Lisandro Meza: Legacy of a Cumbia Kingpin

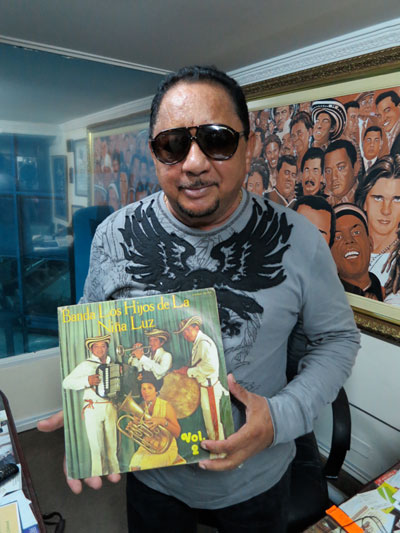

07 May, 2014“No, no, we’re inside the Gran Centro, not next to it!,” Lisandro shouts to me over the buzzy loudspeaker of my pirated cellphone, on a sweltering cab ride in sunny Barranquilla, Colombia. I quickly prompt our grumpy cab driver to take us to the Gran Centro shopping plaza that we had passed a few times before. Upon arrival, I find Lisandro Meza and son, Lisandro Jr., patiently waiting for our interview inside the Meza family recording studio and record label offices at Café Records. The 20-foot portrait of the man himself — hung proudly and prominently in the studio foyer, posing with his iconic Italian Castiglione-brand accordion and with the words “Lisandro Meza: El Macho de America” in large bold lettering — further indicate that we had indeed arrived. Cool and collected, sporting aviator shades and a casual grin, Lisandro Meza invites us in for coffee and conversation in his master office.

With a musical career spanning a half-century and change — or, 56 years for whoever’s counting — tropical accordionist Lisandro Meza embodies the spirit and evolution of popular Colombian coastal music: from its folkloric roots to commercial global crossover. His gifted virtuosity on the diatonic accordion and penchant for mixing Latin music genres are the foundation of his success. But to most, Lisandro is popularly known for his signature sabanero approach to the celebrated Colombian cumbia — a blend of Antillean, African and Indigenous Colombian musical influences, set to an infectious, syrupy 2/4 beat. Throughout his lengthy musical tenure, he’s recorded and redefined porro, cumbia, guaracha, banda, gaita, salsa, afro-beat, and, not surprisingly, even dabbled with a little reggaeton these days. And yet, this mixing of styles, reinventions of the traditional with the popular, is new as it is old when it comes to Lisandro’s musical method.

With the help of his father, Lisandro cut his first record at age 15 — some seven months after he secretly taught himself to play the accordion. For 14 years, near the start of his career, he was the star accordionist of famed Colombian supergroup “Los Corraleros de Majagual” — Discos Fuentes’ golden pop-tropical group of the 60s and 70s. He’s played and worked with a Colombian “who’s who” of popular recording musicians — from famed cumbia composer Calixto Ochoa to international vallenato-pop superstar Carlos Vives — and countless singers, musicians, producers and entertainers from around the world. Since then, he has continued to score hits well into the 80s, 90s, and 2000s with his family band, Banda Los Hijos de la Nina Luz, earning one of the biggest cult followings in cumbia-fervid Mexico, Central America, and parts of the American Southwest. Today, his accordion prowess can be felt the world over from Monterrey to Luanda, Los Angeles to London, and his classics continue to thrive by a new generation of digital DJs and remixers spanning North and South America.

Maestro, when and where were you born?

I was born September 26, 1939, in the Department of Sucre, located in the northern part of my country, Colombia. I’ve been a musician for 55 years, and thank God, I am still popular today. I was an integral member of one of the biggest groups of Latin America, after Cuba’s Sonora Mantancera, that is: Los Corraleros de Majagual. I’ve recorded 41 LPs with them — well, 41 “discographical works” [LPs, EPs, 45s, tapes, etc] — and with Lisandro Meza y Banda Los Hijos de La Nina Luz, my current group, I’ve recorded some 121 “discographical works” all together.

I am one of the original composers and singers of cumbia, porro and paseo; of all these things that today, musically speaking, we can say represents the vast sounds of Colombia.

Can you describe to me your childhood. What were some of your first musical influences?

Well, my dad had a little ranch in El Dificil, Department of Magdalena, where my parents had a sawmill in which they harvested wood for roads, various constructions and so on. One of their workers there had an accordion, and his name was Pedro Socarras. So he had his accordion, and like the badly behaved kid I was, I would hang out at the workers’ camp out there and beg him to let me play his accordion. Of course, he didn’t want to, because with good reason, he thought I might damage it. I was just this little kid, see?

