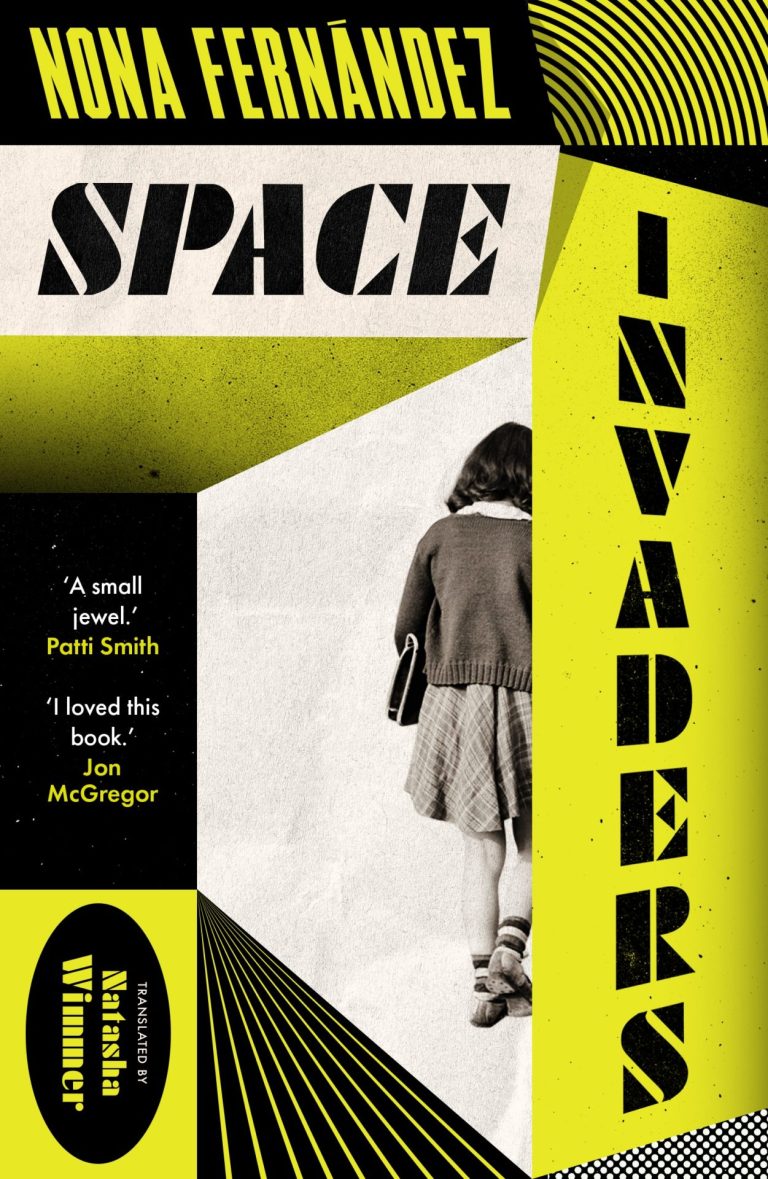

The Complexity At Remembering Chile’s Dictatorship at the Heart of Nona Fernandez’s ‘Space Invaders’

18 August, 2022The epigraph, “I am at the mercy of this dream: I know it’s just a dream, but I can’t escape it” really sets the tone for Nona Fernandez’s 80 page long novella Space Invaders, which is sensitively translated by Natasha Wimmer. In the book dreams and reality collide and merge, highlighting the complexity of the Chilean collective memory of the Pinochet regime which lasted some 16 years.

The recollections, or rather the semi-lucid dreams of a group of teenagers who grew up in the early eighties, make up Space Invaders. The subject of focus in all these dreams is an enigmatic young girl named Estrella Gonzalez; daughter of a mysterious, one-handed police agent, she is a moth of peace who strangely goes missing one day in 1985. It is later revealed through the naïve collective voice of the teenagers, that Estrella’s father shamefully murdered two communist militants and went into hiding, only to be arrested and put to justice in 1994. Estrella furthermore is murdered by a policeman one day in 1991 but like an angel, she “summons” each of the teenagers at night and haunts their dreams, taking them back to their childhood. The use of the present tense throughout the book really confirms the fact that the teenagers, now “alone and aeons older”, are harassed by their memories and live with them forever. The fact that Estrella appears to Zuniga “naked” and “pretty”. She always looked pretty with “black hair soaked with seawater” gives her the air of a siren tempting him out of his slumbers and tantalising him. The image of her cemented in her adolescent body and conveyed through her naïve letters, signed off with an enigmatic asterix only serves to heighten the severity and sinisterness of the Pinochet regime. Other ambivalent and ambiguous symbols like the Virgen del Carmen, the Chilean flag in the primary school and the Red Chevy driven by Uncle Claudio are given new meaning when looked back on by the adults who, only in retrospect, can understand the dark shadows they cast over their classmates. The books many short chapters and passages read like individual dreams and they give the book the feeling of a restless night’s sleep; in one section the kids play a game with the lights turned off in an abandoned classroom where the aim is to find the others crush to embrace and kiss. The sexual tension and frantic nature of the game reads as an erotic wet dream which harshly clashes with the intense nightmares of Estrella’s house, full of locked doors and cabinets of wooden hands: “Riquelme feels them exit the cabinet and come after him. They menace him. They chase him”. The use of the present tense and such vivid descriptions from Fernandez allow the author to convey the sleep paralysis or PTSD that affects a great deal of Chileans whose formative years were shrouded in doubt and suspicion. The fact that each teenager dreams in a different way only strengthens this sense of a Chilean collective memory. Fuenzalida for example, is “an expert in voices” so hears Estrella’s innocent tones and the aggressive hum of the Red Chevy. Maldonado on the other hand has “dreams constructed of words” and reads Estrella’s helpless letters in which she talks of her forbidden crush for Zuniga, a character whose parents are kidnapped by the secret police for protesting.

At a key moment in the book, after “Zuniga got into politics”, the silence and mystery surrounding adult themes in the book erupts into a deafening clamour. Suddenly, Nona details the “funerals, coffins” that were suddenly everywhere and how Donoso and Bustamente were beaten to an inch of their life by the police. The kids lose their innocence, and the reader learns of the harsh realities of a regime in which it was frighteningly easy to become a target of repression. This, however, is paired with the space invaders motif, which named each chapter after stages in the game (first life, second life, third life, game over) and the continuous intervention of Estrella who, as the teenagers become older and lonelier, only gets younger and brighter. The book is tantalising and troubling in every sense. Nona Fernandez uses Estrella Gonzalez to illustrate the contradictory nature of memory and prove that as Calderon de la Barca famously wrote, that life “is a frenzy, an illusion, a shadow, a delirium, a fiction. Is a dream and dreams are only dreams”.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.