‘Dead Girls’ by Selva Almada: A Chronicle of Femicide

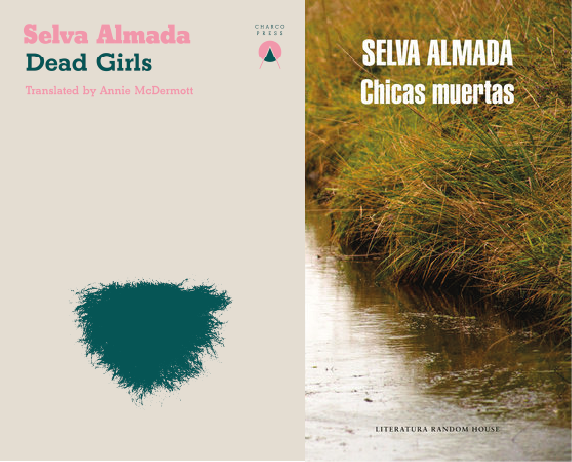

02 October, 2020On November 15, 2012, the Argentinean parliament passed a new law inscribing femicidios (femicides) into the penal code, deeming them to be aggravated homicides which could, given certain conditions, punish the perpetrator with life in prison. Selva Almada’s 2014 non-fictional chronicle, Chicas muertas (published as Dead Girls by Charco Press, 2020), a three-year investigation into the assassination of three female youngsters in the 1980s, reveals the importance of having a legal framework and terminology to discuss gender-based violence. Femicides are regrettably still rampant in Argentinean society, but in the 1980s, as Almada depicts, such violence was naturalised and unchallengeable.

The author of nine books which encompass poetry, short stories, novels, a novella, a compilation of miscellaneous writings, and notes on the production of a film, Almada (1973, Entre Ríos, Argentina) is probably best known for El viento que arrasa (2012) and Ladrilleros (2013). El viento que arrasa was the first of Almada’s novels to be translated into English (by Chris Andrews, published by Charco Press in 2019) as The Wind That Lays Waste, which won the Edinburgh International Book Festival’s 2019 First Book Award. Charco Press, a publishing house based in Edinburgh and founded only recently, aims to translate the best of contemporary Latin American literature and can already boast an impressive repertoire of translations.

For Dead Girls, Almada’s second book to be translated into English, she received public funding from the Beca del Fondo de las Artes to conduct research and carry out interviews on these unresolved murders, which occurred in small towns in the Argentinean interior (the provinces). María Luisa Quevedo was murdered in Chaco age 15 in 1983, Andrea Danne, murdered in Entre Ríos age 19 in 1986, and Sarita Mundín, murdered in Córdoba age 20 in 1988. It is reported that, pending financial backing, the Argentinean production company Murillo Cine will start shooting a TV miniseries inspired by Dead Girls entitled ‘Vertientes del Paraná’.

The chronicle is thus journalistic in nature, although it deploys literary techniques and autobiographical reflections to produce a book which often reads like a novel. The three plots interlace, often in the same chapter, evoking a sense of non-chronological time which is characteristic to fictional narratives. The interviews are reproduced using reported speech, without a clear boundary between the narrator’s interpretation of events and what actually went on the record. The style of the translation by Annie McDermott is sparse and direct, suggesting that the lugubrious subject matter need not be dramatised or sensationalised with literary embellishment. This maximises the effect of the few instances of poetic language, such as the following aphoristic reflection: “Before me stands the cathedral, magnanimous. The further a place from the hand of God, the more imposing the building that honours him” (69).

Dead Girls is not only a chronicle about María Luisa Quevedo, Sarita Mundín and Andrea Danne. Throughout the book Almada reveals the names and stories of countless other young women murdered and often raped by men. Notably, the text captures the endemic and systematic forms of violence which sustain and propitiate a society whereby deaths of women at the hands of men (often whom they knew) became quotidian. In an interview with fellow Argentinean writer Mariana Enríquez for the Edinburgh Book Festival, Almada recounts the painful moment growing up when she realised that violence could erupt from within the home: “Nos habían dicho desde chicas que el peligro estaba fuera de casa” (We were told from a young age that danger was outside the home). Violence need not be physical, as the narrator’s mother tells her:

“My friend’s mum, who never wore make-up because her husband wouldn’t let her. My mother’s college friend, who handed her whole salary over to her husband each month to take care of. The woman who couldn’t see her family because her husband looked down on them. The woman who wasn’t allowed to wear high heels because they were for whores” (39).

Dead Girls doesn’t have the suspense nor the resolution of a detective story as different readers will develop their own interpretations on the cases and their suspects based on the evidence and competing perspectives provided. Instead, it is a careful reconstruction of the broader society where these deaths are allowed to occur. The risks of hitch-hiking (16-18), the girls who are paraded in a beauty contest when they turn fifteen (15), the rotten politics of local male leaders (40), the naturalisation of casual prostitution in rural areas (41), the abuse of working-class women in particular (47), homophobia (61), the corruption of police officers (119), and so on. This is a world of unrestrained machismo, fueled by a political context whereby the value of life was diminished and violence celebrated. In the 1980s Argentina returned to democracy after a brutal military dictatorship (1976-1982) which saw an estimated 30,000 desaparecidos and the widespread stealing of their babies. Whilst gender-based violence extends before and after the political violence of this period, the backdrop is useful to contextualise the fact that the fight for justice over the death of these girls had to compete with the demands of tens of thousands of families of desaparecidos, amid endemic police corruption.

The literary quality of the text shines most when describing the geographical settings. Unlike a novel like Eduardo Sacheri’s La noche de la usina (made into a successful film last year entitled La odisea de los giles / Heroic Losers), a feel-good story which tends to stress the congenial nature of neighbours in Argentinean bucolic towns, Almada’s depiction of Argentina’s provinces is visceral: the decay of the transport network, the sweltering heat of the mid-afternoon slump, being pilloried by gossip, the lack of opportunities and wide socio-economic inequality, all serve to enhance the claustrophobic and forlorn nature of small-town life. It is fitting that Almada’s latest literary experiment, El mono en el remolino (2019), consists of her notes following the filmmaker Lucrecia Martel’s shooting of Zama (2017), as Martel herself masterfully depicted some of these tensions between the capital and the provinces in La ciénaga (2001), set in the blistering summer in the region of Salta.

Almada’s research process also takes her to interview a psychic and tarot reader, ‘La Señora’, devoting several chapters to report on her views after communicating with the dead girls. The value of the interviews with La Señora was the least convincing aspect of the book for me, though it needs to be conceded that psychics were used in the original police investigation and that they remain culturally relevant today in the region. On a bizarre turn of events, an Argentinean senator, María Inés Pilatti Vergara (representing the left-wing party of the Kirchner administrations, Frente para la Victoria) proposed a bill condemning Chicas Muertas, making the outlandish accusation that the book claims justice for the girls should not be sought. The senator’s wild misreading stems from a passage where the narrator interviews La Señora, who reports from the world of the dead saying that one of the girls does not desire revenge.

Claiming that a book like Dead Girls does not pursue justice is a searing indictment on the literary skills of this Argentinean lawmaker. On the contrary, this is a trenchant denunciation of the ways the justice system has failed the victims’ families and the lack of accountability for perpetrators of femicides in Argentina.

Dead Girls is translated by Annie McDermott and published by Charco Press, is available to buy from Hive (UK) or Bookshop (US)

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.