A Shared Struggle: The Roots of Reggae in Brazil

09 June, 2020It’s a sweaty Sunday evening in São Paulo, Brazil. The karaoke club I’m in plays carnival classics and MPB hits from today. That, I expected. But after every three or four songs, my ears perk up to a familiar reggae bass line. Reggae hits like “Could You Be Loved” and “I Can See Clearly Now” are being performed alongside Brazilian artists who play reggae in Portuguese. After an eye opening conversation with my friend/host, I learn that reggae music and culture has been embraced into the roster of mainstream Brazilian musical genres. Popular reggae artists, like Alexandre Carlo of Natiruts, have international followings and canonical hits. Upon first glance, reggae in Brazil seems ubiquitous. But its cross cultural beginnings tell a story of how the alignment of cultural consciousness, increased communication, and political music can leave permanent marks on the fabric of culture.

The roots of reggae in Brazil are contested but there are a number of events where reggae was introduced to Brazil during the 1970s that should be noted.

Reggae’s international influence in the 60s and 70s cannot be overstated. Its appeal as a lifestyle genre spread across the globe, catching the attention of exiled Brazilian artists Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso while in London [they lived in Notting Hill, home to a strong Caribbean community]. Soon after, Caetano Veloso released Transa with the song “Nine out of Ten”, describing the reggae scene in London. Afterwards, Gilberto Gil incorporated reggae into his 1978 Montreux concert, and then, later that year, he invited Jamaican reggae superstar Jimmy Cliff to Brazil, a point which many writers agree was the moment reggae was officially introduced to the nation.

At the time, Black Brazilians had many reasons to resonate with reggae. As many Jamaican reggae lyrics described the hardships of urban Jamaican life, Black Brazilians living in crowded favelas were able to relate to the themes of inequality in the music. Because of the shift from a military government to civilian rule in the eighties, many Black Brazilians became vocal about the continued mistreatment of Black folks in Brazil under the guise of a “racial democracy”. Out of this frustration with their societies, reggae was received exceptionally well in Brazil, embraced as a pro-Black reprieve from the niceties of Brazil’s ‘cordial racism’.

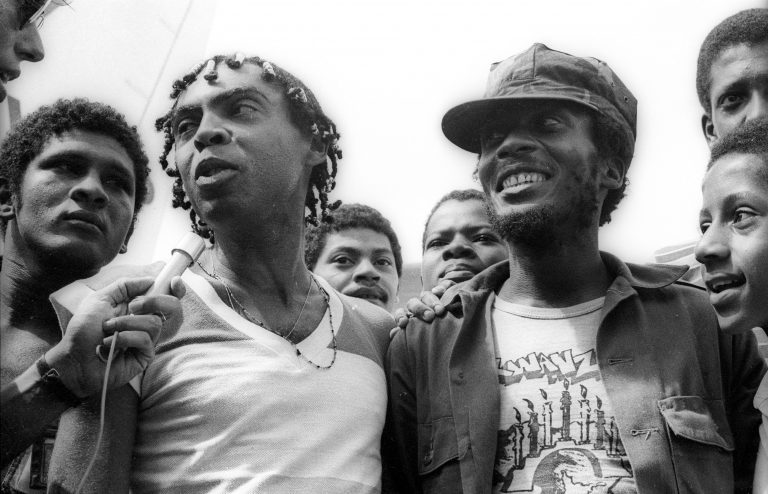

Although Brazil abolished slavery in 1888 and later developed the notion of a “racial democracy” with all equal, an idea pushed by the authorities and many intellectuals, the message of Black liberation from artists like Jimmy Cliff and Burning Spear resonated with Black Brazilians in the 80s, a time where, upon the centennial of the abolition of slavery, it felt like much hadn’t changed. Reggae gave Black Brazilians a distinctly pro-black cultural form to mobilize around.

Reggae’s increased popularity coincided with Brazil’s Black Soul movement, a sort of Negritude where Black Brazilians were unearthing a renaissance of Black art and Black consciousness through the music of James Brown and Marvin Gaye, which sought to define an alternate historical narrative outside of Brazil’s culture of casual racism. In this, Black Brazilians made mythical connections to other Black nations like Jamaica and supported other struggles through their music.

One defining example of this cross between politics and music is the emergence of sambareggae through the group Olodum, a bloco afro or Black and working class community organization. Blocos afros use music to mobilize Brazil’s Black community around social and political issues. Blocos afros also brought with them their own take on traditional carnival rhythms. Neguinho do Samba, a founding member of Olodum, incorporated Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Brazilian drumming patterns, making aesthetic links across the African diaspora and distinguishing their bloco afro from others at the time. Sambareggae successfully blended the complicated and upbeat rhythm of samba with the slower beat of reggae to produce a unique percussive sound at a tempo that everyone, not only highly trained passistas, could dance to. Olodum used their distinct platform to bring attention to racial and social inequality in Brazil, and also to align themselves with causes worldwide, including the anti apartheid movement in South Africa. For example, their 1987 carnival hit was “Faraó Divindade do Egito” (written by Luciano Gomes dos Santos), which called for Black Bahians to call on the aesthetics of ancient Egypt to empower themselves in Pelourinho, Olodum’s neighbourhood in Salvador.

Reggae’s popularity in Brazil was coupled by the fact that Jimmy Cliff, an iconic reggae artist, lived in Brazil for several years starting in 1978 and made a second home there. Even before Cliff came to live in Brazil he recorded Jimmy Cliff in Brazil (1968), a reggae pop fusion album with English covers of MPB and Bossa Nova classics. “The Lonely Walker (Andança)”, an English language version of Beth Carvalho’s classic, was a clear example of the reciprocity of cultural influence between Jamaica and Brazil.

The 90s and early 2000s were when, arguably, what we know now as commercial Brazilian reggae came to be. Bands like Natiruts, Cidade Negra, and Ponto do Equilibrio enjoyed massive success, most likely because their audience had been exposed, for at least a decade, to reggae music globally. Artists that used reggae in their work like Gilberto Gil and Olodum kept it at the forefront of the country’s consciousness, while Jamaican reggae artists like Burning Spear still enjoyed international acclaim. These bands literalized imagery from Jamaica and inserted their own struggles in their lyrics to make their music relatable to Black Brazilians and resonant with the world community. Gilberto Gil released the iconic Kaya N’Gan Daya in 2002, a cover album of Bob Marley’s classics with many Portuguese/English lyric fusions [and which was recorded in Jamaica with Marley’s backing singers the I-Threes on harmonies]. These were not Gil’s first covers of Marley’s though, he had recorded “Não Chore Mais”, a Portuguese cover of “No Woman No Cry”, back in 1979, and it remains a popular staple of his.

While in Jamaica, dancehall has replaced reggae as popular mainstream music today, Brazilian reggae and sambareggae has folded into the colorful fabric of Brazilian culture. Bands like Natiruts and Maneva dominate stadiums and pop music charts, sound systems such as Digitaldubs represent the roots of dub and dancehall, alternative musicians like Céu and Curumin deftly incorporate Jamaican influences into their cosmopolitan sounds, and a city such as São Luís Do Maranhão has become the “unofficial capital of Brazilian reggae” [read about that story here], while Rastafarian imagery and reggae paraphernalia has become commonplace alongside caipirinhas and samba music. Now, the reggae performances I watched in that sweaty São Paulo karaoke bar don’t seem so out of place; more like a most welcome cultural exchange, and medium for social change in Brazil.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.