South America via Berlin: Three Resurrected Rarities

28 May, 2023Berlin’s independent Altercat Records label is rapidly becoming one of the most interesting players in the crate-digging universe. During the merry month of May, the label reissued a trio of obscure rarities from the 1970s: two from Brazilian artists temporarily domiciled at the time in France and one from Argentina. While the three will have a distinctly minority appeal, the label’s customary high-quality production values (the sound mastering is masterful and the accompanying booklets serve as required bedtime reading) will make all three a must for collectors and lovers of South America’s rich musical heritage.

Naná Vasconcelos: Africadeus

***

Long before Juvenal de Holanda “Naná” Vasconcelos from Recife in north-eastern Brazil was the go-to name for anyone wanting to add some “exotic” percussion to their album, before he had won seven consecutive Down Beat polls as “Best Percussionist of the Year”, before he had won the first of eight Grammies, and just after he had left Gato Barbieri’s touring band, Naná found himself in France. Producer, composer and lover of Brazilian music, Pierre Barouh, offered him the opportunity to record an LP for the Saravah label he founded in 1965.

The resulting album, Africadeus, came out in 1973 and built on the kind of long solo improvisations Naná had already recorded, two years earlier in Argentina, as part of a record with guitarist Agustin Pereyra Lucena (also resurrected by Altercat Records, back in 2020). The first side is dedicated to the title track, during which Naná puts his trademark berimbau through its paces for almost 20 minutes. On Side B, he adds his distinctive voice, hand drums, shakers and other effects to the mix. On the shortest track, he sings the “Abôios” – the songs of cowherds – which sound to my western ears like a heated committee meeting of tribal elders in some clearing of the rainforest. On the second, 12-minute “Seleçao de Folclore”, Naná – as he writes on the album’s cover – takes the selected “folklore of several regions of Brazil and [interprets] it with the ‘berimbau’.”

It adds up to a remarkable document of the percussionist’s native Afro-Brazilian musical culture. Perhaps just as remarkable is the fact that this record remains in 2023, seven years after Naná’s death secured him a place among the immortals in the pantheon of Brazilian music, the kind of acquired taste reserved for aficionados. What an incredibly bold artistic decision it was on Pierre Barouh’s part to release this on his label half a century ago. Top marks to Altercat’s founder, Sergi Roig, for following in Monsieur Barouh’s footsteps.

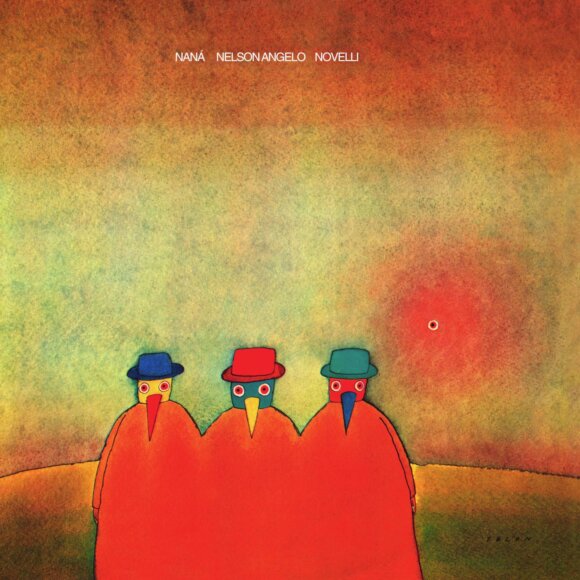

Naná Vasconcelos, Nelson Angelo & Novelli: Naná-Nelson Angelo-Novelli

****

Two years later, this album appeared on the same label. It was Naná’s suggestion to Pierre Barouh that he should record an LP with fellow Brazilians, guitarist Nelson Angelo and bassist Novelli. Naná and Novelli, both natives from Recife, had known each other for a decade and both knew Nelson Angelo from the group A Tribo that included Joyce Moreno, with whom the guitarist recorded an album appropriately enough for the Berlin-based Odeon label, Nelson Angelo e Joyce. She and Naná would go on the following year to record, again in Paris, the exquisite Visions of Dawn with Mauricio Maestro, rescued from obscurity in 2009 by Far Out Recordings. Described by Joyce Moreno herself as “a work of three heads”, it is in some respects the closest parallel to this re-release by three musicians who adopted the motto of the Three Musketeers during its recording, “One for all and all for one.” Nelson Angelo would describe a friendship that was “very great, and we shared a very big dream that led to this work.”

