The Murky Origins of ‘La Balsa’, Argentine Rock’s Big Unveiling

23 January, 2020At a time when most bands in the region were either releasing Beatles covers or penning their own material in English, “La Balsa”, one of the first Spanish-written rock songs, is widely considered rock nacional‘s [the term used in Argentina for homegrown rock] big bang moment, galvanizing the scene overnight and inspiring generations of musicians to come.

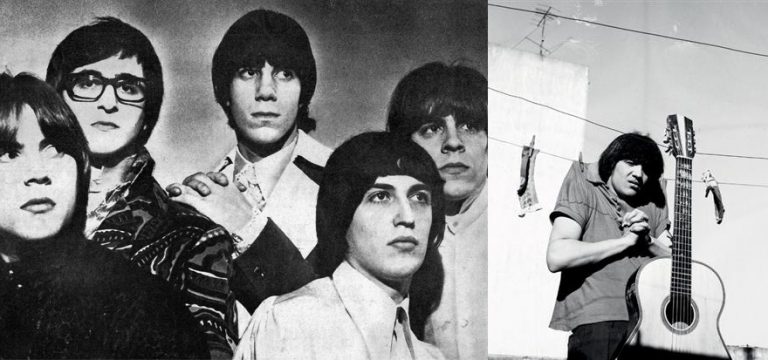

Despite this undoubted influence, the origins of “La Balsa” remain a contentious point. Its beginnings can be traced back to dawn on May 2 1967, when José Alberto Iglesias invited Litto Nebbia to the bathroom of a Buenos Aires bar, La Perla de Once, to play the outline of what would later become “La Balsa”. From here the story muddies, as Nebbia’s band, Los Gatos, released it as a single on July 3, with Iglesias’ role limited to a co-author credit (as Ramses, one of his many aliases).

Los Gatos, a psychedelic five piece, are considered one of the founding fathers of rock music in Argentina, along with Almendra and Manal. Their swinging, blues-rooted recording of “La Balsa” resembles the Doors, particularly in its meandering keyboard solo, and would go on to shift 250,000 copies. At a time where bands of a similar pedigree struggled to break the 5,000 mark, “La Balsa” was a runaway success and ignited the movement instantaneously. The band followed up on their newfound fame with the release of their debut album, Los Gatos I, in November 1967, which was credited entirely to Nebbia, save for “La Balsa” and “Ayer Nomas”, a b-side to “La Balsa”, written by Mauricio “Moris” Birabent and Pipo Lernoud.

In the years that followed, Nebbia would insist he was responsible for composing the majority of the hit, describing Iglesias’ involvement as being limited to just the opening line “Estoy muy solo y triste acá en este mundo de mierda” (“I am alone and sad in this world of shit”), which would eventually be reworked in the final version. This account has largely remained uncontested, though this is in no small part due to the untimely death of Iglesias in May 1972 at the age of 26.

Iglesias’ body was found by the San Martín railway line close to Palermo station. His death was unreported and uninvestigated, and while tragic, unsurprising. Since the late 1960s, his mental health, hastened by habitual intravenous amphetamine use, had deteriorated to the extent that he was repeatedly incarcerated and institutionalized, and often subjected to electroshock treatment. This decline culminated when he was transferred to a criminal psychiatric unit. It is believed that he escaped from this facility on the morning of his death, falling from the train on his way to his mother’s house in Caseros, a suburb on the outer edge of Buenos Aires.

The following year, Tango, a posthumous collection of songs that Iglesias had recorded in 1970 was released, under what has become his most definitive pseudonym, Tanguito, a name that even today holds almost mythical clout. Given the circumstances, it is unsurprising that this is a raw and earthy record, largely centred around an acoustic guitar and a lone voice. Throughout Tango, Iglesias shows a masterful knack for finding the sweet spot between genuine tenderness and bristling nihilism. This blend is most apparent on one of the standout tracks, “Amor de Primavera”, a crackling lullaby which, while written by Hernán Pújo, owes much to Iglesias’ pained delivery. This desperation reaches a highpoint in the Kurt Cobain-esque wounded coo-ing that accompanies “El Despertar de un Refugio Atómico”.

There can be no discussion about the version of “La Balsa” which appears on Tango without first mentioning its prelude, which not so much stokes the flames of controversy, as pours gasoline over them. In a thirty second opening snippet, the voice of Javier Martínez, drummer with Manal, repeatedly insists that Iglesias “composed La Balsa in the toilets of La Perla de Once”. Martinez would later attempt to play this down, claiming his words had been taken out of context, and he had not wished to imply that Iglesias was the sole author of “La Balsa”. Nevertheless, the impact of this outtake still resonates.

Listening to this bleak and stripped-back interpretation, it is easy to understand why there are so many conflicting opinions over the song’s fundamental meaning. Nebbia has repeated on numerous occasions that Los Gatos’ breezy rendition is one of hope, while aficionados of Iglesias’ work struggle to ignore the references to drugs amongst its more haunted tones.

With time, Iglesias’ flame flatlined as recognition became limited to niche circles, while artists who had been inspired by “La Balsa” reached superstardom. This changed in the nineties following Tango Feroz (1993), a Marcelo Piñeyro-directed cinematic release which taps into the mythology surrounding the ill-fated songwriter. While the film was responsible for a resurgence in popularity for Iglesias, it is a frustratingly anaemic portrayal that eschews a genuinely otherworldly figure in favour of an insufferable boy wonder who mopes around Buenos Aires strumming paeans for a girl whose love, he repeatedly insists without irony, will bring him immortality.

As is so often the case, the thirst for a binary, definitive debate over the origins of La Balsa is ultimately pointless. This clamour has often done a disservice to Nebbia, as those seduced by the ethereal nature of the Iglesias legend, willfully ignore a rich and storied career to suggest underhandedness on the part of Los Gatos singer. A commemorative plaque outside La Perla de Once strikes the right balance, celebrating the importance of both in the birth of rock nacional. Once frequented by Jorge Luis Borges, this popular hotspot for rising musical talent suffered a downturn in fortunes leading to its closure in January 2017, following the likes of CBGBs and the Hacienda as a cultural site falling victim to the world’s spreadsheet jockeys. Despite this sad demise, the legacy of La Perla de Once, like that of “La Balsa”, remains as a cornerstone of Argentinean rock nacional.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.