Ropa Sucia: Rolando Rodriguez’s Magical Renditions of El Salvador, L.A. and Self

14 May, 2018Rolando Rodriguez’s solo exhibition Ropa Sucia at the Jean Deleage Art Gallery at Los Angeles’ Casa 0101 Theater was a two part theatrical exposure influenced by magical realism. A play between words, ideas and objects, his three-pronged exhibit consisted of video, a clothes line installation and photography, a multi-conceptual approach to his creative process.

Ropa Sucia (dirty laundry) journeys into Rodriguez’s rite of passage which, through the language of clothes and vernacular Salvadoran expressions, examines his Latino identity and traces his family’s history. Rodriguez is a contemporary Los Angeles-based artist, film-maker and writer. He’s earned a degree in architecture from Columbia University in New York City. His directorial short films have debuted at the Outfest LGBT Film festival in Los Angeles.

The fictional character in his photography is Rodriguez himself. The invention of these characters is Rodriguez’s way of mediating between the real and the magical. In his series of self portraits he shares his desires, dreams and struggles. In a chronological installation, he begins with what can be interpreted as self displaying subliminal colorful messages of breaking away, of his childhood in South Central Los Angeles, and what it means to be a young Latino queer. A glamorous red glitter Dorothy shoe filled with green grass [pictured below] is Rodriguez’s special hint to the world he belongs to and cares for. He unfolds his sexuality like a delicate free flowing spring breeze.

There is a quest in his work that seeks clues to many of his unanswered questions. Balloons are a constant element in his photography; they have come to symbolize flight and voyage and can best be visualized in “The Great Escape” [2013, pictured below].

South Central Los Angeles is the playground setting of much of his photography. Rodriguez brings out the color of a community who for the most part have been under-served. In his 2013 image “The Apparation of the South Central Angel” [pictured below] Rodriguez addresses the duplicity between human and angel and, “how early on in our communities we learn from adults, particularly from teachers who live outside our neighborhoods and institutions that we have to leave in order to be saved.”

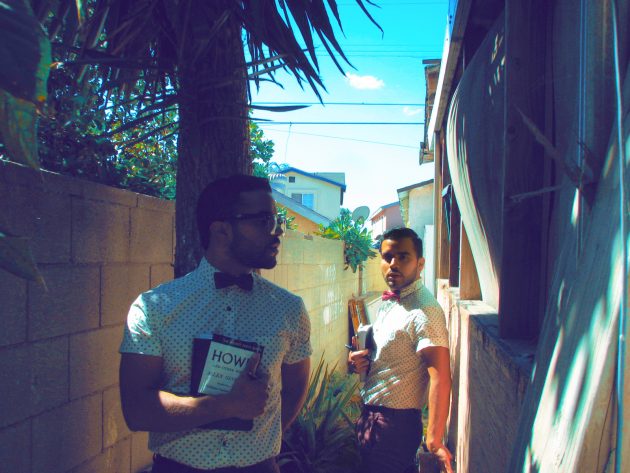

The suspended clothes line installation with bright intricate organic patterns not only accompanies his photography, but speaks of the duality between his male femininity as a dimensional branch to his otherness. In “The Council of Rolando and Malte” [2014, pictured below] the use of flower pattern shirts is Rodriguez’s queer exclamation mark. Through clothing Rodriguez makes a poignant statement: the language of clothes conveys social, gender, cultural and political connotations. For writer Alison Lurie the language of clothes is a way to converse.

His video installation of two TV monitors play two of his short films, one is a playful examination of the self throughout the streets of New York titled “Surrender”. The second “Malte Mara Mathe II” reveals a mystery whetr all is unknown and unchartered. The experimental film’s background sound of wind, of loose leaves whirling between each step, captures an unfolding drama tuned to the beat of Rodriguez’s quest.

Rodriguez guides the viewer through the interchanging meaning between dirty laundry (ropa sucia) and dirty war (guerra sucia). It is an explosive two word title that swivels and airs out secrets, truths and lies not meant to be known. His last act encompasses the role of memory as a referential recall that unites both past and present as constant historical cycles of tugs and pulls.