But, like a good little Colombian, I made this little picklock, and I picked open the accordion case. (Laughs) I took it out and there I would dabble with it… just play around with it when he was gone to work at the sawmill. In those days, I practically taught myself how to play. Later, when I thought he was going to return, I would put the accordion back just like I found it, with nobody the wiser.

I did that for about a month. And the people would say, from the folks out there who lived nearby, that Pedro had some sort of “devil’s spell” on his instrument, because his accordion would play all by itself when he wasn’t there! (Laughs) Anyway, one year my dad threw a Christmas party for the workers, and Pedro got really drunk and passed out, so I grabbed his accordion and started playing it in front of everybody, and from there everyone discovered that I could play the accordion. My dad then bought me my first accordion, and seven months later, I recorded my first record. It all happened very quickly…

What was that recording?

“Aroma de las Flores.” I was 15 years old.

Wow. And for which record label?

Discos Tropical of Barranquilla. I also recorded with Los Vallenatos de Magdalena around that time, which included Anibal Velasquez: a well-known accordion player from here in Colombia. He was, and still is, a fantastic accordion player. He started playing before I did, and was very adept at a young age. But, see, I actually recorded the guaracha rhythm on the accordion before any of my musical colleagues here in Colombia, even before Anibal [Anibal Velasquez is known for his brand of accordion-driven guaracha, a typically fast style of the Colombian porro]. He was faster and better, but nowadays I can keep up with him!

When did the accordion start to become popular in Colombia? Was it common to hear or see when you first started playing?

Well, I’d say it first became popular around 1959 or so. That is: it had already been around for some time by then, see, but that’s when you started to hear it more prominently. See, it was Alejandro Duran’s vallenato style on the accordion that made it more fashionable. But see, of all of these well-known cumbia musicians, Lucho Bermudez, Jose Barro, who have made some of the best cumbias in Colombia – Alejo had the most precious style of all of them. He was very good.

So Alejo had a major influence on your style?

Oh, yes! He was the first “King of Vallenato.” I learned much from him; he was practically my professor. He was so sweet. He’s since passed away, but he had a pure Colombian heart, and no matter where you go, people still love and sing his songs.

When did you first start to play with Los Corraleros de Majagual?

It was, hmm… 1965. In ’65, I first recorded with Los Corraleros and replaced Alfredo Gutierrez, who was one of the founders of the group. See, I changed the style of the group. I put in an ‘international’ pop flair, which ultimately broke all the previous record sales of the group. I was with that group for 14 years. Afterwards, I retired from that group and created my own, which I still have today: Lisandro Meza y Los Hijos de La Nina Luz. With this group, I’ve traveled the world over. We’ve been to Africa, Europe, Central America, the entire Southern Cone — we’ve been a very blessed group.

Right. And how did you first get to know Antonio Fuentes (founder/chief producer of Colombia’s famed Discos Fuentes label)? Did you have mutual friends?

Well, see… Los Corraleros, via Antonio Fuentes, called me one day to see if I would be interested in replacing (main accordionist) Alfredo Gutierrez, as it so happened. So, I told him I wasn’t able to fully replace Alfredo—since I wasn’t as technically skilled as he was on the accordion — but that I could come in and bring in some different element to Los Corraleros: to make it my own. So, Antonio asked me, ‘What if we change the core sound of Los Corraleros?’ And I said, ‘Well, I don’t know if I can change it alone, but I will add my style, and together we can make it better.’ So we did. And it was a great success.

He [Antonio] did a lot of the arrangements on those early Corraleros records, right?

Yes. He did something very different: he added the electric bass. Before, it was like one of the little Mexican bass guitars, which you’d have to amplify it with a microphone. But then he added that, and well, it took off! Take “Suéltala Pa’ Que Se Defienda” for example… (Lisandro launches into the intro part of the song) ‘Suéltala, pa’ que se defienda/Ba pa pa pa/Suéltala, que ella baila sola…’ Well, see, that was a big, loud party song — it took off and became a huge hit!

Definitely one of my favourite Corraleros tunes! We were talking earlier about your youth, influences, etc. Were there any radio stations, or perhaps songs in particular, that you remember well?

Most certainly. See, I’m an ancestral musician. My grandmother sang pajarito music (little bird); you know, just acapella style, using only handclaps, improvising. And they would record songs like that back then, you know. And my uncles would play early gaitas, so for that reason, I come from a musical family. And of course, they would play with early folkloric instruments, not electric instruments. That’s why I tell people this family has music running in its veins!

