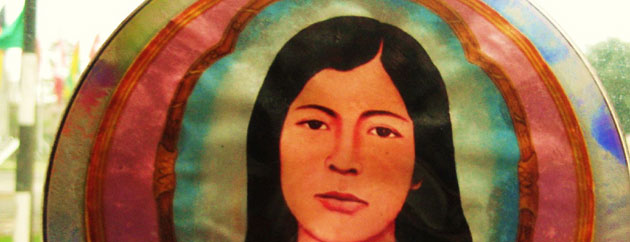

Sarita Colonia, Saint of the People

28 November, 2012Though it’s the most dominant and abundant religion there, Catholicism in Latin America has never been cut and dry. Since the Spanish Conquest, the Christian religion has amalgamated itself to suit the needs and desires of the people over the years. The result is a hybrid with Catholicism at the root: religious practices like the Santeria of Cuba and icons like the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico are but a few of the many religious fusions. For Peru, the short and impoverished life of Sarita Colonia assumes the role as Catholic hybrid and national symbol.

The immense following in Peru that revolves around the unofficial saint stems from the inspirational story of the impoverished Sarita Colonia Zambrano. Born in 1914, Sarita Colonia lived with her three sisters and parents in Huaraz, a small town in the Ancash region of Peru. Little information exists about the girl and her family until 1924, when her mother, Rosalia, fell ill with bronchitis. In order to provide for his family and aid his ailing wife, Sarita Colonia’s father Amadeo moved the family to Lima, in the port of Callao.

For the following four years, Sarita Colonia and her sister Esther attended the Catholic primary school Santa Teresita de Marvillac, which inspired Sarita to dedicate herself to a pious and devout religious following for the rest of her life. Eventually the young girl had to leave her studies to return to Huaraz — the drier climate would suit her mother’s bronchitis better than Callao, according to the doctors. Yet after only four months, Rosalia Zambrano finally succumbed to her sickness, leaving Sarita as the matronly figure for the family.

As the girl cared for her sisters, Amadeo Colonia remarried, giving Sarita three more siblings to look after. With more mouths to feed, Sarita began work at a bakery in Huaraz. But her father decided Sarita could make more money for the family back in Callao, and he arranged for Sarita to live with an Italian family as a maid. For the next three years Sarita Colonia continued to be matriarch and caretaker, just as she was to her own siblings. And when Amadeo became a widower for a second time, he called to his eldest daughter to look after the family once again. He made two trips to bring the rest of his children to Lima, and Sarita left her work as a maid.

Though she had to care for all of her younger siblings, Sarita’s father still needed her to earn money for the family. He spent that year constantly visiting the Hospital Dos de Mayo, leaving Sarita to act as caretaker while simultaneously trying to sell fruits, vegetables, clothes and fish on the streets of Lima. Sarita continued life in such fashion for the next several years, working both at home and on the streets to care for her family, until the age of twenty-six, when malaria took her life in 1940. Her family gave her a modest burial, but with their primary source of care and money gone, Sarita’s family couldn’t even arrange a funeral.

Despite the lack of ceremony in her passing, Sarita Colonia’s story grew over the following decades, seemingly out of nowhere. After her father had posted a cross, name and photo on Sarita’s tombstone, those who knew about her visited her tomb to not only pay respect, but to ask for guidance. As the years passed, the number of visitors grew. Perhaps it was her generosity to her family and to the people, or her strong spiritual will. As with almost all aspects of Sarita’s life, the facts are ambiguous at best. But within the next thirty years, Lima saw a mass influx of the lower classes and indigenous groups of Peru, all coming to the capital in order to find work. Because Sarita Colonia experienced the same shortcomings as many of these travellers, she became a symbol of hope.

Passion and dedication for Sarita Colonia spread, with hundreds coming to pay tribute. During the seventies, the Callao authorities made plans to level off the cemetery in which Sarita resided. Yet their plans never followed through due to the dedication of her followers, who boycotted Callao’s decision until the authorities consented.

Since then, Sarita Colonia’s following has become even more widespread and diverse. What started as a few neighbours and friends paying their respects has turned into a mass movement, which has been called a cult on more than one occasion. Sarita Colonia’s legend began as a guide for the underprivileged who came to find work in the urban sprawl of Lima. Yet over the years, she has become the patron saint for taxi drivers, prostitutes and homosexuals in Peru. The foundation of Sarita Colonia’s sainthood is to essentially act as a guide for the underdogs of Peru — those who are down and out, who have been walked on and ignored. Yet her following has grown so dramatically that even those who are clearly behaving immorally look to her for help, including unfaithful husbands, thieves and murderers.

Despite such a vast number of advocates, the Catholic Church refuses to canonise Sarita Colonia. According to most sources, Sarita cannot be admitted into sainthood because many say that her death was the product of rape, which in the eyes of the church makes her impure. Though medical documentation exists which states that Sarita Colonia died from malaria, many believe that a group of delinquents surrounded her on a cliff in Callao and sexually molested her. As the myth goes, Sarita saw no potential for a happy life after such suffering, and threw herself off of the cliff. Though the story is merely myth, it is nonetheless ironic, since rapists are now part of the canon that considers Sarita Colonia its patron saint.

Regardless of why her followers pray to her, Sarita Colonia is perhaps the most infamous patron saint in Peru, called “The Saint of the People,” or “The Saint of The Town.” Whatever she may be, the people of Peru are forever attached to and guided by Sarita Colonia.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.