There Are No Normal Places: An Interview with Mexican Writer Juan Pablo Villalobos

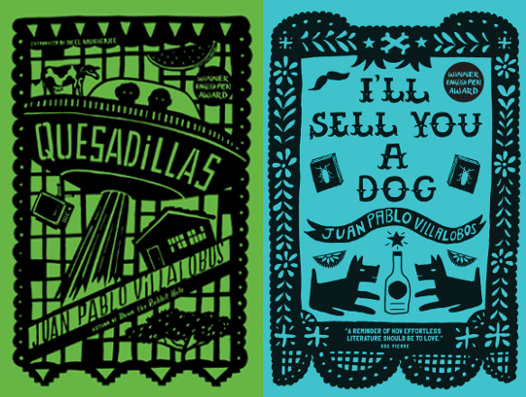

23 September, 2015Juan Pablo Villalobos, born in 1973 in Guadalajara, Mexico and currently living in Barcelona, is the author of two published books in English. Down the Rabbit Hole, a story told by the son of a Mexican drug baron, was shortlisted for the Guardian First Book Award in 2011. Quesadillas (2013) is a satirical take on class and corruption set in 1980s Mexico, and is just as funny as his first novel.

His most recent book, Te Vendo Un Perro, praised by DBC Pierre as “a reminder of how effortless literature should be to love,” will be published next year in English by And Other Stories as I’ll Sell You a Dog.

Villalobos, one of the guests at the 2015 FlipSide festival in October, spoke to Sounds and Colours about dark humour, Mexico, his literary relationship with his country and the (non)existence of ‘normal places’.

What is it like to write about Mexico? You once likened writing about your country as a ‘poisoned gift’.

Right now I’m in the middle of a kind of crisis, about my literary relationship with Mexico, because I’ve lived abroad for almost 12 years. In my first novels the distance I had with my experiences were an inspiration and they worked well for me. But now that distance is becoming ever more difficult to digest.

I’m starting to feel like I don’t understand my country. My country has changed so much in recent years that I can’t really understand what’s going on, particularly because what has been happening in Mexico is so horrible. I talk with my friends and family, asking them to explain to me what’s going on because I try to follow the news and read the papers but it’s not the same when you’re not there.

With my new novel, my first reaction was to try to write something different, maybe not located in Mexico. But I failed, so I’m working again on something about Mexico.

Your first two novels cover heavy subjects – violence, death, disappearances, corruption – narrated by child protagonists, who seem to be both insightful and ignorant. What was your intention?

I don’t believe in objective narrators; I think no one believes in that kind of narrator… In Down the Rabbit Hole, with this child perspective, I think that at the time no one had tried it, at least not in the Hispanic world. And that was a little new.

And I thought that the narrators’ combination of ignorance, knowledge and curiosity also had a funny effect. And as I’m a big fan of humoristic literature and dark humour, I think I had to write that kind of book.

Is it difficult to write a funny book?

Yes. Humour is an effect that obviously the writer proposes, but it is not complete until the reader gets the book and reads it. And maybe the reader will say it’s not funny. Henri Bergson said that there’s nothing worse than laughing alone.

Your second novel’s original title in Spanish is Si Viviéramos En Un Lugar Normal (If We Lived in a Normal Place). Can you explain?

I like to quote a song by Caetano Veloso that has the line “Up close, no one is normal.” Actually, the title saying ‘If we lived in a normal place’ for me was like a joke, but people often interpreted this title literally, like as if I were actually desiring that Mexico could be a normal place.

Because for me the idea was to be ironic, to say that actually there are no normal places. For me there’s this idea that Mexicans often have, we think ‘Ah, but this wouldn’t happen in Germany, in England, in the States. Because there, things are normal.’ But when you have the opportunity to travel and go to Germany and hear everyone say ‘Ah, this wouldn’t happen in another place’ too, then you discover that there are no normal places.

What about your third novel, I’ll Sell You a Dog?

The original idea was to write the story of a painter [Manuel González Serrano, 1917 – 1960] who was born in the same city as me, Lagos de Moreno,. This painter was the grandfather of a very close friend. He died aged 43, schizophrenic, on the street. It was a very tragic life. He was a genius and didn’t get recognised until 1999 when an exhibition was organised in a national museum.

I found that the way of writing this book was not talking directly about the life and facts of this painter… the painter is in the heart of the novel… but not the main character. He’s like a memory.

I’ll Sell You a Dog has been described as ’80 years of Mexico’s art and politics in one book’. How did you achieve this?

The main character is an old man called Teo, 78 years old, who happened to know this painter when he was young and remembers some episodes with him. He’s telling his life, the memories of the family: that’s 78 years. So the reader will know some of the politics and history of art in Mexico from the 1930s until now.

You’re interested in writers and artists who are ‘outside the canon’. What do you mean by this?

It has something to do with my new novel, because of these discussions about how, why and what do we as a society to accept something as a canon – the ‘good art’ or ‘good literature’ – the ones who deserve to be remembered and those we decided to forget.

Why do we remember Frida Kahlo and why don’t we remember Manuel González Serrano? Both are really good; it’s not about technical quality, about art. It’s about how we feel memory. Because I think what happened with this painter [Gonzáles] was that no one told the story of his life.

Is this a good moment for Mexican literature?

I think we’re in a very good moment internationally. I don’t think this means that it is any different from 20 years ago… Because 20 years ago I think maybe Octavio Paz and Carlos Fuentes were getting lots of international attention. But now many of us are being translated into several languages and it seems like there’s some kind of boom in Mexican literature.

Maybe also the horrible political situation in Mexico provoked the readers… because all this violence and terrible news makes people want answers and some of the writers of my generation are talking about these subjects, like narco, disappearances, corruption.

I think there’s a new generation of very good writers; I’m just saying that it’s not different from what was happening 20 years ago when we also had very good writers, but they didn’t have the possibility of being translated and published in other countries.

Juan Pablo Villalobos is a guest at FlipSide 2015, the Latin American arts and literature festival in Suffolk, speaking alongside writers Cristovão Tezza (Brazil) and José Eduardo Agualusa (Angola). More information at flipsidefestival.co.uk

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.