In your words, can you describe to me what is “musica sabanera”? And how do you incorporate it in your music?

Let’s see, how do I put this? There are three different accordion styles here in Colombia: vaquero (ranch-style), provinciano (provincial), and sabanero (of the Sabana region). Mine is sabanero. Los Hermanos Zuleta are provinciano. Pacho Rada, of the Magdalena Department, is more of a vaquero style.

Vaquero meaning ‘vallenato’? I suppose that makes sense. Your music certainly doesn’t resemble vallenato style.

Right. See, there’s this Vallenato Festival in Valledupar. It really caters to the local sounds of the area: vallenato, or vaquero style. They’ve never crowned me king of the festival (which happens every year) because I come from the Sabana. Hence, I have that ‘Sabanero’ sound. So, all that we do here in the Sabana — including our take on the cumbia — is totally different. The Sabanero (musician) plays a bit longer, because he plays the slower cumbia and porro styles, and all in a minor key. Vallenato, on the other hand, is always played in major key. So, when you hear cumbia, paseo or porro, it’s different, because that’s our sound. The (Colombian-style) son is from the Magdalena region; the puya stems from the black rhythms of the Palenque and Sabana regions. I’m the creator of a puya song called “La Upa Ja!,” it’s a fantastic puya. It always goes over very well at the Vallenato Festival.

So who else would be identified as a ‘Sabanero’ accordionist? Someone like, Andres Landero, for example?

Yes. And Alfredo Gutierrez, Anibal Velasquez. Everyone from this side of the Magdalena River are sabaneros, and those on the other side are vaquero and provincianos.

I wanted to talk to you about your Salsita Mami LP on Discos Fuentes. Can you expand on this salsa-cumbia hybrid sound that came from this record? It’s really quite a ground-breaking recording in your catalogue.

Yeah, it’s a good one! When we made that record, Discos Fuentes was really a versatile label at that time—they were producing all kinds of different Latin styles. So they asked me if I would make a salsa record, since I had a few salsa songs I would play out at that time. Salsa was becoming very popular at that time, see? So, I said, ‘sure.’ But sing those songs myself? No. I told them if they could find a good salsa singer, then yeah, I’ll lend my name to it. Because at that time, I couldn’t really sing salsa that well, it was very new to me. So I did most of the arrangements, but I wasn’t singing on that record.

But you know, after that, I learned how to sing salsa! And I started playing salsa with the accordion—imagine that! So, you know how I told I couldn’t be crowned king at the Vallenato Festival because of my sabanero style? Well, then I started to mix in salsa with my sabanero style, to create something different than my contemporaries. This is how I compensated with not playing vallenato: I created a new genre!

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/67322565″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_artwork=true” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Speaking of vallenato, it seems to be a very dominant genre within Colombian music, even though there are many different styles and genres. You’ve touched on this a bit, but why do you suppose this is? Considering that vallenato became more popular in the late ‘70s, significantly later than others popular Colombian genres.

Well, see, vallenato really is a beautiful music. There are many vallenato composers that have made some truly wonderful songs that have lasted the test of time. But, see, the problem is that reporters, or even some so-called “vallenatologists”, will come in here and say they know all this stuff, and that they know more about it than me! They’ll say, ‘oh, this is paseo, they way he sings…’ and they say all this technical jargon, like they created the genres! So, there just came to be this focus on the Valledupar region as the founding of modern Colombian music. And they (the press) only cover a small percentage of Colombian composers. So, you know, just like in the Vallenato Festival: it all revolves around this regionalism in Colombian music. (Pauses, sighs) Well, so be it…

I see. I wanted to talk to you a bit about your record label: Limeza Records. When did you start it?

(Points at a red wax LP, framed on his wall) That was my first recording on Limeza! It was, hmm, 1970.

And that was here in Barranquilla, right?

Yes.

By that time, didn’t a lot of the original coastal-based record labels uproot to Medellin?

Oh yeah. Discos Fuentes was founded in Cartagena, you know? But, just like women tell us to do, we do it! (Laughs) Antonio Fuentes’s wife was a cachaca [slang word for people from the interior, i.e. Bogota and Medellin]. See, she wanted to move back to Medellin, so he took the label and moved it there! So there was Fuentes, Sonolux, Codiscos, Metropolis…all those labels were there in Medellin. So you know, a lot of the times we had to go from here to Medellin to record. The only one that stayed behind in Barranquilla was Discos Tropical.

