‘The Adventures of China Iron’ Charts Alternative Histories, Polyamorous Adventures and Argentina’s Lush Landscapes

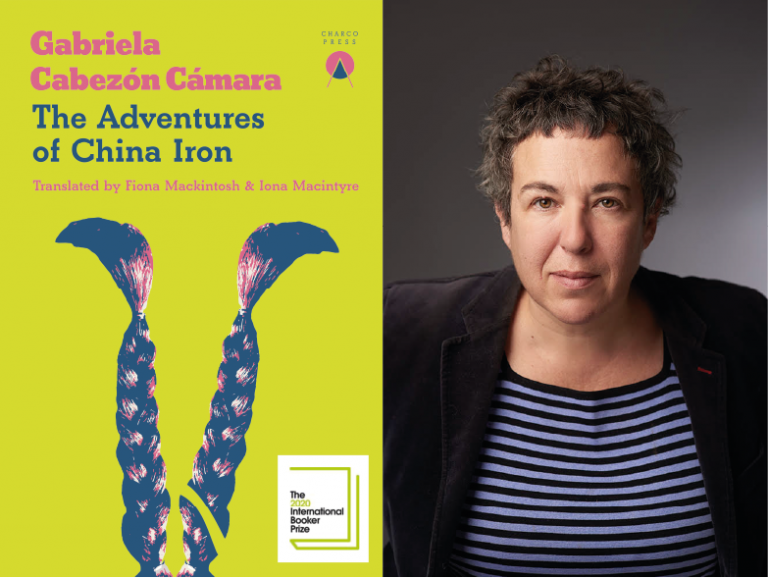

11 August, 2020Gabriela Cabezón Cámara is one of the leading figures in Argentinian literature and a prominent feminist intellectual. The Adventures of China Iron is published by Charco Press and translated by Iona Macintyre and Fiona Mackintosh.

The Adventures of China Iron charts the travels of the character China Iron [publisher’s note: pronounced ‘cheena’: designation for female, from the Quechua] across the pampas of Argentina in a covered wagon after her gaucho husband is conscripted. If that sounds like a simple, linear experience, it’s not: in a brilliantly original slant, China’s husband, Martín Fierro, is the same one described in the famous epic poem El Gaucho de Martín Fierro by José Hernández which is re-imagined to afford China a life of her own. Oh, and China and her Scottish companion Liz become fast friends, then fast and furious lovers.

Attempting to describe the book in a few sentences reiterates that there probably has never been a more apt title of “Adventures”. There is so much packed into a raucous, outrageous set-up, simultaneously bittersweet and endearing. China absorbs everything wide-eyed with all the vigour of someone seizing life with their entire being for the first time.

The book is in three parts but contains a myriad of complex themes. As a tribute to its tripartite structure, I have picked my three favourites:

An alternative history

China’s story is an ‘alternative history’ in a few ways. She comes from several layers of disadvantage; she was born illegitimate, “a black woman’s slave for half [my] young life” then married and the mother of two children by the age of 14. This, woven through the narrative, really gave me a portrayal of intersectionality that is so important. She is a wildly attractive and fun character. China was subordinated by marriage to Fierro, who himself spent time at Campo Malo, the fort owned by José Hernández, which China and Liz pass through on their journey into indigenous territories. Fierro’s song, in a metric-verse chapter titled “Oh China, Love, Forgive me Now”, quotes some stanzas verbatim from Hernández’s original epic poem but rewrites the narrative. It is worth its own prize for Gabriela Cabezón Cámara and her translators. It poses an interesting question: do you ‘rewrite’ history if you give historically-oppressed characters a voice, and reevaluate a celebrated figure?

Exploration

The publisher Charco Press describes China Iron as a “riotous romp”. As well as the journey itself, adventures and romping are expressed through exploration of gender and sexuality. Both in the wagon and at the fort, China’s raw sexual awakening juxtaposes naivete with curiosity and depictions are frank without shame. Boundaries are constantly and intriguingly blurred. In the final third of the novel, no longer beholden to any restrictive social norms, China “learns to fly” and reaches a state of fantastical glory: unhinged, polyamorous, one not described adequately by any single label. It becomes a defining part of her new lifestyle.

The lush Argentinian landscape

I couldn’t review this novel and fail to mention the exceptional treat the reader is given with visions of the Argentinian landscape formed from lyrical descriptions, for example:

“The land gets muddier and muddier until it gives way to the croaks and cheeps of a reed bed, the air on the banks sings with the criss-crossing of guyrá in flight, riverbanks a little luxury the pampa allows itself, the cows bathe with a little persuasion, slipping and slithering; the land then re-emerges from beneath the river, and although it must be the same land, it’s now full of trees, their naked roots at the water’s edge.”

I see, in the closing note by the translators, that there was reasonable challenge translating these sections given many of the species of flora and fauna described in the novel do not have their own English names. It was enough, in any case, to pique my curiosity and it was a mesmerising exercise. My personal favourite was the mburucuya (go on, search it, you won’t regret it).

I really recommend The Adventures of China Iron for a fantastic journey, wonderful themes and a stunning translation ringing through the entire work.

The Adventures of China Iron is available to purchase from Charco Press or via Hive. The novel was shortlisted for the 2020 International Man Booker Prize and you can watch an interview with the author and the translators here.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.