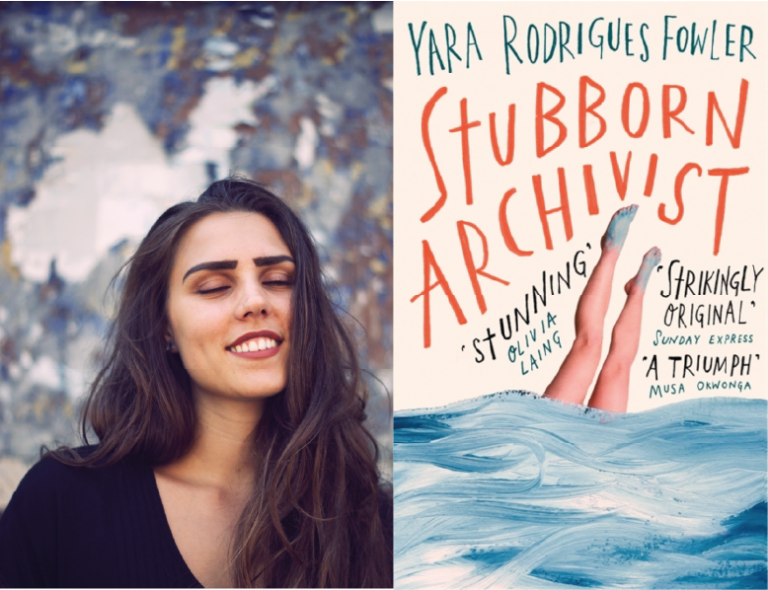

Double Lives, Healing and Alegria: Yara Rodrigues Fowler on ‘Stubborn Archivist’

24 September, 2020Yara Rodrigues Fowler grew up in a Brazilian-British household in London, where she is still based. She is the author of Stubborn Archivist, which was shortlisted for the 2019 Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award and admired by authors such as Nikesh Shukla, who described Rodrigues Fowler as “a talent to watch”. Stubborn Archivist is described by publisher Fleet as a “novel of growing up between cultures and of learning to live in a traumatised body.” The protagonist’s story is told in beautiful, multilingual prose, dialogue and prose-poetry, moving between the UK and Brazil, from childhood to adulthood, and between different family histories, through conversations with the protagonist’s mother, grandmother and aunt. Rodrigues Fowler spoke about writing Stubborn Archivist and the response to the book, as well as Caetano Veloso, Brazilian politics and translation.

The chapters of Stubborn Archivist move between countries, time frames and narrators. Did the structure move around while you were writing?

The order did move around: in fact, the US version has a different chapter at the start. But the flow or arc, which follows the protagonist’s journey as she processes her experiences of abuse, has always kept its shape. It moves from a place of trauma and pain (part 1), to self-knowledge and agency (part 2), to some joy (part 3). My question to the protagonist at the end of the novel is, rather than simply notice how fucked up the world is, and trace how that happened, “What are you going to do about it?”

The arc of the protagonist’s healing (2014 – 2015) runs contrapuntally to another timeline, beginning in 1991 when she is born. Her birth, in the year that the Berlin wall fell, marks the end of a political cold war that exists in her family, between the left- and right-wing. The novel closes on the eve of 2016, when we see, on the one hand, the protagonist’s peace with herself, her joy, and on the other, her aunt’s discovery of right-wing politics, a foreshadowing of a new era of right wing violence and polarisation.

Throughout the text, I tried to thread the history that led to both this era (1991 – 2015) and to the sexual violence that the protagonist experiences; for example, through her mother’s memories of the military dictatorship in Brazil, through her grandmother’s experience of marrying to escape poverty, and through the family story of an ancestor who raped and kidnapped an indigenous woman. I was trying to show that Brazil and Brazilian identity were built on violence against indigenous (and black) women and economic exploitation, and how this originary violence leaks even into the life of a white girl with a British passport living in south London.

One of the novel’s two epigraphs is part of the lyrics of ‘Alegria, Alegria’ by Caetano Veloso, a Brazilian musician with a connection to London, having lived in exile there during the dictatorship. What’s your relationship with Caetano Veloso’s music?

Caetano’s music has been very influential to me. I listen to his music mostly on Spotify but I think originally I came across CDs of his at home or at my mum’s friends’ houses in Brazil. He has a bilingual album ‘Transa’ which includes descriptions of London, which is very special to me.

Listening to his music, for me, is constant exercise in translation and reading (and … alegria!) – firstly, because he was often using metaphor and allusion to avoid censorship by the dictatorship; secondly, because his songs sometimes include a bit of nonsense just for the joy of it; thirdly, because I lack so much of the context for his work sometimes I’ll think I understand a song, explain my thoughts to my mum and she’ll laugh and explain that I’m missing something really obvious.

That happened with his song ‘Terra’ which it turns out was inspired by the photograph of Earth taken during the Apollo 8 mission, which Caetano saw while in prison in Rio in 1968, right before leaving for exile in London. After my mum explained, I wrote a short piece about ‘Terra’, which you can read in Five Dials online.

Part of the fun and frustration of this constant play of translation and mistranslation, is that Caetano didn’t really see the ‘real’ London when he was here either. For example, Caetano and Gilberto Gil’s song (they were in exile together) ‘London, London’ includes the lines,

A group approaches a policeman

He seems so pleased to please them

…

And it’s so good to live in peace

The period of their exile was 1969 – 7, slap bang between the Notting Hill riots and the Brixton Riots. I understand how the police in London may have seemed docile compared to police in Brazil, but the picture this song paints is a fantasy.

