S&C Guide to Cumbia 420

13 December, 2021Step outside of a Latin American airport and wait for it… Cumbia 420 will find you before you ask “what is that sound coming from the cars?“. This global phenomenon has its birthplace in Argentina, but let’s not talk about Buenos Aires city aesthetics and lights, for its foundations are located at the very end of the interurban train line, in Greater Buenos Aires, under a different sun and legal jurisdiction, where the wind blows through the trees and night kiosks, and whistles a name from here to Times Square: L-Gante.

With 22 years, a meteoric rise and a flow which has proved universal, Elian Valenzuela (aka L-Gante) is the face of Cumbia 420, the one who’s being heard at every party where a Latin American can ask for a track. To gain a virtual dimension of his reach, according to Spotify, L-Gante alone has 8.5 million monthly listeners, with his most played videos surpassing 200 million views in less than a year. As for Cumbia 420, there are 14 million playlists including at least one track from the genre.

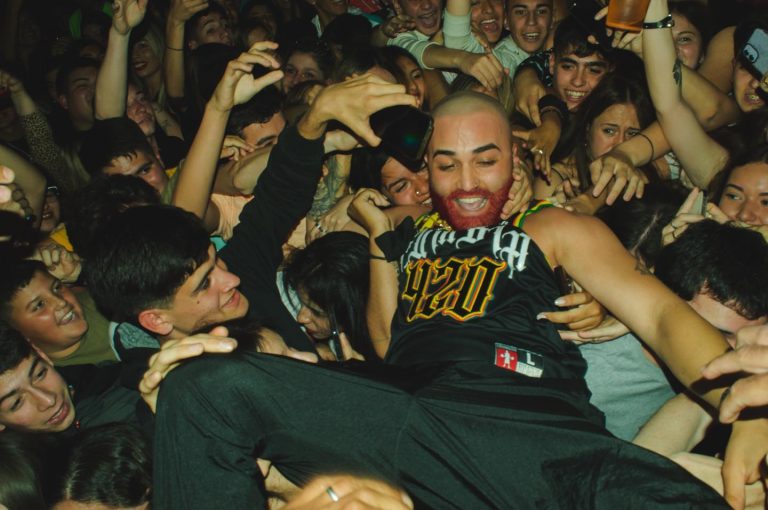

To gain a more physical dimension of the phenomenon it might be useful to mention crowded discos playing Cumbia 420 in every single Argentine city and a recent L-Gante sold out show at Luna Park; plus, in Argentina even children are asking for their favourite Cumbia 420 tracks: when Elian answered the request of a mother whose child knew all his lyrics but couldn’t memorize the alphabet, L-Gante’s version of el abecedario saw him find even more fans.

A genre barely known even 12 months ago, what exactly is Cumbia 420? According to L-Gante’s producer and the musical soul behind the movement, DT.Bilardo: “it’s reggaeton with cumbia villera cadence in its rhythmic structure”. When interviewed by Argentine site El Planteo, he said: “I consider it more a brand than a style. L-Gante told me he wanted [the name] Cumbia 420… [he] was the one who blew it up.”

Along with Bilardo, there’s a whole generation of Cumbia 420 musicians that are rewriting what we know about Latin American culture. And there are many reasons why this is happening right here and right now.

A special land and a special time

The first of those reasons is the everlasting tradition of music produced in Argentina’s barrios. But where do you start explaining? Well, for a start nobody – almost nobody – who visits Argentina stays in the periferic barrios outside the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires [the name for the city of Buenos Aires, autonomous as it has its own jurisdiction].

The river and the highway that separate the Autonomous City from the dozens of cities that make up Greater Buenos Aires [GBA; the collective name for the 24 districts in Buenos Aires province, excluding the Autonomous City] also marks the limit of a lifestyle and, in many cases, a geographical and social origin. It was in GBA where cumbia villera was created and worshiped at the beginning of the millennium. Twenty years later, boys and girls who spent hours every Saturday watching cumbia villera’s flagship program, Pasión De Sábado, are leaving their own mark with cumbia villera as the “frame” in which many, many other rhythms collide.

The key here is that those kids came to this world amid a cultural ecosystem that had gathered music and textures from Argentine regions and neighboring countries for decades. If you went to a public school in GBA, it is very likely that you or your friends came from migrant families from provinces like Corrientes, Santa Fe and beyond. What kind of music was heard in those houses? How did the kids growing up relate to that music? The covers and influences detectable in Cumbia 420 show how deep those layers of music lie in the identity of those kids – today’s artists.

When devices and the Internet started to come to the barrios, slowly but persistently, the youngsters who had grown up with Greater Buenos Aires’ diverse predisposition for music had more and more tools to amplify their musical DNA: reggaeton, hip hop, cumbia colombiana, bachata, Mexican cumbia, and so on. If Greater Buenos Aires was always a socially and demographically different territory, then Cumbia 420 is the proof of how these people from the cities are culturally reacting to the spread of technology. Now it’s time to check out some of Cumbia 420’s main representatives: El Noba, Perro Primo and Tirri La Roca.

