“Juan Domingo Perón Was the Son of an Indian Woman”: An Interview with Hipólito Barreiro

01 November, 2017The former Argentinean ambassador in Liberia and Perón’s doctor, Hipólito Barreiro, is preparing for the reissue of his book Juan Sosa, the Indian who Changed History (Spanish Title: Juancito Sosa, el Indio Que Cambio la Historia). “In Argentina we should recognize that we have a lot of indianhood inside us and give back to the tribes their stolen lands”, he tells me when we meet for this interview.

“You and I are talking because there is something bigger than us that wants me to stay here. Give me your hand and touch here”, says Barreiro as he puts my hand on the right side of his head, where there is a hole. “I have a sinking skull,” he tells me. “I had an accident when I passed a truck coming from Venado Tuerto. I was going to Rosario in a new car. I did not see him coming and I collided. I was in bed for a year, I lost my memory, but I recovered it and I regained retrograde memories too. For at least 50, 55 years I studied Peron. Five nights a week I dream of Peron. I have very vivid dreams where I remember every detail and when I wake up I say: how did I not understand what he wanted to say? What did we talk about? Because we were discussing a lot.”

Barreiro (pictured above) is 87 years old and continues to work in his clinic specialising in the treatment of prostate. Besides his memories, he lives in a department full of wood sculptures – 2,500 in total – that he collected during his years as a doctor and ambassador in Africa and that he plans to present one day in an exhibition. In his free time he works on the reprint of his book Juan Sosa, The Indian who Changed History, about the indigenous origins of Juan Domingo Perón. He had met Perón when he was a candidate for president, then later he treated him as a patient in Spain and remained as a friend of the politician until his death. The book, which was published by Barreiro in 2000 and has now exhausted three editions, was attacked by sectors of the Justicialist Party and defended by Peronist militants at the same time. Even a nephew of Perón polemicized with Barreiro, denying the indigenous origins of the politician’s mother.

Houses

Hipólito Barreiro is a talking book. He quotes from memory entire chapters of his book on Perón and tells me that he is involved in preparing for its reissue, following the release of another book on Perón’s origins: “It happens that when Néstor Kirchner assumed the presidency and passed by the National University of La Matanza, which is national and Peronist, he told the rector: ‘Che, Martinez, we have problems with the birth of Perón. Some say he was born in Roque Perez, others say he was born in Lobos. Take care of this, we can not walk with a dichotomy of this kind with Peron.’ The rector put three professors, two of them emeritus professors, and a third assistant professor, on the job. The two teachers died, but the woman is alive. During the time they worked [on the project] I helped them, I showed them my book and they reviewed my research and made their own. This was published in 2007 and called Perón, When and Where He Was Born?, written by Alberto Gómez Farías, Oscar Domínguez Soler and Liliana Silva. I find that now it is complicated because I have to insert [this book] into my book. It’s very important [this book] because of the discussion around Lobos.”

Juan Perón’s early home in Roque Perez (image courtesy of Historia del Peronismo)

A Tale of Two Towns

Two localities maintain a dispute over the birth of Juan Domingo Perón: Lobos and Roque Perez. In Lobos there is a house recognized as a national museum and in Roque Perez another recognized as National Historical Place. Both municipalities promote guided visits to the buildings, and the streets on which the buildings are located were both renamed after Juan Domingo Perón. Barreiro has made a thorough investigation, providing official documentation and personal testimonies that maintain that the house where Juana Sosa and Mario Tomás Perón lived was located in an area that legally belonged to the Saladillo district. In 1893 it had no church or civil registry, and as Lobos was closer to the address, his birth was recorded in the civil registry of Lobos, since the town of Roque Perez did not yet exist as a municipality. To register in Lobos it was necessary to give an address in Lobos, and hence the confusion.

Sitting in his living room, Barreiro tells the story of the birth of Juan Domingo Perón: “Juana Sosa [pictured below, centre], the mother, was Aónikenk [the name that Tehuelche people use to talk about themselves], but born in the north. She married Mario Tomás Perón, who died of tuberculosis. In the town of Lobos they have a house where they made a museum and they say that Perón was born in that house. Well it should be closed and [those responsible for it] imprisoned. Juan Domingo Perón and his brother Avelino Mario were born in Roque Perez.”

