Tropicália The Film: An Interview with Marcelo Machado

05 July, 2013Between July 1967 and October 1969 a group of Brazilian musicians created a musical movement known as tropicália. Inspired by Brazilian music, art, literature, theatre and cinema as well as The Beatles and Rolling Stones, they created a style of music that was seen as being so revolutionary that it’s two lead protagonists were forced to leave the country. Tropicália is the first documentary to focus on this period in Brazilian music, a period of just two years that continues to reverberate with new audiences around the world.

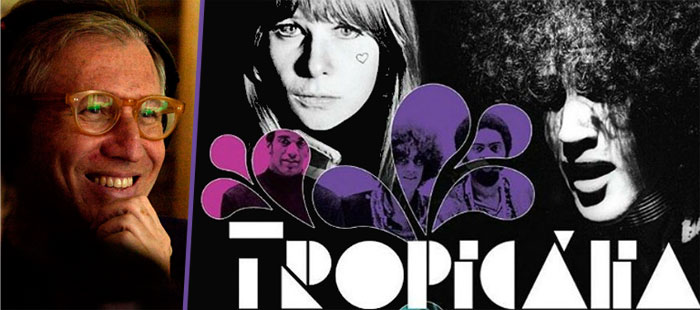

Tropicália, the film, is directed by Marcelo Machado (pictured above left), a Brazilian documentary maker and frequent collaborator with Fernando Meirelles (who executive produced Tropicália). I met Machado to discuss why now was the time to make a movie about tropicália, what made the movement so special and why people just can’t seem to forget these two years of Brazilian history.

Machado first encountered tropicália when just a child: “This was the first music that I gave attention to. When I was 10 years old they had this festival on TV [The TV Record Pop Music Festival in July 1967] so I watched Caetano Veloso sing “Alegria, Alegria”, Os Mutantes with Gilberto Gil [singing] “Domingo No Parque”. The first thing that I understand now is that I couldn’t understand the lyrics. At the same time I was listening to The Beatles and Rolling Stones and I couldn’t understand [them] either because it was in English.”

That festival appearance was the first time mainstream Brazil encountered tropicália. Caetano Veloso’s song was full of pop culture references and had a structure like no other songs at the time. He was also backed by the Argentine garage rock band The Beat Boys. Gil was no less controversial. His song had elements of candomblé, including the use of the berimbau (an afro-Brazilian instrument) but he also had a string section and Os Mutantes as his group. For many the sight of a rock ‘n’ roll band playing along with a Brazilian pop group with an orchestral arrangement was an epiphany (you could equate it to Bob Dylan playing at the Newport Folk Festival) and the whole tropicália movement took on a counter-cultural significance, a beacon of hope against the military dictatorship of the time, though this wasn’t in the traditional sense.

Machado explains: “They were from the left these kids, but the traditional left didn’t agree with their ideas, and the right neither. They were a counter-cultural movement, against the situation, but not in the way the traditional left was doing. They were not pretending to be leaders of a Brazilian revolution, they were doing music and discussing Brazilian contradictions in this hard political environment, the beginning of the military dictatorship.”

I had met Paula Cosenza, the producer of the film, at an earlier date, and she had told me about some of the interesting footage they found which adds to Machado’s comments: “We have archival material from a speech Caetano Veloso gave in 1968 in Brazil and he was being booed by the left-wing audience. For the left they expected you to talk about politics because we were under a dictatorship. They expected protest songs from Caetano Veloso and Gil. They really were not conformist, they didn’t want to be left or right.”

When I spoke to Machado he was at pains to point out that tropicália is the name for a completely Brazilian way of thinking, that’s not confined to just those two years of music, as Machado explains: “The idea of tropicália wasn’t born at this time. The idea of anthropophagy, of Oswald de Andrade, came in the 40s and spent 30 years in the shade until it came again.”

The musical movement attached to tropicália should then be called tropicalism. It was this music that caught the ear of Beck, Kurt Cobain, Devendra Banhart and Gruff Rhys who all fell under the spell of Gil, Veloso and Os Mutantes. Educating this new audience that tropicália is more than just music is clearly one of the main reasons Machado wanted to make this film, as he told me: “The people around the world who are listening to this music don’t know that it’s more than just music during this period of time. The exile of Caetano and Gil [who were imprisoned and then told to leave Brazil, doing so in October 1969 with a farewell concert] and how Os Mutantes came from an Anglo-American music, how they mixed with Tom Zé, but also how they were related to Glauber Rocha in cinema, and some of the plays of José Celso Martinez Corrêa, some of the art of Helio Oiticica, and what they were thinking about, the idea of anthropophagy, you need to eat your opponent and take the best; that is the story [I want] to tell.”

This idea of anthropophagy, of cultural cannibalism, informed the way Machado chose to direct the film. “The visual language has a lot to do with cultural anthropophagy, using another people’s material and interfering with it. The movie is a panel using material from 1967, 1968 and 1969. I took pieces from movies of all the important Brazilian directors, like Glauber Rocha, Leon Hirshman, Arnaldo Jabor, Carlos Diegues, Walter Lima Jr, Rogério Sganzerla, José Agripino de Paula and many others. [This film] it was a good opportunity to link the audience with other aspects of our culture.”

One of the interesting aspects of the Tropicália film is that it continues to London following the exile of Gil and Veloso, with a lot of exclusive footage of the Brazilians in the UK. Although it might seem that living in London in 1969 would have been a dream for many musicians, the experience of the two Brazilians was very different, as Machado explains: “[During] the London exile Gilberto Gil was more excited and used to go out to watch concerts all the time. One of the his idols was Jimi Hendrix [who was playing in London at this time]. Caetano always talked about the Rolling Stones but I am not sure he listened to them live. He was so sad being apart of Brazil that he stayed at home most of the time.” This indifference from Veloso comes across in the film where he shows little interest in being part of the hippie movement while at the Isle Of Wight festival.

44 years after tropicália ended with the exile of Gil and Veloso, and hence the break-up of the collective which defined the music, why does tropicália continue to be so influential? Machado wraps up our interview:

“The legacy of tropicalism is their music, the example they gave to new generations about creativity, about being open and interested in what is new, about not being afraid of the others and ready to ‘eat the foreigners and use their energy’ to build a better way of life. Art inhales us for life and after more then 40 years the tropicalists still do this. They are a source of inspiration for all of us.”

Tropicália is currently being shown in UK cinemas. See http://www.tropicaliafilm.com/ for all the screenings.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.