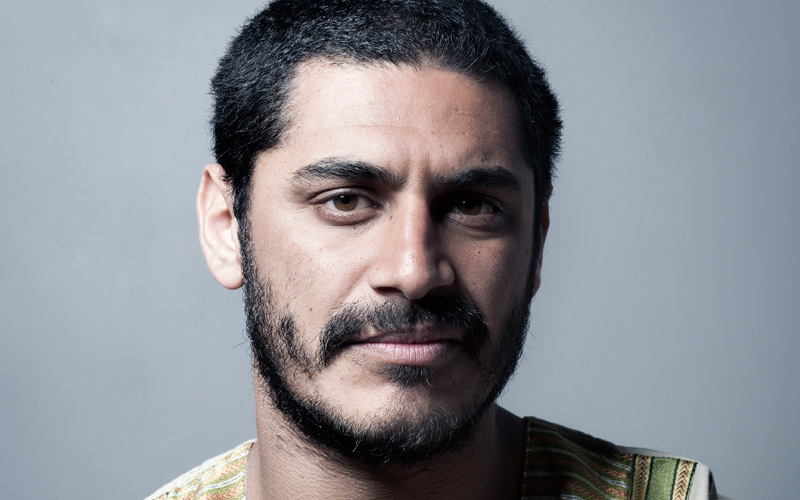

Don’t Let Go Of Hope: An Interview with Criolo (Part Two)

09 March, 2015A few weeks ago we posted the first part of our interview with Criolo, a Brazilian rapper and singer whose music transcends boundaries, classes and language barriers. After releasing his second album Nó Na Orelha in 2011 Criolo became a huge star in Brazil, winning countless awards, sharing the stage with Brazilian music royalty (Caetano Veloso, Gal Costa, Ney Matogrosso, to name a few) and touring all over Brazil, with a smattering of international dates.

I met with Criolo following the release of his third album, Convoque Seu Buda, in late 2014. It’s an album full of hip-hop, samba, reggae, afro-Brazil and funk which may well propel Criolo on to international success. It’s certainly success that would be well deserved. In the first part of our interview with Criolo we discussed his success and Convoque Seu Buda. In this second part we wanted to get a little deeper, finding out about Criolo’s roots and what fires him, as well as his perspective on what’s currently happening in Brazil.

Interview translated by Rachel Hayter and Russell Slater

I read online that you started to sing in 1989, but your first album didn’t come out until 2006. What did you do in all those years between? Where did you sing?

I sung in lots of places, but I didn’t have the means to record a CD. I sang in schools, churches, college dances, on the street… I had no money. We live in a planet that, without money, you are nothing.

But did you sing with aspiration of releasing a record, of becoming known?

I sang with fever, of course. Singing is something that… The desire to sing, regardless of whether somebody has a good voice, is something that comes from your soul. You don’t sing because you want to be recognised, or you want an audience, or you want to record an album. You record an album because you sing. It is important not to reverse the order of things. I could have not recorded a single album in my entire life and I’d still be singing every day. Because singing comes from within, from the heart, it doesn’t matter if you don’t have an audience – you just want to express yourself and tell a story.

When did you begin to rap?

In 1987 I saw a friend from school perform a verse of four lines, and everything rhymed. I’d never seen this before, I was 11 years old and I thought it was magic from another world – how did he do that? I want to do that too! So I started. And once I heard a song on the radio which was entirely in verses, and the presenter said that it was called rap, I started to rap. I really identified with the lyrics of rap because it spoke about things from the neighbourhood, everyday things, and it really seemed like they were talking about my neighbourhood, my street. The reality described was very close to mine, so in 1987 I started to write. After 2 years, I had the opportunity to sing. So I started writing aged 11 and I first got on stage at 13.

How did your family help shape you as an artist. I read that your mother was a big influence. Did she influence your work?

Yes, but later in life, not when I was a child. When I was 11, 13, 15 I constructed the universe in my way. My mother had her own world view, but her role as ‘mother’ was still very present. When we grew up, there was more space for her to share her ideas with me and my siblings, so that we could understand the way she saw the universe… She naturally values art, which is something that has always been present in my family, it’s fundamental. Later my mother started reflecting upon text and thoughts, more specifically within the world of literature. Valuing and thinking about art was always present in my mother’s world view.