“The father, Mario Tomás, was six years older than Juana. When he was ill, his father Tomás Liberato Perón, who was a doctor, a university professor and had been a deputy, sent him to the house of a friend Dr. Del Marmol, that helped him because there was nobody to treat him in the city. At that moment the option was to go to the mountains of Cordoba, but Cordoba was far and Del Marmol moved Mario Tomás to La Candelaria, a ranch in the pampas of Buenos Aires province to give him a job. As he was young and educated and knew how to read and write, Mario Tomás became a justice of the peace. Juana was taken to look after him, and they fell in love, had two children, and years later they got married. It was not well seen that a judge married an Indian. Mario Tomás bought a field near Río Gallegos, and they moved with the children there, then he got a job and moved to another ranch in Chubut. When Dominga Dutey, who was Uruguayan, asked his son Mario Tomás to marry Juana, they inscribed their children with the paternal surname and Juan Sosa was renamed Juan Domingo Perón, and later Dominga took her grandson to Buenos Aires to study at the military college”.

“Juana helped Mario Tomás a lot. They called Juana ‘egg’, because she travelled great distances to obtain fresh eggs. Perón talked a lot about his maternal grandmother, Mercedes Toledo y Gauna. He loved her very much. She had been born on the outskirts of Azul, near the fort, and was a Mapuche healer, because the Aónikenk and the Mapuche formed a single town there. Curanderas (healers) like her were very important and walked with the armies, the huincas ( the whites), where they would prepare food, take care of wounds and also be used for sex. Then they went to Santiago del Estero and Juana came to Buenos Aires. Perón was born in an indigenous birth practice in the house of his mother. He grew up around nature, first in Roque Perez, where at the age of two a gaucho known as Chino Magallares took him to ride horses without saddle, holding the horse by its hair, and until the age of 11 he lived in Patagonia speaking Mapuzungun. Perón was deeply influenced by his years in Patagonia among Indians. He would later write two books: one on Araucanian toponymy and a dictionary on the Araucanian language”.

Overwhelming Energy

Barreiro interviewed people who knew Juana Sosa in the province of Buenos Aires and in Chubut, where Juana lived until her death. From the testimonies he wrote a profile of the woman who was the mother of Juan Domingo Perón: “She was a woman on horseback, able to do the work of a strong man. The estate where the ranch was set was extensive, about 6,270 square meters, which allowed the family to have a couple of cows for the supply of fresh milk, and also to breed pigs and some other domestic pets for their own consumption, but also for sale, thus solving the expenses of the house. If there’s any doubt of the permanent and untiring work of Juana, especially in those hard years, she soon brought the recognition of a sensitive man like Mario. This became evident to him in the course of time. Little by little the escalation of his poor health would make him more and more dependent on the overwhelming energy of that young Indian.”

“Later in the La Porteña ranch in Chubut, Juana who had inherited from her predecessors certain ‘obstetric arts’ would be an accomplished empirical midwife. They came to look for her from distant places and hundreds of births were her responsibility. It was also said that it was her custom to help known couples, especially if Indian blood was involved. She would encourage them to marry them and give them a few hectares of land and some sheep so that they could live in dignity. Remember that the oldest, Juancito, was breastfed by Juana until he was 5 years old, and it was common to see him behind his mother chasing her with a little stool, to sit next to her and suckle”.

Juana Sosa lived the last years of her long life very close to the Chenque hill, in Comodoro Rivadavia. A chenque, according to the customs of the Aónikenk, are the mounds of earth and stone in which people are buried, and are erected looking east and over hills. The Chenque is the highest hill in Patagonia and eastward it looks at the Atlantic Ocean. There was an indigenous cemetery until the founding of Comodoro Rivadavia, when the Indian cemetery was looted and at the foot of the hill a Catholic cemetery was created. Throughout the 20th century and what goes of the 21st century the municipality of Comodoro Rivadavia has undermined the hill. During the last storm that destroyed the city in March 2017, bones were found that would have been buried in the hill, and had been dragged to the streets by the intense rain. Juana Sosa had a funeral in Comodoro Rivadavia and was buried in Buenos Aires. Juan Domingo Perón shared, once dead, the same scourge as his Aónikenk ancestors: his grave was raped and his human remains mutilated.

You say in the book that the first person who told you that Perón had an indigenous family was singer Aimé Paine.

“Yes. I met Aimé Paine in Santa Fe. I am from Rafaela, a town nearby, I was struck by how beautiful and intelligent she was. She was a lawyer, and was in a major hotel in the city. We met by chance, she had gone to give a conference in the municipal theatre of Santa Fe and we became friends very soon, I took the photo of her that I put in the book.”