El Noba

Believe it or not, I had come to a park in the barrio to finish this piece and was about to start writing Noba’s part when two kids sat just a few meters away from me and started playing… El Noba’s biggest hit (and his latest contribution to the Royal Spanish Academy) “Tamo Chelo”, a video that has hit 9.5 million views in five months, and whose remix is now 6M.

Talking about El Noba means talking about the district of Florencio Varela. And how, how to explain Florencio Varela to those who, even living some minutes away by car, have never set foot in the land where clocks stop when Defensa y Justicia come on to the pitch. Like an island amid the oceanic Greater Buenos Aires – far from its urban centers – Florencio Varela has developed a

particular way of living over decades, and El Noba is the latest outcome of that identity: putting words, idioms, customs of the barrio and many other things, that you’ll only discover by coming here, into a 1:52 song that is relentlessly repeated over and over and over and over through this land. And remember: Don’t drink Chandon les sirve el Federico.

Perro Primo

One of the most beautiful words of Argentinian slang emerged in all its glory when Perro Primo’s last hit “Trucho” appeared on YouTube. In an example of how the meaning of words are constantly evolving in this country, trucho’s meaning has moved from being the name for cheap, low-quality goods you can buy at the feria, to a car, that could even be BMW’s latest model – only that, nobody knows nor asks nor cares where the hell it came from. Perro Primo shares the same musical format as L-Gante, his compañero in Kriterio Music, and could be regarded as the second pilot in the squad leading Cumbia 420. His stats? “Trucho” got 22 million views in two months.

Tirri La Roca

The last time I went to La Plata I heard a man blaming his wife for not letting him baptize their newborn child “Diego Armando”. La Plata, the capital of Buenos Aires province [because, remember, the city of Buenos Aires cannot be capital as it’s autonomous], 60 kilometers southeast of the City, is a big part of “Brócoli”, one of Tirri La Roca’s latest tracks. In the video he says that his combo comes from [Puerto Rican reggaetonero] Hector El Father, but belongs to a place normally ignored by mainstream reggaeton producers. Possessing a similar approach to El Noba, but with a style that is more raw than party, El Tirri is collecting another side of this story that goes beyond the 8M views of his biggest hit: the loyalty of fans that know exactly where he is coming from and how many difficulties he has had to endure to do what he is doing right now.

DT.Bilardo Kevin Rivas

The main creator of beats in this movement took his a.k.a. from 1986 World Cup coach Carlos Salvador Bilardo and the alias is perfectly used: nothing – or almost nothing – in Kevin Rivas’ current success, was left to chance. As he told El Planteo recently, he was looking for a new sound that would both re-start his career as a producer and refresh the language of danceable music in Latin America’s barrios. Once, while recording northern cumbia artist Sebastián Mendoza he realized, accidentally, that he could mix cumbia and reggaeton in a hypnotic way. He mastered the technique, taking inspiration from marijuana culture to define the movement, and share the culture of the audience his artists would be singing to. And one fine day, just as his namesake, he found a young Argentinian star that would take him to glory. With L-Gante alone, he has four tracks with more than 40 million views, with “Perrito Malvado”, featuring cumbia villera heroes Damas Gratis, the most streamed.

L-Gante

Elian’s style matches Bilardo’s sound perfectly and fits like a glove in the global assimilation of cumbia, reggaeton and freestyle. But his main attribute lies in his monster singing skills: the massive rhythmic intuition for vocal melodies and, of course, his unbeatable flow. You can tell this guachín loves music and loves singing and that he has been doing it since a little kid. Among his earliest influences, as he has shown in his videos, there are hours and hours of Argentine cumbia villera, as well as reggae and even rock artists like Pity Alvarez can be heard in his melodies; he has even confirmed that in recent interviews. This combination was already there when, at only 18, he released “Uno Más Uno“, a track that was the hit of 2019’s student parties. Later, once Bilardo’s sound and strategy kicked in, it was only a matter of time. By June 2021 their hit “L-Gante RKT”, named after the remixes created in the suburban bailanta Rescate, was huge in the barrios that created cumbia villera, enjoyed reggaeton and, last but not least, embraced hip hop culture.

When vice president Cristina Kirchner noticed that Elian had recorded the “L-Gante RKT” vocals on a state-issued netbook and mentioned him in a speech, L-Gante’s rise to stardom became inevitable. No matter if you’re around Buenos Aires’ main avenues or in Patagonian villages, you will hear someone playing L-Gante. In the car, in the phone, in one of those portable speakers blasting out at every public get-together in this country. Everywhere.

With this scene kicking off in Argentina, and with Cumbia 420 artists emerging outside of Argentina too, nobody can tell where this is going to take Latin music in the near future. But, two things are certain. One: this has just begun. And two: if you are going to a Latin American city for the first time, now you are ready to join the party.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.