Getúlio: The First Carioca I Met

06 March, 2021I was a fairly clueless adventure-seeking 21-year-old when I visited Rio for the first time in 1994. The sky was always grey. It rained often. My Lonely Planet remained on the bus after my long, achy journey from Bahia in Brazil’s distant north-east. I stayed at a budget place called the Hotel Turístico. Popular with backpackers, it was located in the Glória neighbourhood.

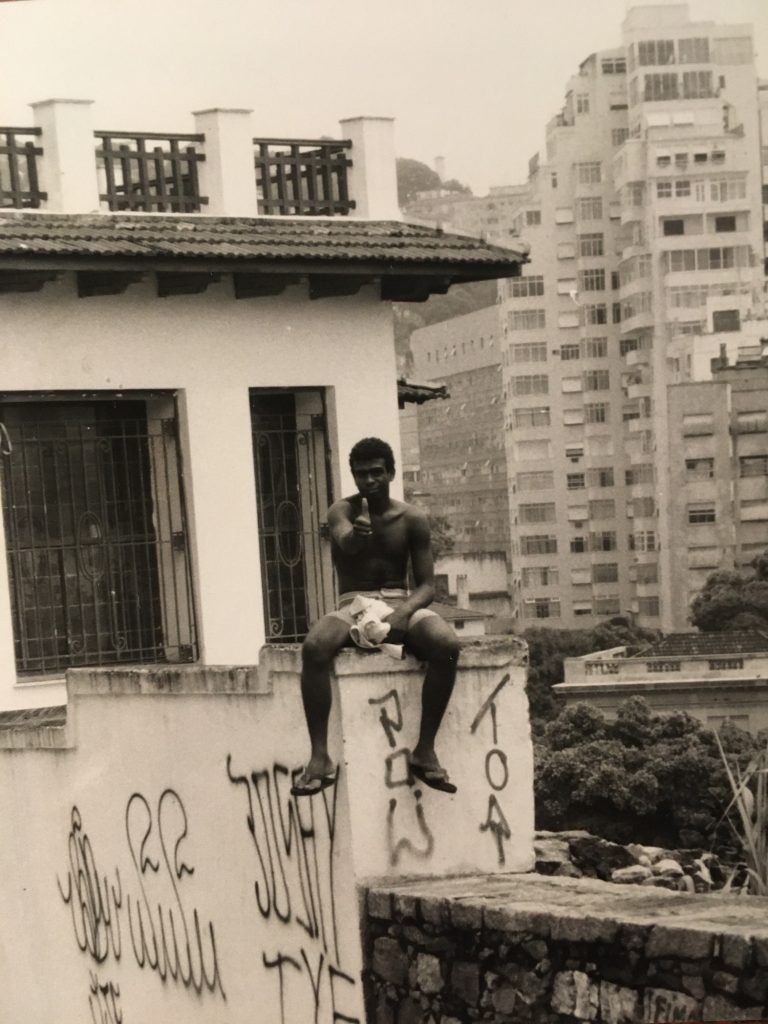

The first carioca [Rio de Janeiro resident] I met was homeless Getúlio. He stood on the pavement near the Turístico when Scotty, a Kiwi traveller I’d met at the hotel, pointed him out. Getúlio came over with lots of thumbs-up and backslapping. He spoke a few words of English and Scotty invited him for a beer. I was the only one who had any Portuguese and acted as interpreter. Scotty and his friend Mark were strong, red-faced boys on a round-the-world trip paid for with farm labour. We chatted standard man talk; football, girls, Brazil. Then Getúlio asked where I came from.

“Londres?” he replied. “Lon-dres? Como no filme Lobo Americano em Londres?”

He leant back, cupped his hands and let out a comedy howl. An American Werewolf in London, he said, was one of his favourite films. It seemed an incongruous choice for a homeless youth in Rio. Getúlio was gregarious and charismatic and I liked him. He lived alongside two friends underneath an ancient battered dumper truck parked in front of the Turístico. The hotel manager brought them breakfast every morning.

Like me, Getúlio was 21. A couple of days later, when he learnt that Rio’s police had extorted a substantial sum of money from me, Getúlio put on a funny voice poached from a daily live crime TV show to cheer me up. The presenter of the show would describe crimes in a terribly serious mock drawl. Getúlio rehashed this to describe what happened:

“Heere, in Riioo de Janeeerooo, the griiingooo, had problems with the poliiice in Coooopaacabanaaa.”