“We started talking and I said, ‘you know a very important famous person inside the Mapuches’. ‘Of course, she told me’. I wanted to surprise her, but she already knew. She encouraged me to tell the story.”

In his book Barreiro says: “From her lips I heard the revelation of something that until that moment I had ignored and that left me stupefied: Juan Domingo Perón had Tehuelche blood. She added that when the general returned to the country for the first time from exile in 1972, and newspapers began to publish his latest photograph, as an old man in his 80s and after 18 years of absence, his older aunts exclaimed: ‘Look, look at it … It’s RE-CHE.’ ‘Che’ in Mapuche is ‘Persona’ and ‘Re’ means ‘to be well marked’. With that the aunts wanted to mean that the General looked more Mapuche than ever.”

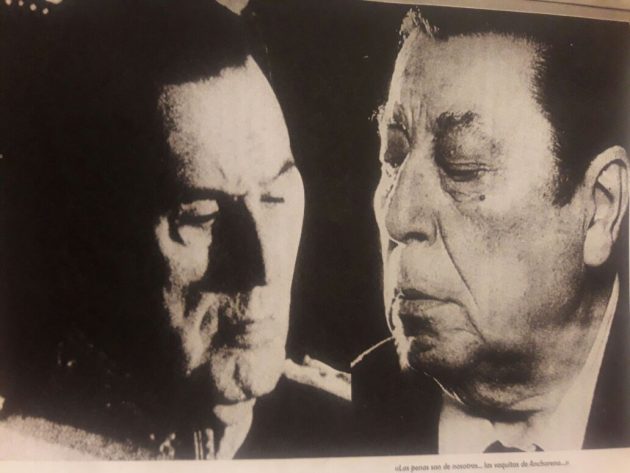

“In fact, these anthropological features are well-known. They are accentuated by the advanced age when the Mapuche man enters the final stage of his biological cycle. I could not find scientific explanation of this fact, despite the sources of anthropology consulted. But the truth is that I opted for the practical and compared the photograph of Perón with a known character of folk music: Atahualpa Yupanqui, a Tehuelche Araucano born in the south of Pergamino, in the province of Buenos Aires. The facial features of both men (see the comparison below) tell us that although they are different people, they respond to the same anthropological pattern.”

Long before Argentina existed as a country the Moluches and Huilliches passed to this side of the Andes, through the vuriloches, the only ones who knew the passages, that possibly San Martin also used to make the crossing. They mixed with the Aónikenk and the Rankülches, Mapuche people today is the result of that mix”.

On the Way of Tears

Barreiro describes the uprooting of indigenous peoples from their natural habitat to contextualize the events that marked the life of the family tree of Juan Domingo Perón: “In the 19th century as a consequence of the military campaign against the Indians that was carried out by General Julio A. Roca, we proceeded to uproot the Mapuche Tehuelche ethnic groups, from the Valcheta area in the lower Río Negro, and carried on foot to the Tucumán. Although arguing for security reasons, the real reason was another: get slave labour for the collection of sugar cane. They say that it was a forced and tragic march and that many men, women and children died in the long road that was known in Indian history as “the way of tears”. Others more fortunate escaped and knew to return to their beloved ‘NELFUN-MAPU’, that was the land of the flat fields or simply La Pampa. “But the rest were prisoners, slaves of the huinca who owned the cane fields, or dispersed in the neighbouring provinces where the Indian, Diaguita Calchaquí, lived. Even today the descendants of those ignore their true identity and although they speak the language Diaguita, they wonder how their Mapuche / Tehuelche ancestors could reach so far north from “the country of icy winds.” This must have been the fate of many like Juan Ireneo Sosa, Juana’s father, who although he was born in Santiago del Estero had Tehuelche blood.

Perón Talks about his Indian Blood

In December 1967, the magazine Siete Días Ilustrados published an interview by journalist Adriana Civitta with Juan Domingo Perón in Spain. The article was capped with the title “When I can return”, and four pages inside with the headline: “I was born to command”. The former president told the journalist his indigenous origins: “I belong to a middle-class family. Of the normal type of those times. My father had a ranch in the town of Lobos. There, my dear, I was born … At that time Patagonia began to develop and there were very few people yet. My father, who had been a medical student – my grandfather had made him study, a little by force – went to the country when my grandfather died. To the home in Lobos … Then he sold all that and with the profits he bought a field in Patagonia. In 1905 he sent me there …”