Why did you start Rinha dos MCs [this was a sarau, a meeting place for rappers, poets and artists that Criolo set-up before releasing any records, and that provided a platform for artists like Criolo and Emicida to perform]?

In Rio de Janeiro I encountered a freestyle group, really strong, larger than life, really interesting, that was called Liga dos MCs. I spoke with a friend “why can’t São Paulo have something like this? It has to have this as well” and this was my inspiration. A group of youngsters from Rio de Janeiro they were my inspiration for making Rinha. The people had this love for freestyle rap, but more than this I saw that they could provoke so many people from their neighbourhood and get them involved in this art.

There was a freestyle battle, dancing, vinyl music – there was no computer, just vinyl – and the people had other skills too… there was a photographer, writer, painter. I wanted to make something like this as the people of the neighbourhood didn’t realise there was all these artists in their neighbourhood. Then I started my own meeting with youngsters and it began to grow and grow across the city, and later to other parts of Brazil.

Do you think there’s now a marginal voice in the mainstream with writers like Ferréz, Alessandro Buzo and Sergio Vaz becoming known, as well as yourself?

I don’t know, it could be like this. Maybe mainstream has a different meaning, because Sergio Vaz – a great writer – is known around the world and does not have the power of a corporation, he’s not a multi-national, neither is he a political party or economic entity. He is a great artist. Because mainstream, as most people think of it, always has great power at the top and a global structure that allows any artist to become known. But Ferréz is also known worldwide and he’s an artist who came without the need for a structure to think that he could be a mainstream artist, he came with the strength of his art. For us, it does not matter whether it’s seen as mainstream or not, our voice is alive and if the person opens their heart, that voice can communicate with them.

Have your experiences travelling around Brazil consolidated or changed your perception of the people of Brazil?

When you travel around Brazil more than anything you see how difficult it is to survive. For many people their reality is pain and when you come into contact with that reality you realise all the different ways there are of trying to survive with dignity, and how many people are really suffering, but still they’re trying to stand out, despite suffering so much. So one of the great learning curves after so much travel, especially so much travel outside of Brazil, is that it strengthened an idea of mine of how our people are so rich culturally, really rich culturally, and full of dignity and hope.

I saw the protests first-hand in 2013 and I saw the energy. Is this energy present in your music?

I don’t know. I don’t know if it’s the same energy. Because I think it’s beautiful to see the people going to the street, to the main street, it was something historic. My neighbourhood, Grajaú, has one million residents, and next to it is Capela do Socorro, where there are three million people, both neighbourhoods rose up and went to the streets. Can you imagine that many people going to the streets, or what could happen?

There exists an energy in the society that is important: to think about the social construct of the future, or to think of the social construct starting from now. For me this is the great thing about what happened in 2013, to make people think. Whether we understand our history or not, it’s more about talking and thinking about this social construct, that is the wonderful thing, independently of what class you have or what has been refused you.

Did things change in Grajaú with this energy?

No, despite how much suffering there is there, nothing changed. [It’s tough] to change a country as big as Brazil, which you have to think of as a continent. There is an energy that is always there in the ghettoes, in the suburbs, whether they are ghettoes in the centre or not. Always this energy is there, it has always been there. It’s not because of what happened.

What’s the solution?

Well what happened was not the solution, but a lot happened. We saw that to communicate in our generation is different than with the last generation, there are new communication paths. The more tools you have to communicate, the better chance we have of being able to do things and organise things. We found out who lived in other neighbourhoods and that strengthened us when we went to the streets.

You have to think of the technology, you have to think of everything that happened as a grand gesture, as this undoubtedly was, but you also have to think about the current politics. As interesting as the technology is if a politician wants to make it difficult for us to communicate or takes away our tools, then nothing happens.

Now, my generation throughout the whole of Brazil was extremely discontent with so many inequalities and it exploded, but there will be more explosions. It has only just begun. We are living this moment.

Is there a message in your music?

I don’t know, maybe. You should not disconnect yourself form positivity. You should not disconnect yourself from wanting something good. Want a better world. Grow with us. I hope that [the message] is something like this.

Convoque Seu Buda is released by Sterns Music and available from iTunes, Amazon UK and Amazon US

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.