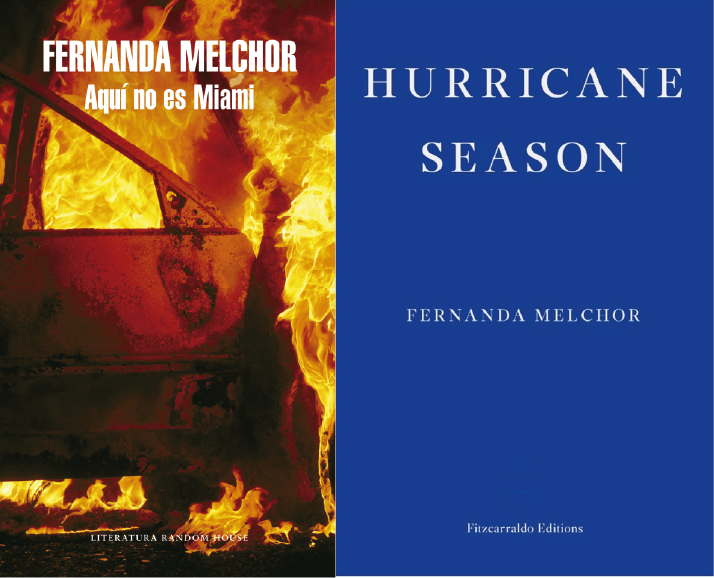

Fernanda Melchor Offers ‘Honest’ and Gritty Portraits of Mexican Society in ‘Aquí no es Miami’ and ‘Hurricane Season’

26 August, 2020The International Booker-prize nominated Mexican writer paints a picture of a dark and violent modern-day Veracruz by layering individual experiences in her collection of non-fiction narratives, Aquí no es Miami [This Is Not Miami] (2018), and her new novel, Hurricane Season (2019).

Aquí no es Miami (2018), Mexican novelist and journalist Fernanda Melchor’s first book of non-fiction, opens with a story from the author’s own childhood. A nine-year-old Melchor sees colourful lights in the night sky while at a beach near the Port of Veracruz, and knows that these belong to a UFO. She spends the rest of the summer obsessing over UFOs, staking out the night sky, devouring comics about aliens, and studying the documentaries of “UFOlogist” Jaime Maussan.

“Jamás en la vida volví a creer en algo con tanta fe como creí en los extraterrestes” [“I never again believed in anything as fully as I believed in aliens”]

It is only later, after overhearing conversations between adults, that she learns the sad truth: the UFO wasn’t carrying aliens, but rather hundreds of kilos of Colombian cocaine. The narco planes she saw that summer signal the start of a new era of drug activity in the region.

Beginning in the 80s and 90s, the Gulf Coast state of Veracruz saw the steady growth of an illicit drug trade, largely controlled by the Gulf Cartel and its notoriously brutal offshoot, Los Zetas (“The Z’s” in English). Since then, the state and in particular the city of Veracruz have become a battleground for cartels and criminal organizations. The escalating violence and corruption perhaps became most glaring in 2016 when then-state-governor Javier Duarte fled Mexico after being caught embezzling millions in state money and associating with criminal organizations. His name has become synonymous with corruption and impunity taken to an almost farcical extreme, and the toxic roots and implications of crime and duartismo are well-documented in the pages of Aqui no es Miami and Hurricane Season.

As in the story of the UFO, Melchor prioritises the individual perspective as she depicts the realities of her home-state, layering both everyday and astoundingly barbaric experiences framed by this political context. Her newest novel, Hurricane Season (trans. Sophie Hughes, 2019), which has been shortlisted for the 2020 International Booker Prize, attempts to tell a longer, unified story using this collage-like technique. At the centre of Hurricane Season (published in Spanish in 2017 as Temporada de huracanes) is the murder of a Witch in the small town of La Matosa, near the city of Veracruz, based on a real-life murder Melchor read about in a local paper (“Some of the events described here are real. All of the characters are invented,” Jorge Ibarguengoitia warns us in the epigraph).

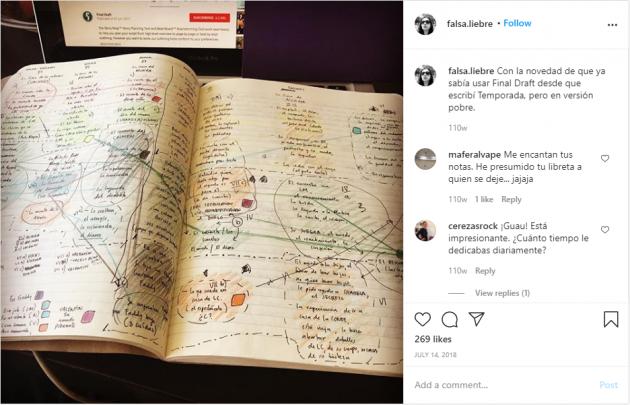

The book itself is made up of absorbing narrations from various intricately connected residents of La Matosa as they gradually offer up the context for and interpretations of this initial act of violence. Each chapter consists of continuous, tumbling blocks of prose told from a new character’s point of view, with no clear cuts between moments of dialogue, moments of recollection, and streams of consciousness. There is an intense oral and aural quality to the novel overall: it is dominated by voices and sounds, with the characters’ speech and thoughts only ever interrupted by the voices of surrounding characters or occasionally by music playing in the background (one devoted reader even made a Spotify playlist of all the songs that appear in the novel).