Getúlio made ends meet looking after cars parked on the street, but only when the area’s ‘owner’, a bony old man called Death – because he looked like the Grim Reaper – didn’t show up. Getúlio had second dibs on the patch, where up to ten cars could park, and that, on a good day, could pay reasonably. He was waiting for Death to retire in order to take over his business. In the meantime, he did what he could. I looked, listened and learned. Getúlio had a love–hate affair with his city. He knew a lot of people in the neighbourhood and always stopped to talk to them. He frequently said you could do whatever you want in Rio. But he also looked disenchanted; Rio was a violent place, he used to say – an observation I kept hearing.

His friends had their own ways of making money. Drug buyers used them as runners to go to a nearby favela to fetch drugs. They pulled up in cars, gave money to the kids (I call them kids but we were all roughly the same age, late teens, early twenties) who crossed the road to a moto-taxi service. The runner would get a bike to the favela, do the deal, come back down, hand over the drugs and get paid. Getúlio called cocaine use ‘Colombian Karate’. He and his friends were resourceful and dynamic. Hanging out with them was a fascinating way to pass the hours.

I was also low in funds, following my run-in with the police. A cousin was wiring me some money but the process was slow. Consequently, one day I went without food. That night, when Getúlio discovered that I hadn’t eaten, he put his arm over my shoulder and jovially frogmarched me across the street.

“What do you want?” he asked.

We were in a ubiquitous-looking bar with a rectangular steel counter. Bottles of booze were piled high next to fridges. An old TV set broadcast the news. Workmen who looked like cleaners were tucking into big plates and I pointed to one. Getúlio ordered us a coke each. He wasn’t hungry. Across the bar, I spotted two men I recognised from the Turístico. A German and a man I hadn’t spoken to, but whom I knew was English. The German nodded in my direction. The weather was still bad and they were killing time drinking beer. I squeezed a slice of lime into my coke and sipped, savouring its sugary cold freshness against the ice. A plate of meat arrived with sides of rice, beans and salad. The food was hot and I was hungry.

“Eat,” said Getúlio.

I hadn’t realised how hungry I was. As the beans and rice filled my stomach I felt pleasure and a little tiredness. Next to me Getúlio spoke to a tall, athletic looking man. He introduced him as a former professional football player celebrating the birth of his twins.

“Congratulations!”

I raised my coke to his glass of beer. Clink. His eyes were drunk and dangerous. He was drowning his sorrows, not celebrating. Behind him, a rat the size of a small cat scuttled along a stretch of wall into a ventilation shaft. Getúlio continued talking as I finished my food. Their conversation grew in volume. Getúlio was uneasy. He looked annoyed with the footballer. Ending the conversation, he put a hand over my glass.

“Don’t drink any more,” he said.

I was still thirsty but not about to overrule Getúlio. He knew what was what. He paid and we left the bar without saying goodbye to the new father, whose back was turned.

“That was bad,” Getúlio said, when we were back over the road.

“The guy wanted to rob you, to put something in your drink. I said you didn’t have any money but he wouldn’t listen. I told him you were my friend and he said a Brazilian should never make friends with a gringo.”

The next day in the hotel foyer I waited for my cousin to call about the money. If it came through, I was going to be OK. It wasn’t much but meant I could pay the hotel, spend a few more days in Rio and leave. I was thinking about what I could do during this time, when I noticed the Englishman from the bar hovering. He wanted to say something.

“Hi.”

“Hello.”

“I was wondering.” He paused. “Well, we were wondering…”

“Yes?”

“We saw you eating in the bar yesterday.”

“Yes, I was. Rice and beans!” I smiled.

“Well… we were surprised to say the least.”

He paused and fixed his eyes on mine.

“We were surprised,” he continued, “that you didn’t share your meal with your friend.”

How was I going to explain this?

“Well he’d already eaten. You see, actually, he paid for my meal. It sounds strange, but he bought me lunch.”

I admitted to myself that this looked very odd. What must he think?

His eyes narrowed. “How could you? You know these people have nothing!”