Hmm, so just two labels in Barranquilla, Limeza and Discos Tropical?

Well, no. Limeza at that time — see, I could fit it all in my pocket! It was a small operation back then, we weren’t a major label or anything. It was my operation, but after Fuentes left, the rest of the labels left, too. Now I have Café Records, for about 6 years now. But when the music pirates came, it was like, ‘eesh!’ It’s hard, you know? It’s hard to make records these days. See, there in the United States, it’s better: they respect the copyright laws there. But man, it’s hard here.

Right. Here, you can find your CD selling in the street right after you record it!

(Laughs) Yeah, that’s right!

So how many records did you put out on Limeza?

Two LPs.

Just two? And a lot of 7” singles, right?

Yeah, later we put out a bunch of singles.

It seems to me that your most popular 7” single on Limeza was “Shacalao” (a funky cover of Fela Kuti’s “Shakara”).

Yeah, we cut that here in Barranquilla—at Discos Tropical’s studios—then released it on my label. We did a totally different rhythm with that record, you know? It was so unlike anything you would hear from here. Man, I didn’t know what I was singing with that record. It sounded like nonsense to me! (Laughs) And I would ask the studio engineer: ‘Uhh, well how does that sound?’ and he would say ‘Well, it sounds just like you think it does!’ (Laughs) The phrases I sang didn’t really make sense but I guess you could understand some of it. What a fun record, though.

So, “Shacalao,” we later heard, did very well in Europe and Africa! And I got a new audience there in Africa, but they also love my cumbia records there, too. And when we went to go tour there, people would ask me for my autograph: it was incredible. But goodness, it’s very poor over there. But you know, that’s where our music comes from in Colombia. The cumbia owes to the African drum, the tambor—it’s an African rhythm, you know?

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/11829981″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_artwork=true” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

For sure. So it was your idea to record “Shacalao”? Judging from the amount of Fela covers that came out of Colombia in the 1970s, I get the sense that his music was quite popular here.

Yeah, see, there was a lot of music coming into Colombia from Africa. It was becoming popular at that time, from the “picos” (soundsystem DJs of the Caribbean coast). So, yeah, I decided to record it. But it was definitely a bigger hit in Europe and Africa than here, I think.

Right. You mentioned earlier the “picos” of Colombia, and I know they were very important in popularizing African and Afro-Colombian music throughout the coastal region. Can you speak on your relationship with these DJs?

That’s right. I’ve always had a good relationship with them—they’ve always supported me. Songs like “Juventud Flaca y Loca,” “Acordeon Pitador,” “Las Tapas,” which was a big cumbia hit at Carnaval—they would play those songs a lot. But, you know, musically speaking, Barranquilla is like a whole other country within itself, because of all the different musical influences you find here. There’s a lot of champeta, criolla. But, I try to make music that the whole world can enjoy; it doesn’t cater just to the coast. They really like the fast paced cumbion sound here in Barranquilla.

I understand you have a big fan base in Mexico, and I’ve even heard you call out your fan base and the sonideros (Mexican soundsystem DJs) in your later records. Can you speak on that?

(Laughs) Yes, it’s true! See, I’ll cut a cumbia record, and I’ll shout out to the DJs and people there in Mexico. It’s a way for me to say ‘hello’ to my friends there: the people who support me and still love my music. So I feel it’s important to talk directly to them.

Sure. So, are there any new styles of music that you mix into your music these days?

Yeah, for sure. Like now I just cut this cumbia that I mixed with reggaeton. But, I’m just trying to make that good tropical music—dance music, you know? Sometimes you have to keep up with the times, you have to cater to what’s new. That’s what I’m after, though: whatever sounds good.

Well, I won’t take too much more of your time. It’s been truly enjoyable to sit down and talk with you today. So, let me close with this: What is it you want people to remember about your music, about your legacy?

Sure. I mean, when I see people in the street, or people come up to me when I’m out, they’re always nice and respectful with me, and tell me how much they love my music, or what I’ve done for them. That’s so important to me. When I travel outside of the country, people treat me like an ambassador to our Colombian music. And thank God, my music has sold the world over, and that makes me happy. I just want people to recognize me as an artist. You know, just to be remembered as a good father, a good son, a good musician. And someone who had respect for his fellow countryman, someone who loved art and music, and someone who lived his life in the name of the Lord. As someone who said: ‘yes’ to life, and ‘no’ to drugs.

I’ve always had respect and love for Colombian music: for cumbia, paseo, porro. I hope people will remember that I produced and created our beautiful music here in Colombia!

All photos by Adam Dunbar

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.