‘Babenco: Tell Me When I Die’: A Touching Love Letter to a Cinematic Giant

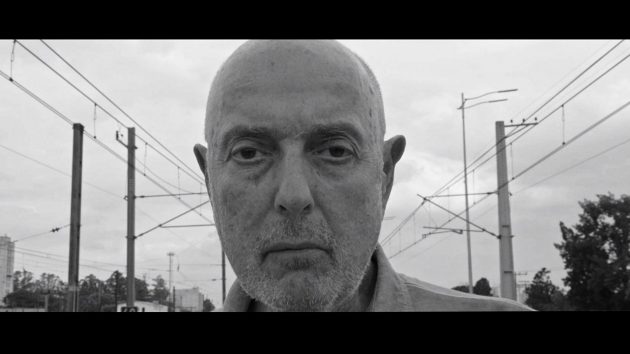

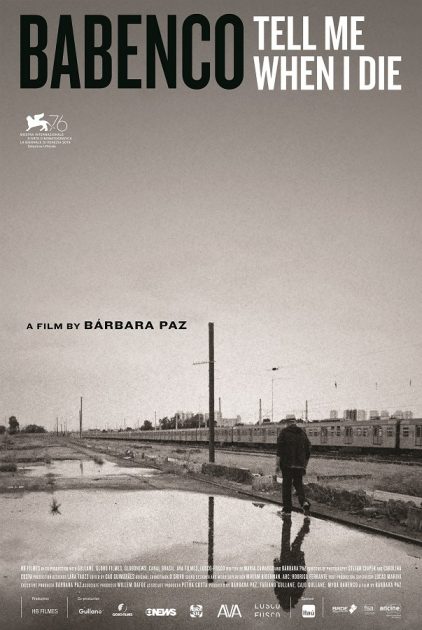

25 February, 2021Héctor Babenco, a renowned Brazilian-Argentinean filmmaker, passed away in 2016 at the age of sixty, after struggling with cancer for three decades. The fragmentary, impressionistic documentary, Babenco: Tell Me When I Die (2019) is directed by his widow, Bárbara Paz, and filmed just before his death. It was Brazil’s official submission for Best International Feature Film at the 2021 Academy Awards, which is certainly at least symbolically apt considering two of Babenco’s own films were Brazilian Oscar submissions in their time: Pixote (1980) and Carandiru (2003).

Babenco is a peripheral figure: he is and isn’t Brazilian, he is and isn’t Argentinean, he is and isn’t dead. The liminal and fragmentary nature of the narrative, and of the man, is heightened by the binaries evoked in the documentary. It is filmed in black and white. The main ‘characters’ are a couple, a man and a woman. The film draws upon the age-old binary of life and death, all the while cleaving space for complexity, for life in death.

At the start of the film, Babenco asks, “Como nasce um filme?” [“How is a film born?”]. He goes on to say it can be born from a death sentence given by a doctor, contextualising and giving life to the very film we are watching. The conjunction of life and death push at the limits of life. It evokes the beginning in the end, breaking down temporal assumptions.

In the film Babenco speaks in the voice of others or, more appropriately, in the voice of his characters. Throughout the documentary, extracts from Babenco’s own films serve to flesh out moments he himself cannot directly vocalise, taking the phrase ‘a life in art’ to an almost literal level. We are stuck in a house of mirrors; life and art are in constant imitation of each other.

He desperately attempts to have agency in the production of the film, grasping at his identity as a filmmaker. Paz, who is also an actress, is shown dancing for Babenco’s last work, a semi-autobiographical film titled My Hindu Friend (2015). We see her reflecting on her performance with Babenco right after the scene was shot, asking him if she looked like a clown. By constantly framing its subject as director and its director as subject, the film forces viewers to question who is in charge of Babenco’s depiction in the documentary. We see Babenco directing Paz, teaching her how to frame a shot, joking about the length of the documentary, telling her she needs to learn how to synthesise. The film is as much about death as it is about the process of creation: how a film is born, who owns it and whether or not it can be controlled.

Judaism is very important to the film and, consequentially, Babenco. He says, “Ser Judeu é ser nada” [“To be a Jew is to be nothing”]. He goes on to say it means you don’t belong anywhere; it means you are from nowhere. Feeling like an outsider brought Babenco to cinema. He describes it as a dark place where he sought protection, distraction. It is the nexus of his creation. Babenco tells us this propelled him to make movies about the most marginalised members of society: the homeless, sex workers, prisoners, and addicts.

The film is Brazilian, in so far as its director, and to a certain extent its subject, is Brazilian. However, it isn’t strictly in Portuguese. We also hear Spanish, French, and English. Babenco describes how difficult it was to grow up with parents speaking a language you don’t hear on the street, “like Yiddish”, he says. The linguistic ambiguity underpins the narrative. As a viewer it is unlikesly we will completely understand all the dialects spoken; like Babenco, we are almost always an outsider.

There’s a certain poignancy in the scene reproduced from Pixote (1981), a film Babenco directed in the 1980s about a homeless adolescent boy who tries to survive in a cruel world. The scene reproduced in the documentary is one of the last in the movie: it shows Pixote sucking on the breast of Sueli, a prostitute he works for as a pimp. Sueli rejects Pixote, pushing him away and telling him she isn’t his mother. This scene is rendered far more significant once you realise the actor who played Pixote, Fernando Ramos da Silva (whose life was similar to Pixote’s in some respects), was murdered in an alleged shootout with the police in 1987, six years after the movie premiered, meaning Babenco’s isn’t the only death imbedded in the film.

Babenco: “This film is based on facts that actually happened to me.”

Paz: “I don’t like that, Hector, it’s rubbish. No, it’s not that they are [based on] fact. They really happened … I don’t like [the term] inspired … It’s not based on …”

Babenco: “But then it seems like a biography.”

Paz: “Fuck it!”

The documentary isn’t a biography; it’s a portrait. It deals with what Paz considers to be Babenco’s essence without telling us the story of his life linearly or didactically. It says just as much about Babenco as it does about Paz, and their relationship. It’s a love letter to him, to film, to life, to death.

At the end of the documentary Babenco says: “I have already lived my death. All that’s left is to make the film, right? All that’s left is to make the film about my death.” The last couple of scenes are filmed in Hong Kong, but Babenco doesn’t die in Hong Kong. He dies in São Paulo, the city he considers to be his home. Ironically, Babenco: Tell Me When I Die is eponymously about a death that is never really shown on the screen.

Check out Taskovski Films for details of future screenings of Babenco: Tell Me When I Die.

Click here to read an overview of the Latin American contenders for the 2021 Academy Awards (Babenco was Brazil’s submission).

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.