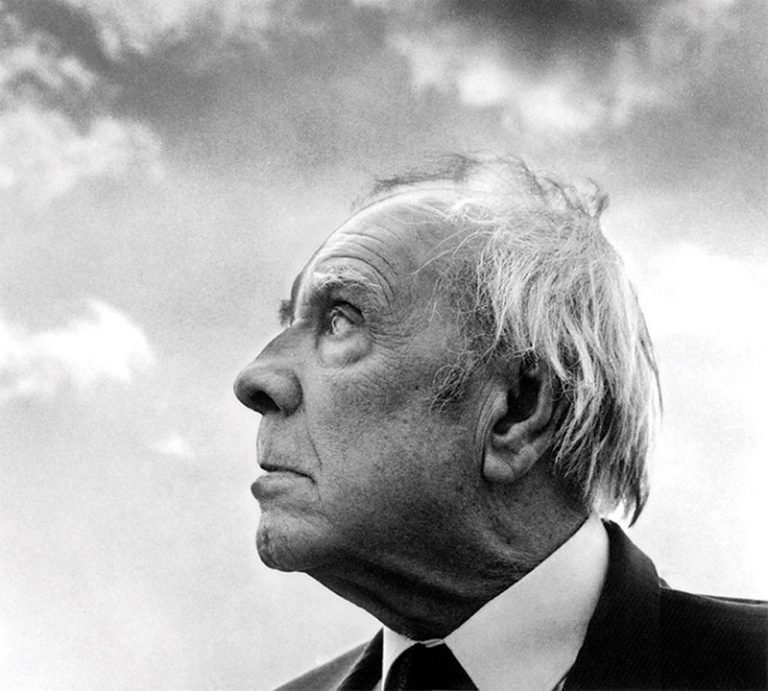

A Small Iridescent Sphere of Brilliance: Describing Jorge Luis Borges

21 June, 2011Some characters present a special difficulty when it comes to portray them: their legacy, their power in the field they master, the respect they command in their colleagues and audience, force the writer to raise the game in order to avoid disastrous comparisons when you are talking about them.

That is the case of a man born with the end of a century in Argentina, brought up amongst armed conflicts and changing times; symbol of literature and focus of international admiration.

Borges – I need not mention his first name (Jorge Luís) because there is no other of whom readers will think – came to the world in 1899 in Buenos Aires. Born to a family traditionally devoted to the national army, his father stood as the clan’s breakthrough into the literary world as a teacher of Psychology and English – he would be the man who made his family wander around Europe right before World War I broke out.

Our man enjoyed his home’s garden from an early age with his paternal grandmother who read English to him until he achieved a proficient level.

At the young age of seven, Borges, instigated by his direct family’s literary surroundings, starts what would be a genius’ production. He begins writing about Greek mythology in English, followed by a fable: The Fateful Visor, which was inspired by The Quixote.

This would be followed by the even more impressive translation of Oscar Wilde’s The Happy Prince, which became his first publication.

It was in the first years of the second decade of the century that his dad, compelled by the drawback of losing his job in Argentina, moved the family to Europe where they covered a fair amount of places before they settled in Geneva when the Great War was declared in 1914.

Personally those would be some of the most nourishing years for this precocious adolescent who swallowed incessantly the European classics. He not only read but also taught himself German with expressionist works; it was Borges that would later translate and introduce some of these works in Spain, which would become his home the year the war ended. There Borges found the chance to read the most talented authors of the country and meet some of the subsequent legends of national literature: Valle Inclán, Juan Ramón Jiménez, Ortega y Gasset, Ramón Gómez de la Serna, Gerardo Diego…

Borges could now only be a writer. And so when he returned to Argentina he embraced the intellectuals of the time and co-funded a couple of magazines, until publishing his first book of poetry: Passion for Buenos Aires in 1923, followed by numerous books of poems and essays.

Arguably, Jorge Luís Borges as we know him was born during the thirties, where he would immerse himself in the literary profession, in the art of being a thinker, in the company of national figures of the size of Bioy Casares and the Ocampo sisters; a friendship that would last for life.

His life would evolve into controversy: man and myth would take different paths in the eyes of many admirers, and politics and literature would later in life interact and cause trouble to an already internationally recognised master.

He continued to translate renowned authors like Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner until in 1938, an accident which nearly cost him his life, did cost him his eyesight. As he got worse he would see his writing skills only limited to dictation, often with the help of his dedicated mother. This did not stop him, however, from publishing Anthology of Fantastic Literature in 1940 and Argentine Poetic Anthology in 1941.

The first problems came along with Peronism in 1945, a regime that would reach an unprecedented peak of popularity. Borges and his mother and sister were part of those who openly opposed to the new political trend, which cost him his job as a librarian. He was made to work as an inspector, from which he eventually resigned and started making a living giving conferences.

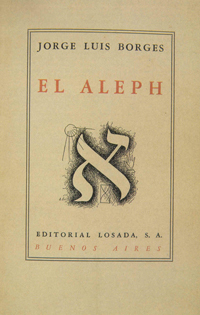

Despite the tough personal times, the end of the decade would bring him his greatest success as a writer, when dictation gave birth to the work which granted him international relevance, prestige and numerous awards and an honorary position within the world of literature: The Aleph (El Aleph – you can read a section from The Aleph in English, Portuguese, Spanish and French on Paulo Coelho’s blog).

This would be considered a landmark in Hispanic literature, and it was certainly a landmark in his life: he was appointed president of the Argentine Society of Writers, an institution supportive of his anti-Peronist views. He would keep publishing until Peronism was over in the mid-50s.

Recognition came in the form of two important positions: he was named director of the National Library and made a member of the Argentine Academy of Letters, alongside an explosion of honorary titles and prizes – including the National Prize for Literature – which reflected the great prestige already enjoyed by the writer.

His professional grandeur seemed to be accompanied by personal joy: Borges married twice, in his 60s and 80s, for the astonishment of his readers, to both a friend from his youth and later, to his ‘guide’, a lot younger than him.

After the failure of his first marriage, where he would require again his mother’s help for writing, in 1974 the winds of Peronism blew back to Buenos Aires, stripping him from his position in the National Library and excluding him from the public sphere.

This would change the image of the writer who became somewhat more controversial in the future for his political orientation than for a few of his works.

As Videla shook the Argentinian political life, Borges, traditionally an opponent to the previous government, pleads alliance to the military junta.

This would cause him rejection by the Swedish board and other intellectual organisations from democratic countries who stated their disappointment – the former declaring that the Nobel Prize was out of his reach.

Some voices argue that it was not so much the support he gave to the new government, but the contentment with the end of Peronism that he showed. It is said that he would even join other intellectuals to enquire about those reported missing in Argentina after the coup d’etat in March 1976.

It would only be in 1979, seven years before his death, when the Miguel de Cervantes Prize was given to him in Spain, a land where he was admired by so many.

Jorge Luís Borges, one the most important ‘pens’ of Hispanic letters and one of the great amongst the greatest in the history of last century’s literature, left us in 1986; a man whose work survived himself, declared by so many other greats as their master, their model, and their example.

Recommended Reading:

Fictions (1944)

The Aleph and Other Stories (1949)

Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings (1962)

The Book Of Imaginary Beings (1967)

The Book of Sand and Shakespeare’s Memory (1975)

Selected Poems

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.