Saying Yes To Chilean Rights: Pablo Larrain’s No

19 October, 2012For a man whose wealthy parents are both members of Chile’s right wing, Pinochet-admiring political party the Independent Democratic Union (UDI), the director Pablo Larraín’s trio of films set during military rule in the country have carried strong anti-dictatorship tones and no doubt caused much discussion at dinnertime in the family home.

The first of these was 2008’s Tony Manero, in which a Saturday Night Fever-obsessed psychopath prowls mid-seventies Santiago, with his every insane act rooted in deranged idolism of John Travolta’s hip-swinging funkster. Set against the backdrop of the dictatorship, the protagonist is a product of his environment, his sudden, random acts of extreme violence mirroring those of the state, as burly men in sunglasses yank people off the street or from their homes in the middle of the night to be questioned, tortured or disappeared. It is an unnerving portrayal of a society whose superficial coating of blinkered validity and tacky TV shows is riven with deep undercurrents of fear and oppression, yet it also drips with black humour of the bitterest kind.

2010’s Post Mortem also centres on an unhinged individual, again played by Chilean actor Alfredo Castro who reprises the sullen menace of Tony Manero, channelling it this time into the character of a morgue attendant during the bloody events of the 1973 military coup and the death of a president. As events unravel and an overthrowing becomes a massacre, he remains chillingly passive against the bloodshed and terror of the coup and its aftermath until the film’s genuinely shocking conclusion. Like Tony Manero, this is a film crusted in gloom, a world in which colour and self-expression are choked out of everything by the unrelenting circumstances of the time.

There are many similarities between the two films in terms of content, style and casting, but Larraín’s latest film No is of a different ilk. It is the quirky uncle to Manero and Mortem’s greasy sisters and it’s deviation from its predecessors is noticeable from the off. Castro is still in attendance but this time is relegated to a supporting role, with Mexican superstar Gael García Bernal taking the lead role. Garcia’s presence in No is a massive, err, coup for the small but burgeoning Chilean film industry and the actor’s role in the film has gained widespread interest, causing much excitement in Chile, giving No far greater international appeal.

The film’s title refers to the 1988 national plebiscite in which the public voted whether to continue with military rule or return to democracy, with a simple ‘Si or No’ choice. García Bernal is René Saavedra, a TV adman charged with orchestrating the televised ‘No’ campaign in a schedule that sees both sides receive fifteen minutes of nightly primetime in which to promote their message. Castro is René’s villainous colleague and rival on the ‘Si’ team, seeking to convince the Chilean public of the benefits of staying with Pinochet and showcasing the mass-murdering torturer’s cuddly side.

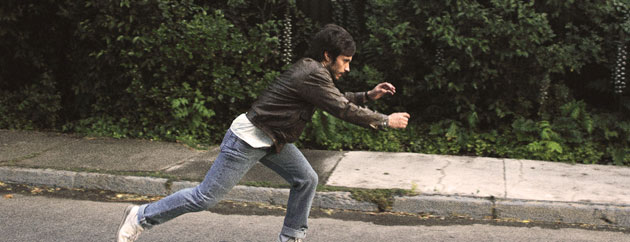

No takes a docu-drama format, splicing the narrative with footage of the time, including the real advertising campaigns. In order for the eighties imagery to be realistically merged with Larraín’s direction, a high level of authenticity is required. The cast are kitted out with typically naff period clothing, but Larraín largely goes about this by shooting the film in shaky, grainy handheld format which is far removed from the mounted cameras and moody filtered light of his previous films. It works to an extent in that it brings a gritty realism to proceedings, yet at times its self-consciously amateur style grates. This technique does fit more comfortably alongside archive shots of protests and interviews, although whether this is the reason for the handheld style or if it’s because García Bernal’s fee meant there was nothing left to spend on proper cameras is unclear.

The film is in turns sprightly and serious, its weighty subject matter offset by the general silliness of the late eighties. As René becomes more entwined in the future of Chile, he becomes deeply aware of the high stakes and of what some will resort to in order to get what they want. Chile is a country beset by fifteen years of fear, and silent menace still broods heavy in the shadows. Yet in spite of the secret police, the teargas and the shoddy jackets, there is an optimistic air as millions of people see light at the end of the long, dark tunnel.

It may sound obvious but No is a very Chilean film. Its dialogue is delivered in impenetrably thick Chileno, and while its topic represents a monumental moment in the nation’s history, in comparison with the tragic drama of the coup it is a lesser-known story to the wider world. However, thanks to the combination of compelling archive images, the offbeat direction and some subtly nuanced performances, this provides an intriguing account of the times. Larraín largely stays away from the conventional sense of fear or despair that is a common feature of dictatorship movies, and instead focuses on the shared strength of the Chilean people, injecting his film with a strong sense of hope and pride. The result is a powerful and moving, albeit slightly flawed, film which opens a window to one of the definitive points in the restructuring of the modern Chile, and a nation’s determination to stand up for its rights. I’d say yes.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.