The Magic Of Comics Is In The Language: An Interview With Lucas Varela

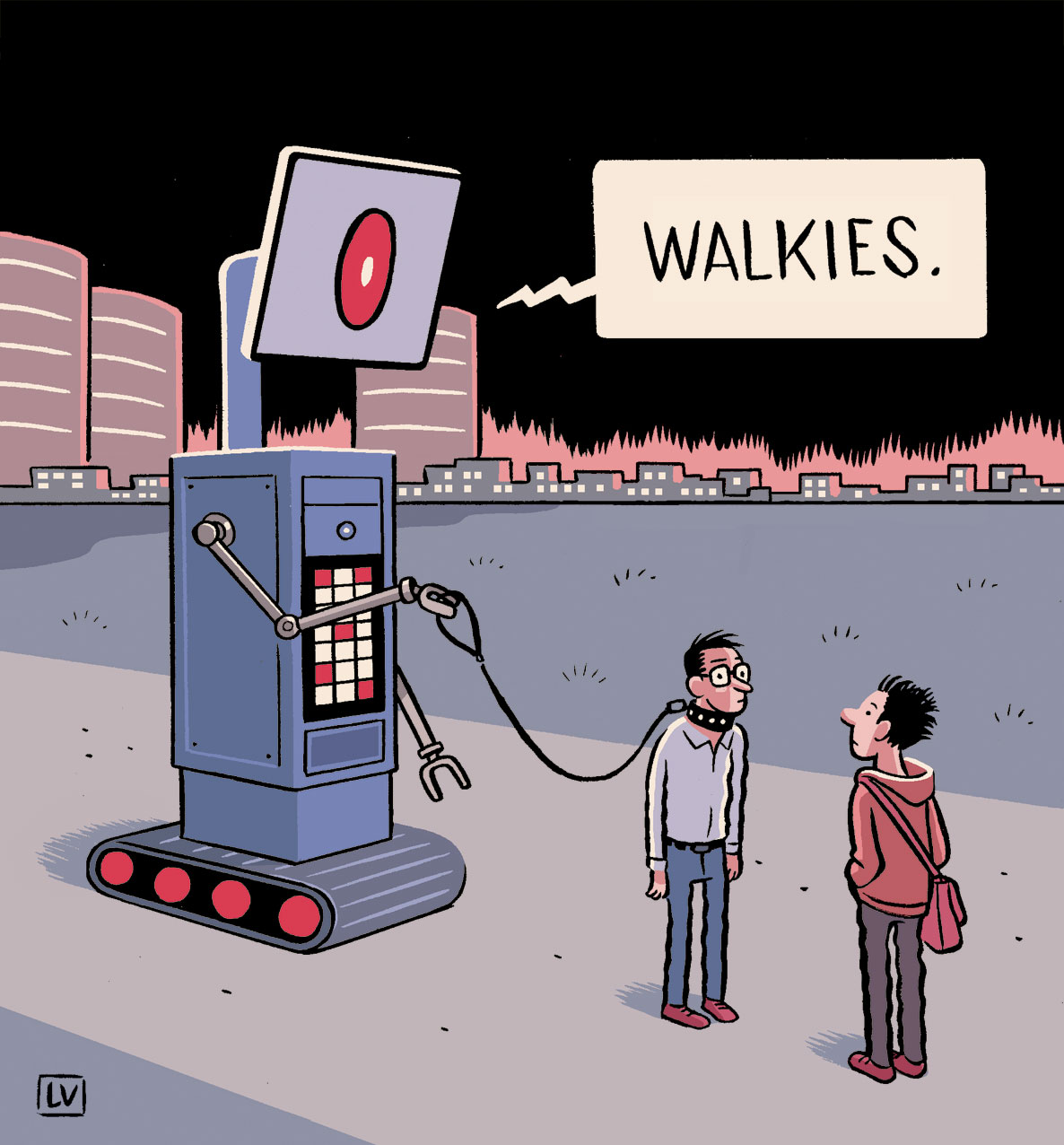

04 December, 2014When I asked Lucas Varela how he would describe his own work, he said: “I tend to think that my style is of clear lines and an underground spirit; sinisterly silly, pink, rotten, and dismally friendly.” However, he adds, “that’s how I wish it were, but most of the times, it’s just silly.”