This, too, is a method Melchor had already finely honed in Aquí no es Miami, where some crónicas consist entirely, or almost entirely, of other people’s voices. The piece titled “La vida no vale nada” [Life is worth nothing] opens midway through a presumed conversation between the author and a friend, and registers every tangent, filler word, and moment of doubt in the speaker’s monologue about the time he was summoned to meet with Los Zetas. There is a sense that we are witnessing this conversation ourselves in real-time, or that we are listening to the playback on a journalist’s tape recorder. Above all, as in Hurricane Season, conversational language, swearing, and slang are rendered with a finesse that makes the passages mesmerising, smooth, and believable, allowing Melchor to shape entire characters through their voices alone.

As the narrators of Hurricane Season reccount their motivations and experiences in their given chapters, they implicitly reveal more about the town in which the murder has occured. Melchor’s La Matosa is an intensely brutal, forsaken place, where human life and dignity are worth very little. In our narrators’ monologues, we notice the near absence of love and the pervasiveness of violence in all of its forms. Sex is almost always abusive and depraved, while families, and indeed most relationships, seem to be based purely on resentment, necessity, or obligation. La Matosa is plagued by a host of social and political ills: poverty and disenfranchisement, machismo, trans- and homophobia, the failures of authorities and social institutions, substance abuse and the wider climate of drug violence. We see how all of these forces allow the Witch’s murder to take place, presenting a more nuanced picture of the central crime. With every chapter we appear to wade deeper into the town’s secrets, and to spiral closer to the truth.

Actually reaching this truth, however, is impossible. Crucially, we never hear from the Witch herself, and see her only from her neighbours’ points of view. A few chapters are composed entirely of anonymous gossip and hearsay, jumping between competing theories of what’s really happened and why. The powerful sense of evil and darkness at the heart of the novel inspires appeals to supernatural forces in many of these theories, obfuscating the “true” story we hoped to uncover even more.

This ultimate inaccessibility of the truth is reminiscent of another piece from Aqui no es Miami, “Reina, esclava o mujer” [Queen, slave, or woman]. This piece centres on a murder, too: the alleged murder and dismemberment of two young children at the hands of their young mother, Evangelina Tejera, a woman from a well-to-do family who, just a few years before, had been crowned Queen of the Veracruz Carnaval. The crime is reported on in local papers and is much talked about, becoming fodder for ghost stories and urban legends.

Here, as in Hurricane Season, Melchor ventures to learn more about the real figure of Evangelina, and about the context and implications of her story. She does so thoroughly: her first-person narration is constantly interrupted by news articles, legal and medical documents, music, and the words of people she interviews, from other journalists to regular city residents (Melchor can jump freely from one perspective to another, and her reader will follow, guided along by her slick prose and deft handling of any register a story calls for). The piece is not so much a hard-hitting journalistic investigation as it is a documentation of personal reactions to and speculations about this event, and what these reveal about a given society. It captures how events are turned into stories and legends.

The choruses of speculation and myth-making both here and in the novel attempt to fill the gaps left behind by the lingering mysteries of these deaths. This layering of rumours and superstition only underlines the fact that we cannot have a total, objective account of what happened to Evangelina and her children, or to the Witch.

Melchor’s writings accept the inaccessibility of truth and, in the face of this, embrace what we can access: the narratives individuals craft about the events they witness, however imperfectly. She is, above all, drawn to stories, to how stories come about, and, of course, to how they are told. As she says in the foreword to Aquí no es Miami:

“[Aquí no es Miami] fue escrito en un intento por contar historias de la forma más honesta que reconozco posible: aceptando este carácter oblicuo del lenguaje y aprovechandolo a favor de la propia historia. No importa que sea imposible ‘reproducir’ la realidad con una herramienta que deja las manos astilladas… las historias nacen en el lenguaje y en él alcanzan su sentido más profundo.”

[Aqui no es Miami was written as an attempt to tell stories in the most honest way I see as being possible: accepting the oblique nature of language and making the most of it by focusing on the personal story. It doesn’t matter that it’s impossible to ‘reproduce’ reality using a tool that leaves your hands full of splinters… stories are born out of language and it is through language that they gain their most profound meaning.]

Her narrative techniques, then, privilege people’s individual stories, and artfully preserve their registers, their tangents, their “I think’s” and “I don’t know’s”. With this dedicated capturing of words and voices, the writings of Fernanda Melchor honour the ways people experience the gritty realities of life in Veracruz.

Hurricane Season is available for purchase from Fitzcarraldo or New Directions. Aquí no es Miami is available for purchase from Literatura Random House. The English translation, This Is Not Miami, is forthcoming on New Directions.

You can hear Fernanda Melchor talking about Aqui no es Miami (in Spanish) here and here. See below for a reading from Hurricane Season by actor Toby Jones.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.