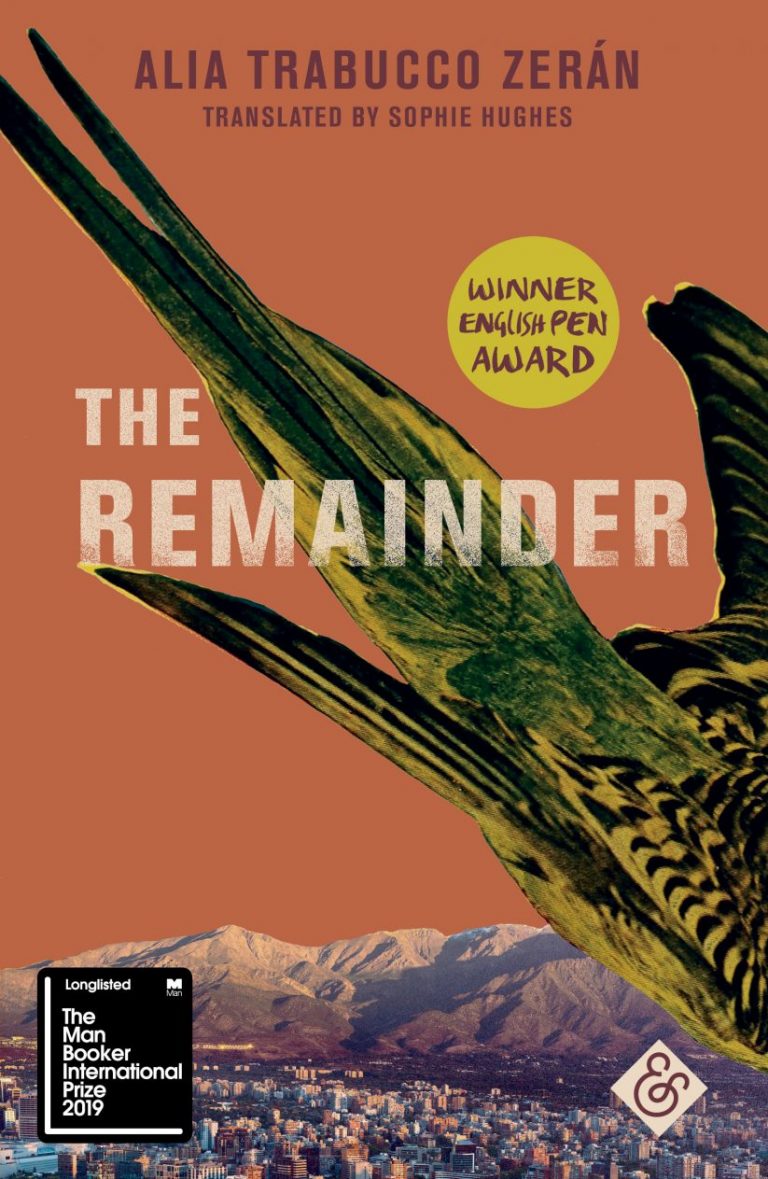

Alia Trabucco Zerán – The Remainder (Translated by Sophie Hughes)

29 April, 2019Alia Trabucco Zerán’s Man Booker International Prize-nominated novel, The Remainder, is a disconcerting road trip with a twist, which shifts between different time frames, voices and countries.

Iquela and Felipe are the joint narrators. Felipe sees dead bodies everywhere and is obsessed by counting them down (‘because adding them up is a big mistake’) in chapters that start at 11 and count down to zero. His prose is strung together punctuation-free in confusing and disturbing bursts. The bulk of the story is from Iquela’s point of view, narrated in numberless ( ) chapters. Iquela works as a translator and nervously dreams of leaving Santiago but is trapped in the city by her mother, who demands daily phone calls and visits.

Iquela’s quiet life is kicked into action by the arrival of Paloma, who grew up in Berlin after her parents fled Chile during the dictatorship. Their relationship is beautifully written: Iquela feels ‘as if I’d taken a non-existent step on the stairs’ when they meet at Santiago airport. Paloma has returned to Santiago to repatriate her dead mother’s body. When a sudden cloud of ash covers Santiago overnight (somehow this seems to be a non-event to the majority of the city’s residents), Paloma’s mother’s body goes missing. The three characters set off on a weird road trip, comically squashed together into the front part of a hearse as they drive to recover Paloma’s mother.

The reader never gets a clear picture of exactly how Iquela, Felipe and Paloma’s family stories fit together, partly because the characters themselves don’t have the whole story either, piecing it together from their own hazy childhood memories and fragments of their parents’ memories. The novel dwells on the idea of ‘unremembering’ – is it possible to remember, or forget, something your parents lived through? This theme reminds me of the Brazilian film Unremember (2018, directed by Flavia Castro), which also focuses on the inherited trauma of children of ex-militants, this time set in Brazil after the Brazilian dictatorship.

Memories are deceptive, and in this novel language itself is deceptive too. Santiago is covered in ash, but ‘Nothing’s blazing. Nothing’s collapsing. Nothing’s burning.’ Iquela’s parents and their friends have two names each from their militant pasts: ‘Those doubles of our parents from back before they were parents’. Paloma, who grew up in Germany, struggles to unlock the cryptic language of militancy: a ‘rat’ wasn’t a ‘rodent’, a ‘movement’ wasn’t an ‘action’ and ‘the front’ wasn’t the opposite of ‘the back.’ It’s testament to Sophie Hughes’ excellent translation that cryptic Spanish passages seem just as cryptic in English. Hughes cleverly translates Paloma’s awkwardness in Spanish (her second language) into funny turns of phrase in English too. The reader can’t help but notice Zerán and her characters’ obsession with language. Ellipses are used to cram extra descriptions in to Iquela’s narration, providing a three-in-one effect. Why settle for ‘go home’ when you could also have ‘return’ or ‘repatriate’?

The Remainder is a quirky and haunting novel, beautifully written and with a hypnotic queer eroticism that runs through the narrative. The story is funny, then sad, then morbid (don’t ask what happens to the green bird on the front cover) and it deserves its spot on the International Man Booker Prize longlist for 2019.

You can read the first chapter of The Remainder here and an interview with Alia Trabucco Zerán here.

The Remainder is published by And Other Stories. Alia Trabucco Zerán will be discussing the novel at London’s Rich Mix on May 15th.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.