No matter how he describes it, Varela’s style – witty and irreverent – is one of the most recognisable in Argentina. Known to British readers mostly as an illustrator of a column in the Financial Times, Varela’s interests span various artistic genres: he’s also a graphic designer, a cartoonist and a comic book author.

Born in 1971 into a family of European heritage – his mother a teacher, his father a businessman – Varela grew up reading comic books like Skorpio and Fierro, just like every other Argentinian kid. His interests evolved and he became inspired by great Latin American artists like Alberto Breccia, Horacio Altuna, Domingo Roberto Mandrafina and Enrique Alcatena.

After completing a degree in graphic design at the University of Buenos Aires, Varela began working in design studios, eventually getting a position at the Argentinian magazine Clarín in 1996, but it soon proved to not be enough. “One day I got tired of graphic design, and I focused on the area of editorial illustration”, Varela says. “At the same time, I was publishing fanzines about comics, popular among the Buenos Aires underground.”

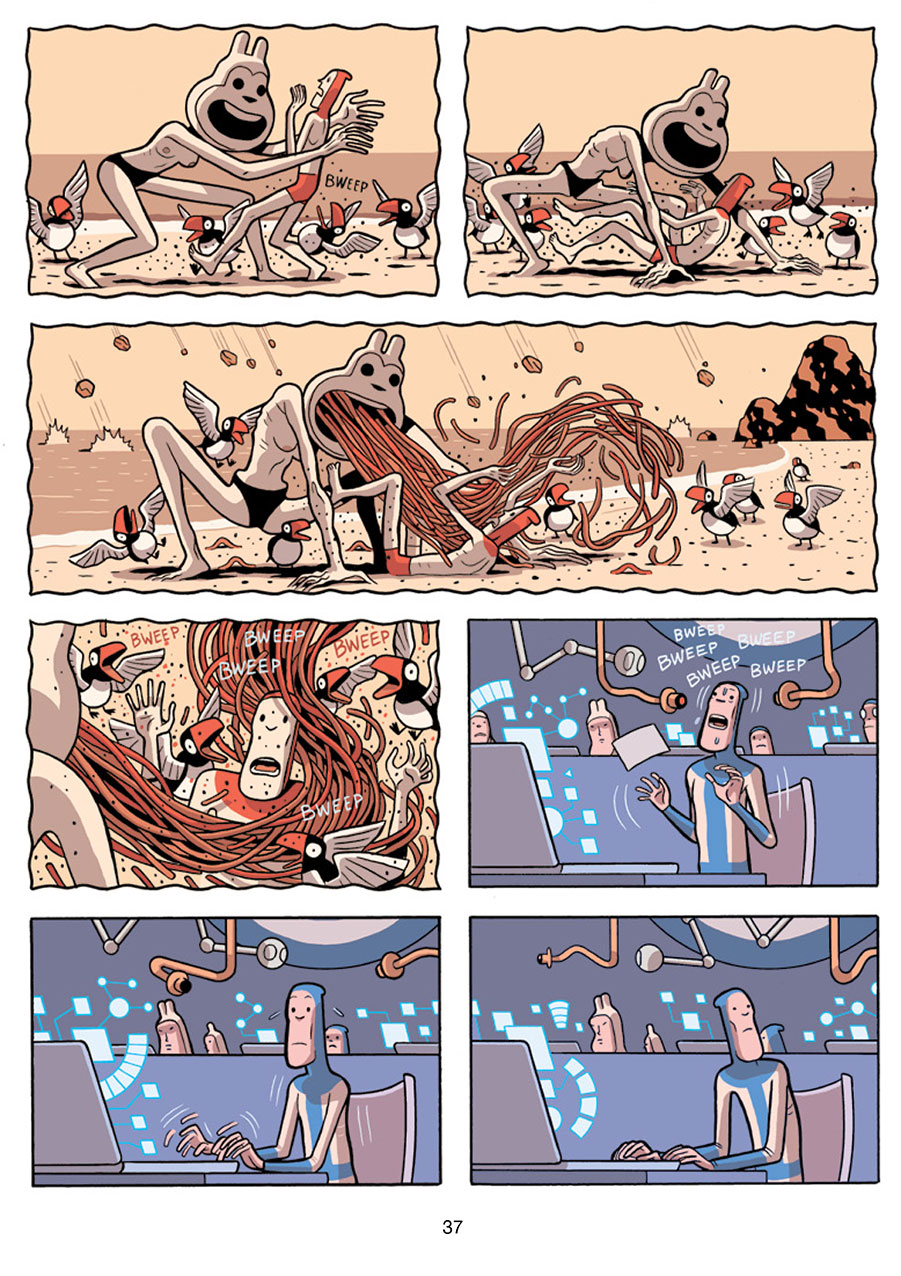

Varela’s style can still be easily traced back to the mischievous aesthetics of underground comic books. Strong, firm lines, simplified shapes and colour-block shading may invite comparisons with cartoons and child-like illustrations. But there’s much more – Varela adds to all some chaotic yet ornamental abundance, cheeky close-ups and saturated colours – resulting in an autonomous universe of the artist’s ambiguous vocabulary.

“One may claim that there’s some connection between comics and illustration in my work regarding the form. But there isn’t one ‘comic style'”, he declares. Balancing the style of illustration and comics emphasises the impossibility of separating these two genres precisely. “All those mysteries and subtleties attract me a lot”, the artist admits.