“And there I was. In Rio Gallegos! 38º below zero! So I grew up in the harsh environment of Patagonia. Of course, you understand me… the age came when a teacher over there could not teach me much. That’s when I came to Buenos Aires. Ah, what solitude in Buenos Aires! I lived totally alone. I was in the International Polytechnic College… What solitude, it was a boarding school, you know? First in the Buenos Aires City and then in Olivos. I was there until the age of 15, at which age I entered the Military College, and remained in the College for the years established by the Military Regulation … But like all things, my life has had a beginning. The leading light has been my mother. She descended from the Spaniards: Toledo Sosa. They were fourth-generation Argentines. My grandmother told me – I still remember vividly – that when Lobos was just a fort, they were already there. When the old woman used to report that she had been a captive of the Indians, I would ask her: “So, grandmother … do I have Indian blood?” I liked the idea, you know? And I think I actually have some Indian blood… Look at me: salient cheekbones, abundant hair… Anyway, I possess the Indian strain.”

“And I am proud of my Indian origin, because I believe that the best in the world is in the humble. I do not believe in the evolved. The world has only good men and bad men. They are the only categories I accept. The more evolved man can become more perverse than the humble, because the more intelligence the human being has, the more economic and cultural means he enjoys… the more danger he can bring to his fellow man. Now, you will wonder about my father. My father was not humble. My paternal grandfather was a doctor of the Argentine oligarchy, he was famous. Deputy, senator, president of the National Council of Hygiene, Army Senior Practitioner in Paraguay… He was a man of excellent economic position … He contrasted with my mother, whose only fortune consisted of her Lobos butcher shop. My grandfather was respectable. He was a rancher, and my father too… I repeat: for me the best [thing that] the countries have are its people. Everything else, my dear, is divided into two categories: good and bad.”

Dr. Puigvert, who operated on Perón in Barcelona, recounts in his memoir My Life … and Others (1981), that the general told him in 1964 that he had two years more than what appeared in the papers; and when, surprised by the blackness of his hair, he asked if it was dyed, Perón replied: “Never, I have a lot of Indian blood in my veins. Total, from my mom. In this race, the white hair is very rare “.

Recognition

Barreiro lists a score of laws and measures ordered by Perón that “are forming the legal body to ensure the progressive and irreversible improvement of the Argentine aboriginal”, among others the creation of the commission and the worker’s statute, with which it was tried to put an end to the exploitation of rural workers. The author contends that Perón was “a man with destiny,” and points out that his way of exercising leadership was typical of the qualities of a cacique [Indian chief]. He enumerates and documents Perón’s sporting achievements within the army: instructor of basketball, boxing, high jump, shot put, calisthenics, fencing champion. And he declares: “Perón inherits from his aboriginal mother the Indian instinct of telluric perception, the indomitable spirit of the desert, and the cacique‘s wisdom in imparting justice … but also the love of the earth (Mapu) and the humanism of the people that grows up with the stars as their roof. The combination of all these attributes, because Peron was all that, explains his charisma and his spirit without equal. That is why simple people understood and loved him. And although he received the contempt of those barons to whom he ‘touched the pocket’, he was followed by his dispossessed people, because he had touched their hearts.”

Was Juan Domingo Perón the most important indigenous person in Argentine political history?

“I am godson of Hipolito Yrigoyen. He baptized me in the church of San Agustín on Las Heras street as he was a friend of my father, who had indigenous blood. Juan Manuel de Rosas too. To make a short list: our great hero, José de San Martín. Do you know whose son he was? San Martin was a stolen Indian child. He was born in Yapeyú in the house of the San Martín’s who were representatives of the king of Spain. They were here four or five years and then they returned. They had a Guaraní maid, and at that time a guest arrived to their house, Carlos Maria de Alvear. At night he was served by the maid and she made him a son. That son was born and stayed with the guest. They promised the maid they were going to send her to fetch him, fix it, [but] what shitty people. Someday you will know, San Martin was an Indian and if he had not had that heart he would not have proceeded as he did, he would not have spoken to Simón Bolívar as he spoke. He criticized him and I have the letter he wrote to him after the meeting in Guayaquil. Justo José de Urquiza [also] had 200 children, or at least the children that were counted, so there you could say we have a lot of Indians [here] and we have to recognize it.”

How do you think the Argentine State could recognize the native peoples?

“What it would have to do, politically, is to remove the statue of Roca and his horse, defenestrate everything that is named after Roca, have him return the properties that he stole starting with the Military Circle that was of the Paz family and that the money from those properties be returned and placed in the bank accounts of our indigenous tribes.”

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.