My fuse went before he could continue. Maybe he wasn’t able to finish his sentence anyway. Maybe the concept was too much for him. This spoilt young Englishman before him, his co-national, with the audacity to take money off street kids, not just take their money, but to convince them to buy a meal? What sort of perversion was this? What sort of character could I be? All this was going through my mind, and maybe his, when I stood up, mumbled something about did he really think that I would take money from them with nothing in return and walked out onto the street where I found Getúlio. He stood happily next to a pair of running shoes. They were drying off yesterday’s rain in an air vent and their laces blew in the wind. I leant against the wall next to him and looked out at his street corner comfort zone. Part of me felt guilty for allowing him to buy me a meal. On the other hand, he had offered and I had avoided going to bed hungry. My values, my ideas of right and wrong, were being scrambled. I was in an unpredictable situation.

After a few days off sick, Death came back to work, plying his trade in the drizzle. Peering out from underneath a transparent plastic raincoat, with his bony outline and hooded face, he really did look like the Grim Reaper. In the evening we sat in a storefront, backs leaning against the metal shutters, to eat meat kebabs barbecued by an old lady over an improvised tin charcoal burner on the pavement. Getúlio called the lady – who let us consume on tick, we would pay for it later – tia, meaning Auntie. This didn’t mean that she was actually his aunt; it’s a term of affection that young Brazilians often use for older women. She served the sticks with manioc flour and tomato and onion chutney. We washed them down with beer, which she kept cold in a polystyrene container. We ate a few each and were dividing a final beer when the German from the hotel walked past. He saw me, stopped and turned.

“What are you doing here?” he asked, incredulous and condemnatory at the same time.

“Drinking a beer!” I held up the can to show him.

Before I left the city I split my resources with Getúlio and we embarked on small adventures. We tried to take the old rickety tram that went from the centre of town over the white arches of Lapa to Santa Teresa. This would replace the Sugarloaf Mountain cable car ride that I couldn’t afford. The quaint tram harked back to the era when Rio’s bourgeoisie still occupied the hillside mansions of Santa Teresa, looking over the city centre, before they fled for the high rises on the beaches. Santa Teresa became dangerous throughout the 70s and 80s, and artists, leftists and favela dwellers now occupied the neighbourhood. The fugitive and ‘great train robber’ Ronnie Biggs lived there. I had heard that visitors paid cash to attend barbecues thrown by Biggs where his mates, like fellow English villain ‘Pretty Boy’ Dave Courtney, would drink to excess and smash beer bottles on their own heads. I fancied trying to see his house.

We bought tickets for the tram and during the long wait Getúlio went to pee. The tram was ready to leave when he came back but something had happened.

“Let’s go, quick.”

Had he argued with someone? We’d waited ages for the tram and had paid for tickets. What could it be? Getúlio walked fast and only stopped a long way from the tram station.

“There was a dead body in the toilet.”

The night before I left Rio we visited the famous Copacabana neighbourhood on foot. On the way there, Getúlio climbed a grass verge at the edge of a tunnel. The incessant rain had turned the grassy slope into a natural luge that he slid down on his back, whooping. The muddy slide was much too fun to miss and I followed suit. We emerged into Copacabana covered in muck. Too poor and filthy to step across any threshold except that of the worst drinking hole, we spent our remaining cash on booze.

On my last day, a public holiday, a football derby was on in the city. I was sitting outside the hotel, when, with a snap and shout, two boys jumped off the back of a bus, a woman’s handbag in their hands. Colombian karate business was brisk and Getúlio’s mates were frequently up and down the hill. I asked whether he could take me to the favela. The parallel world up on the hill intrigued me. He wouldn’t do it though; it was too dangerous, he said.

I needed to make a last international call. The streets were empty and Getúlio walked with me to make the call at a telephone exchange in the centre of town. Every time we passed a destitute person he commented that such sights never appeared on postcards of Rio. At the exchange, we waited while a dramatic Italian begged for money from someone at the other end of the line. His loud voice filled the place with desperation. Never one to miss a joke, Getúlio nudged me and nodded towards the Italian.

“Al Capone,” he whispered, with a wink.

We said goodbye at the bus station. I gave him a few notes. They added up to little but even so, he used them to pay for access to see me off on the platform.

Decades later, reading up on the Afro–Brazilian religion Candomblé, I learnt that one of the faith’s most important deities – known as orixás – is Exu. Exu (pronounced eshu) is the orixá of change and transformation, who, according to legend, sits at a crossroads. Childish, mischievous and filled with creative grace, Exu has the power to make things happen. Candomblé believers often call homeless people ‘children of Exu’ and say that through contact with this orixá, one can attain the path to righteous living. I never saw Getúlio again. But I spent most of the next twenty-five years of my life working for disadvantaged Brazilians.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.