications and a civilizing norm of violence inherited in modern societies and cultures. Barragan’s canvas mural is a plea to all those involved in the creation of communities, in the deconstruction of alternative humane ways of living, to stop, reflect and catch up with our deepest desire to build healthy environments and find respectful means of understanding ourselves as a community.

“No Somos Animales” depicts a community that could well be interpreted as a scene in Palestine, India, Chiapas, in U.S African American spaces, in Guatemala, in Chile with the Mapuche indigenous people or any other place or space in the world facing violence. Although its interpretation is about a particular Chican@ space, nevertheless it contains a universal conversation. The Chicano “Guernica” in “No Somos Animales”contains the same concerns of those by African artist Dumile Feni’s painting, “African Guernica” (1967): war and its effects. For Feni it was the trauma and devastation of colonial wars on African people and the African continent. For Barragan it is the war waged on Chican@/ Latin@ and immigrant communities by the modern state. When Chicana artists Margaret Garcia reached out to Barragan for an art piece that enacted a protest for a play, Barragan shared in his own words that he “wasn’t going to provide a protest. I was going to give them a riot.” It is a strong timeless political statement made by Barragan towards the powers that be and in particular to individuals. He invites us to examine what is community? How are we building community and who leads these communities? Latin American philosopher Juan Jose Bautista S. reminds us that for the most part modern societies are made of individuals vs. communities. This contradiction between community and individuals is a deep divide towards the collective potential in many communities to resist against the egoistic tendencies embedded in modern neo-liberal cultures, to rescue the collective virtue known as solidarity.

The themes rendered in “No Somos Animales”are made of past and present historical moments: the death of Los Angeles Times Chicano reporter Ruben Salazar in 1970 by sheriffs. Barragan draws from his Mexican heritage of resistance by including in the painting one of the strongest symbols in the western hemisphere, the presence of La Virgen de Guadalupewho led during the early 19th century the people’s political resistance during Mexico’s struggle for independence. It is the same symbol that the anti-imperialist Indigenous rebels, the Zapatistas hold as a banner along with many other icons close to their cause. Scholar Miguel Leon Portilla in Tonantzin Guadalupe: Pensamiento nahuatl y mensaje cristiano en el Nican mopohua describes this powerful indigenous icon Tonantzin Guadalupe (Tonantzin in Nahuatl language translates to our mother) as the most significant fountain of inspiration and Mexican identity. In the canvas La Virgen de Guadalupe is side by side with the Chican@ pueblo. She is not one step behind or one step ahead. She is shoulder to shoulder with the people. “No Somos Animales” does not bypass the theological content. Barragan understands the liberating agency in Tonantzin Guadalupe. Without any doubt it is a matriarch symbol of pueblo, lucha and voluntad. It is in voluntad (will) that the power of the people resides and not in the careerism of Chican@ /Latin@ politicians.

The wall size canvas links Chican@ experiences in U.S. history: the expatriation of hundreds of thousands of Chican@s and Mexican families to Mexico during the great depression (1929-1939); Operation Wetback in 1954 would again repeat the discrimination bias and racist laws towards the removal of Mexicans and Chican@s from U.S. soil. The same can be said of the Japanese American experience during WWII incarceration in internment camps. The painting puts forth the questions: why the continuation of racist policies? Why the continuation of a judicial system that accompanies many historical tragedies of confinement, displacement, and discrimination throughout U.S. history. Why repeat these tragedies?

The epic character in “No Somos Animales”is borderless. The energy and charge in the mural is full of rage. It is Barragan’s cathartic boom; not only aimed at releasing energy, it is a constant volcanic eruption to transcend our given circumstances and make way for positive change. The visual language found in the mural stems from the marginalized mestizo and indigenous working class in Chican@/ Latin@ barrios. What distinguishes Barragan’s work is that he believes in what the pueblo believes in. The footsteps and chants can be heard in the mural from afar. It is a painting that carries sounds and cries.

Barragan challenges the progressive language of visual communications today by painting the life of the community. He does not deviate with this canvas mural to colorful scenes common in urban artwork. He is straight forward. His brushes are first soaked with the pueblo’s sweat and dipped in heart before returning to the canvas. There are no distortions of the human body in “No Somos Animales” as a decadent expression those who have lost hope. Barragan holds on to hope and does not let go. And if he can’t find it, like poet and writer Eduardo Galeano once said, “He goes looking for it.” He does not exclude from his process his intellect or his historical awareness. Barragan amplifies the continental experience of all those familiar with la lucha and la causa!

The reflections in “No Somos Animales”, which I have termed the Chicano “Guernica”, are more than a testimony. It is a philosophical critique in motion that seeks to expose the tools our communities, educators and leaders use to interpret reality which more than often repeats the errors of the past. It is a push to gain ground on a level of consciousness that does not justify exploitation and injustices as the only means of acquiring social mobility.

This essay is dedicated to writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.

Closing Reception for Squaring off With Brushstrokes by Fernando Barragan is February 26, 2022, 6pm to 9pm, at Casa 0101 Theater, Boyle Heights, CA, USA.

Jimmy Centeno is art curator at the Casa 0101 Theater.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.