The transitional phase between the first and second act of his solo exhibition cherishes the diversity of friendships and the intimacy around family gatherings. He invites the viewer to a visual walk-through with images that bloom with all that is close and dear to him in the midst of his rite of passage. This transition is a step away for Rodriquez as the main subject leads him towards the other as an extension of I. This coming of conscious is expressed in his image “The Day he Saw Himself in Others” [2013, pictured below].

What begins to unravel in the second act is a turning point for El Salvador’s history: the dirty war known as La Matanza (the 1932 Salvadoran peasant massacre). This tragic incident would resonate with a personal link written on shredded white cloth pinned onto a clothes line with red stains and red letters:

Thousands upon thousands of indigenous people rose up and rebelled against inequality.

It was 1932 and the government killed them.

In a few years, my grandmother would be born but already “there were no Indians left in El Salvador.”

Those who survived threw away their clothes and no one would know THEY EXISTED.

R.R

Over the course of six days over 30,000 peasants and indigenous were killed by the Salvadoran government during La Matanza. Clothes as a social and cultural marker played a determining role for survivors of the massacre. After the 1932 incident anyone wearing traditional indigenous dress ran the risk of persecution and possible death. Survival now depended on the lexicon of clothing. Rodriguez’s clothes line is charged with a pulsing note that unveils the bleaching out of history from El Pulgarcito (AKA El Salvador); removing its indigenous roots.

“On Sale in America” [2018, pictured above] featured a light blue fabric softener plastic container alluding to the hard-wired U.S policy of intervention in El Salvador’s struggle for self determination (aka, the revolution) of the early 1980s. The fine print advertisement label on the container reads: Made in El Salvador, exported by bulk since the 1980s with terror funded by the United States. The selected font size of the label is intentionally small enough to go unnoticed. This surprising and subtle addition to Rodriquez’s art piece reminds the viewer and consumer of images, how western media and the entertainment industry function as the social fabric softener of public opinion/outrage to tie it to the desired outcome of U.S political and military agenda. Forced exiles from El Salvador to the United States, including his family, were victims of American aggression and its ‘American’ dream of conquering markets and exporting one way models that create economic dependency. For U.S Scholar Juan Gonzales the sudden exodus due to the civil conflict:

“Did not originate with some newfound collective desire for the material benefits of U.S Society […] they were a direct result of military and economic intervention by our own government.”

Next to the fabric softener is the second component of “On Sale in America”, a bleach container made in Los Angeles. The use of bleach is symbolic. It’s a form of erasure, bleaching out cultural singularities, removing color, retaining whiteness (code for privilege and access), the markings of colonization for the past five centuries. Stamped to the bleach product is a warning label that spells: “keep out of reach from children”, and slang words that reference popular vernacular Salvadoran expressions such as: cipote (child), guanaco (slang for Salvadoran), salvatrucha and mara (gang). What is it about this bleaching process that Rodriguez is singling out? Is Rodriguez saying “to be visible, one must become invisible at the same time?” And why is he emphasizing Made in Los Angeles?

What is hidden and often overlooked is the birth of maras as gangs started in Los Angeles, California. Some Salvadoran children and teenagers facing retaliation from local gangs were forced to create and start their own groups as a form of protection and compensate for the lack of belonging. There would be no warm welcome for refugees seeking sanctuary from war back at home.

The installation of the fabric softener and the bleach combination best describes a method of deleting memory and the subjection of people to the demands of a dominant culture; first soften then bleach. The question of identity via assimilation is tangible to race, class, gender and origins.

Rodriguez’s hanging of crucial vignettes of history on the gallery walls are stubborn revelations that refuse to be forgotten. His invented characters and his photography bring magic to his real world and the real to the magic. Ropa Sucia sprinkles bits of glitter onto our world.

Rolando Rodriguez’s Ropa Sucia was exhibited at Casa 0101 Theater, Jean Deleage Art Gallery in Los Angeles from February until April 2018.

Visit voglerbrigge.com to see more from Rodriguez.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.