Directed by Barouh and the celebrated Michel Legrand, it’s unsurprisingly a more accessible affair than Africadeus. Three heads can be better than one. The eight tracks are made up of five compositions by Nelson Angelo, two by Novelli and one by Naná. The longest is the closer, “Pinote”. “It’s Naná with percussion stuff and voices,” the guitarist explains, “with overdubs, because at the time we didn’t have conditions to put twenty people playing in the studio. So Naná did vocals, overdubs, this and that, everything.” Elsewhere, the percussionist is heard largely on what appear to be tablas, as on Nelson Angelo’s “Aranda” or “Tiro Crusado”, for example. On the latter, perhaps my personal stand-out, his hand-drumming pushes along a lively mix of acoustic guitar, double bass, vocals and overdubbed organ. The preceding instrumental, “Garimpo”, also composed by the guitarist, apparently had lyrics that were not recorded. Novelli’s “Toshiro” probably comes closest to the ethereal spirit of Visions of Dawn, while his jazzier “Baião do Acordar” would go on to be re-recorded by the likes of Airto Moreira, Egberto Gismonti and Wagner Tiso.

With its striking, mysterious cover by the Belgian artist, Jean Michel Folon, (dubbed “three beaked men do not kiss” by the three musicians) this is a really desirable album. If it doesn’t quite scale the rarefied heights of Naná’s tripartite delight with Joyce and Mauricio, it comes close. I should leave it to Nelson Angelo to suggest “why this record is eternal. There will be nothing left standing, but as long as there is something left, this record will be there. It is unique, excuse my pretension.”

Horacio “Chivo” Borraro: Blues Para un Cosmonauta

***

Meanwhile, back in Argentina… Recorded in the same year as Africadeus, but not released until the same year as Naná’s Saravah follow-up, an Argentinean tenor saxophonist, composer, painter, writer and… architect was busy creating something weird but rather wonderful. It’s weird because roughly half of the album featured a young Brazilian musician who, as Horacio “Chivo” Borraro laughs, “didn’t play jazz, in fact he had no idea about jazz.” But he met Stenio Mendes at a concert, liked the sound of his music and particularly his craviola – a very singular, guitar-like cross between a cravo (or harpsichord) and a viola caipira (a Brazilian ten-string guitar) – and invited him to come and record two of his songs on his jazz album. As Mendes recalls, “He was determined to incorporate the timbre of the craviola into the language of jazz… Borraro was like a wizard for me, he was the one who introduced me to the infinite breadth of jazz and its musical universe.”

So Mendes went along and played his songs, and Borraro and his group – a splendid rhythm section of Nestor Astarita on drums, Jorge “Negro” González on double bass and Miguel “Chino” Rossi on percussion and effects, along with the producer, Fernando Gelbard, on piano and keyboards – added “a bit of jazz”. You just don’t do that kind of thing! But Borraro could and did. And so Mendes’ two long numbers, “Líneas Torcidas” and “La Invasión de Los Monjes”, open sides 1 and 2 respectively. Both are built around the unusual timbre of the craviola, with sax and keyboards grafted on but all held together by a seamless rhythm track. It shouldn’t work, but it does… kind of. If you didn’t know the story, you’d probably accept it as a quirk of the instrumentation. But knowing it, the two tracks appear to stand in fairly stark relief beside what follows: the title track, with Borraro on piano and Gelbard on other-worldly keyboards, skirts the interstellar territory of Sun Ra (interestingly, his close friend, the celebrated clarinettist Buddy DeFranco, requested the score for the track but seemingly didn’t know what to do with it); the stand-out “Canción de Cuna Para un Bebé del Año 2000” continues the intergalactic theme, but this time constructed around an achingly beautiful melody played first on tenor sax and then on Mini-Moog; and the final “Mi Amigo el Tarzán”, with its funky bass line, impassioned sax and fuzzed-out keyboards leads fittingly to a brief but wild climax to the album.

Ultimately, then, you could conclude that Borraro’s laissez-faire approach to making this led to an artistic failure. Perhaps. But then, on the other hand, there’s something endlessly compelling about a noble artistic failure. Think, for example, about the world of cinema and films like Marlon Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks or Michael Cimino’s Gates Of Heaven or even arguably Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. Not that Blues Para un Cosmonauta would sit on quite that kind of level, but what a strange and fascinating tale this album tells. Personally speaking, it’s one of the most curious yet endearing jazz records I’ve ever heard. “Chivo” Borraro died at age 90 in May 2012, but heartiest thanks to Altercat Records for bringing his extraordinary album back to life.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.