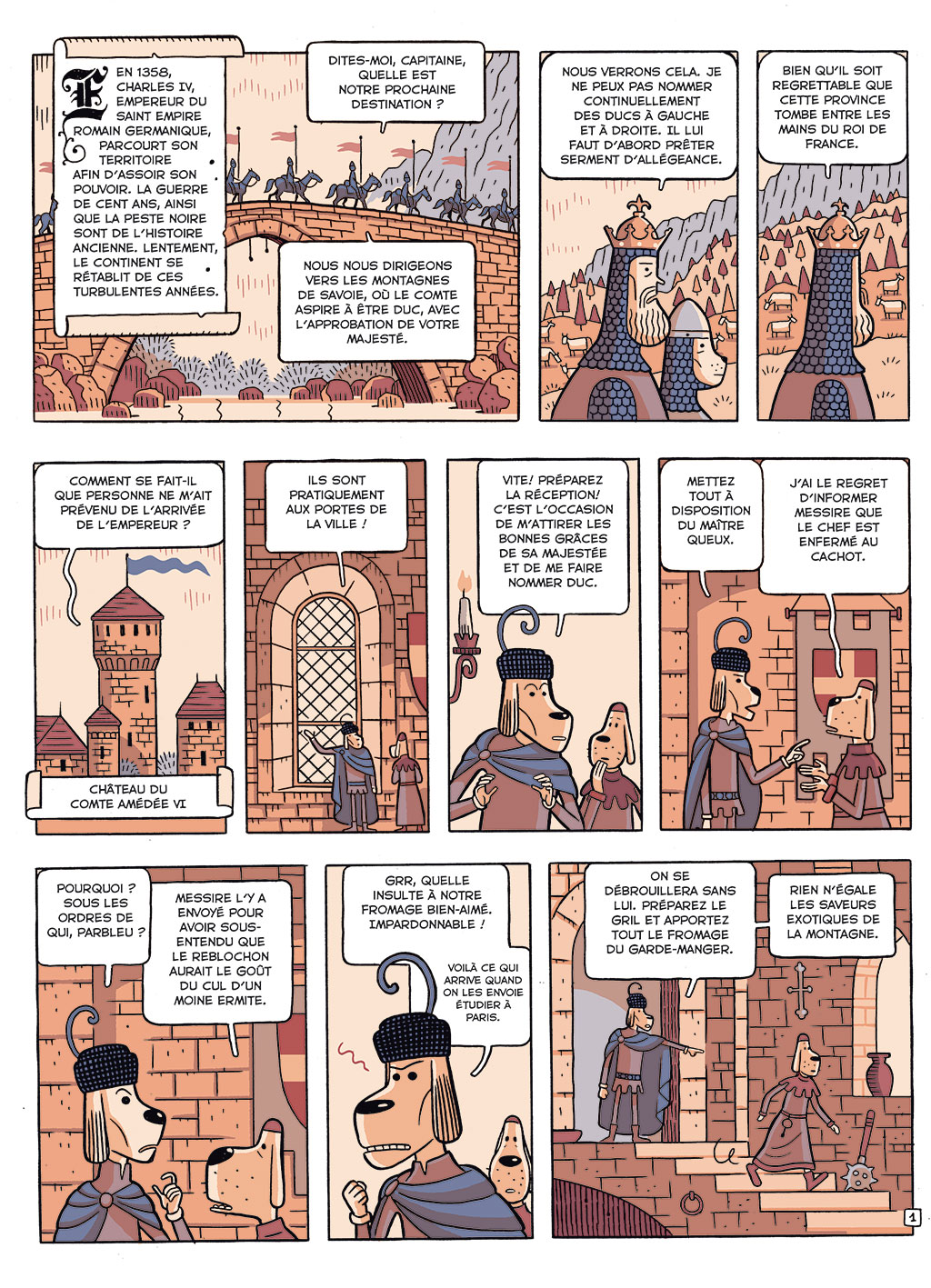

Varela illustrated two collections of short stories Estupefacto (2007) and Matabicho (2009), following them with La Herencia Del Coronel, which was based on a script by Carlos Trillo and later included in the Official Selection of the Festival of Angouleme in 2009. Two years later, he published Paolo Pinocchio, of which he was the sole author. The story, based on the classic Carlo Collodi tale, is a cynical, black-humoured variation on the adventures of a wooden boy – Varela’s Pinocchio finds himself in hell.

“I think that the magic of comics is in the language, and until now, no one has been able to define it quite exactly”, he says, recommending Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, as a good attempt at explaining the science of comics and graphic novels. The crucial quality of the genre is that it is a fusion of words and images, but it has its own autonomous language, with the drawn lines being its words.

Considering Varela’s experience in the underground world of Argentinian comics, it might seem risky that in 2010 the artist was chosen to be an illustrator for National Conversation, Robert Shrimsley’s weekly satirical column in the prestigious Financial Times. He has continued this assignment ever since. Varela’s rebellious, apparently inadequate style and witty illustrations provide a refreshing, ironic outlook.

When asked about the creative process of an assignment, Varela says he tends to reject the most desperate illustrations that appear first in his notebook. Working quickly matters a lot, he adds, and “if it’s pretty or not – it’s of secondary importance.”