At FLAWA festival, you read a chapter from Stubborn Archivist that is narrated by the protagonist’s mother, remembering her activism in Brazil during the dictatorship. Why did you choose this chapter?

I always choose this chapter because I want to remind audiences as often as possible that the story I am telling exists in the world that they live in – a world where Bolsonaro is president. I want to keep reminding people of this fact; I want to make it as hard as possible for people to experience my work as in any way ‘apolitical’.

It is also a way of re-archiving, or placing into new archives (the audiences’ heads!), a piece of oral history of resistance and transgression. The graffiti in this extract reads “coragem alfredo” but it’s also an exhortation to the reader – coragem!

Stubborn Archivist covers so many themes: family, identity, depression, sexual violence, recovering from trauma, sexuality, politics. Have you been surprised at which themes have resonated with readers and reviewers?

Yes and no. I think because of the election of Bolsonaro people have been somewhat more inclined to see it as a political book – the dictatorship references I think might otherwise have gone over the heads of many English readers. Nevertheless, the Brazilian class politics, which to me are inextricable from the rise of Bolsonaro, are usually only picked up on by Brazilian readers, or occasionally non-Brazilians who have lived there. The descriptions of servant culture which defines elite Sao Paulo society, for example. I am always slightly frustrated when readers can’t read the race politics that I’ve laced in too – for example, the main family is white and the character of Marcos is described as having ‘brown hands’ but I’ve lost count of readers who racialise Marcos as white or the whole family is a kind of light brown (what they think ‘Latin American’ means).

I am very glad that most readers and reviewers understand that it is a book about sexual assault and healing. I am nevertheless always surprised by how willing some readers are to interpret the main ‘coming of age’ arc of the text as about cultural identity alone, as opposed to coming to terms with that identity through the lens of the violence she has experienced because of the identity.

Lastly, it’s a queer book. That is both obvious and quiet, some readers don’t notice this at all; to others it’s laughably clear. This is what I intended.

There were sections of the book that made me laugh, like the scene with the friend turning up at the airport for a holiday to Brazil dressed in “colonial chic”, or the protagonist’s commentary about fruits having “double lives” in English and Portuguese. Was it difficult to write humour into a story of a woman recovering from sexual assault?

It’s funny really because I just write people the way they talk, and it turns out the way people talk – or the way I hear it – is very funny. We are all constantly saying silly things, and cultural norms taken for universal truths are inherently silly. But yes, it was very important to create a text that has joy and silliness in it – because this is what I think survivors deserve and this text is for them – and to use this as a way of processing hurt and hurtful circumstances.

Can you give an example of a fruit with a “double life” in English and Portuguese?

Oh yeah.

Passion fruit / maracujá – utterly unrecognisable fruit in the UK

Pineapple / abacaxí – the juice especially is totally different here and in Brazil, where its fresh and foamy as opposed to here where its clear (like urine) and from concentrate.

These are just a few that come to mind. Just as the words changes when transported from one language to another, they change when transported across the world – this is, I suppose, what I meant by double lives. It is the fate of anything that migrates or lives in translation, I think – including, for example, people who ‘code-switch’ between different class groups in the same country.

How did you hope readers might react to the mixture of English and Portuguese in Stubborn Archivist? The protagonist talks about the two languages “bleeding like clothes in the wash”.

I hoped that Brazilian-British (and to an extent Brazilian-North American) readers would take joy in this small linguistic corner I made for us. In particular those who grew up in English-speaking countries speaking Portuguese at home. For readers who only spoke English, I wanted to create an experience of alienation: mirroring, in inverse, the experience of migrants in the UK.

I also wanted to separate the idea of two separate languages floating in parallel, and show that language can be a continuous fabric or stream with words and meanings which exist uniquely, all untranslatable, and which can all be called upon – in any combination – for their unique meaning. I believe in something postcolonial theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak said, that translation is both “necessary and impossible” (from her essay ‘Translation as Culture’).

Fruit words and place names are some of the relatively few indigneous words that are common in Brazilian Portuguese, which is part of why they are listed at the end of the book.

Stubborn Archivist touches on the exoticised way in which British people and culture look at Brazil and Brazilians. I wondered if your experience of being British-Brazilian informed some of the examples of this?

Yes, of course. In particular, because my name is clearly foreign, I find that “Where is your name from?” is often used as a polite substitute for “Where are you from?”. The hypersexualising, especially as a teenager, both here and in Brazil was also relentless. They manifested differently: in Brazil I would be praised for my white features and here exoticised for my ‘Brazilianness’. This is also the experience of the protagonist in Stuborn Archivist.

Although this happens all the time to me, a white Brazilian with a British accent (albeit with a Brazilian name), it is the result of a racist mythology set up to naturalise the rape of black and brown brazilian women primarily; specifically, the myth of the pliant indigenous woman and the hypersexual African woman who, owing to their ‘inherent’ racial characteristics, are always consenting and cannot be raped.

I know that you’re a trustee of Latin American Women’s Aid. How the organisation has been reacting to the pandemic?

For readers who aren’t familiar with LAWA, we run the only refuges for Latin American women in the UK. And I’m a trustee which is a voluntary role do to with governance; I don’t do any frontline work.

We don’t yet know the answer to this – the pandemic is ongoing and so are the economic effects of people being made redundant and having no childcare. This, and lockdown, has made it harder for women to leave abusive situations.

Until the government properly funds these essential services, organisations will always be scrambling for funding in order to exist. This is at best a distraction and for many services has shut them down. Organisations like LAWA should be permanently funded to do the work we need to do.

Stubborn Archivist is published by Fleet and is available at Hive (UK) and Bookshop (USA).

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.