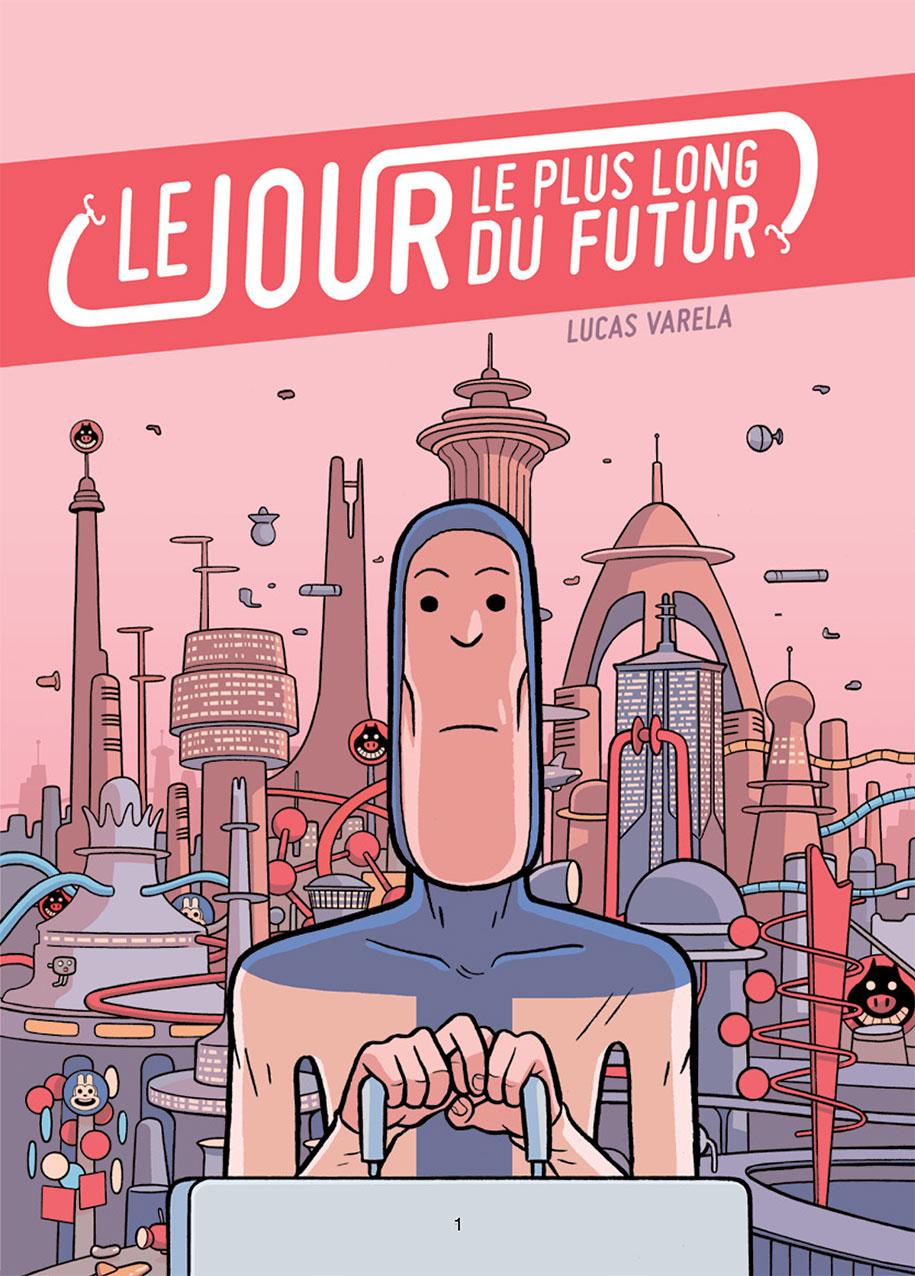

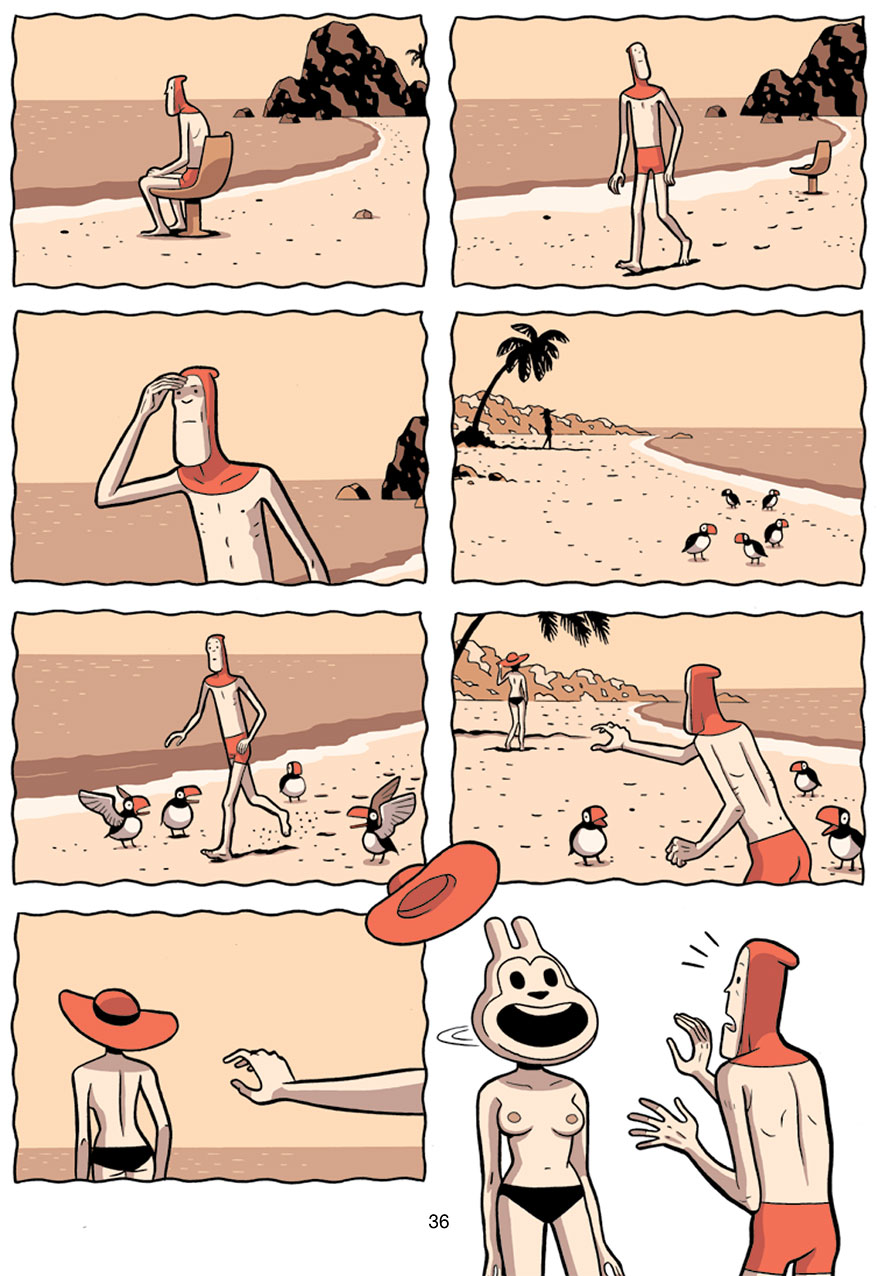

However, the rules of fast work and approaching deadlines do not quite apply in the world of comics. These days, Varela is applying the finishing touches to a graphic novel Le Jour Le Plus Long Du Futur (The Longest Day of the Future) that he describes as “the longest story I have ever written.” He has been working on the project for several years, alongside several other artists, as part of a residency in Angouleme, France to develop independent comics. It might serve as an excellent illustration of studies on the form: it’s an entirely mute graphic novel, “inspired by the pioneering comic books of the early twentieth century”, with its narrative built exclusively by illustrations. Le Jour will be published in 2015 by Delcourt, and will – probably – be the best evidence to finally show that the twisted, pink, silly lines do speak, and they do it well.

You can see some exclusive never-before-seen images from Le Jour Le Plus Long Du Futur below:

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.