Mario Benedetti – Who Among Us? / Springtime In A Mirror

22 January, 2020I’ve always had a soft spot for Uruguay. I lived and worked in Montevideo for a spell, and spent a good bit of time exploring the interior, hanging around in the sleepy towns of Trenta y Tres and Tacuarembó for perhaps longer than was necessary – their relaxed pace of life seemed to chime with my own internal clock. I was always certain that Mario Benedetti, revered as one of Uruguay’s finest novelists, a documentalist of the minutiae of Uruguayan life, of the quotidian, of the emotional landscape, would be a writer I would love. Exiled in the 1970s during the military coup – his participation in the leftwing coalition Frente Amplio made this a foregone conclusion – his work is also tied with the political and social struggles that the country had faced. Surely, his voice would be the Uruguayan voice that would speak to me above all others, take me back to that provincial Uruguay I had fallen in love with?

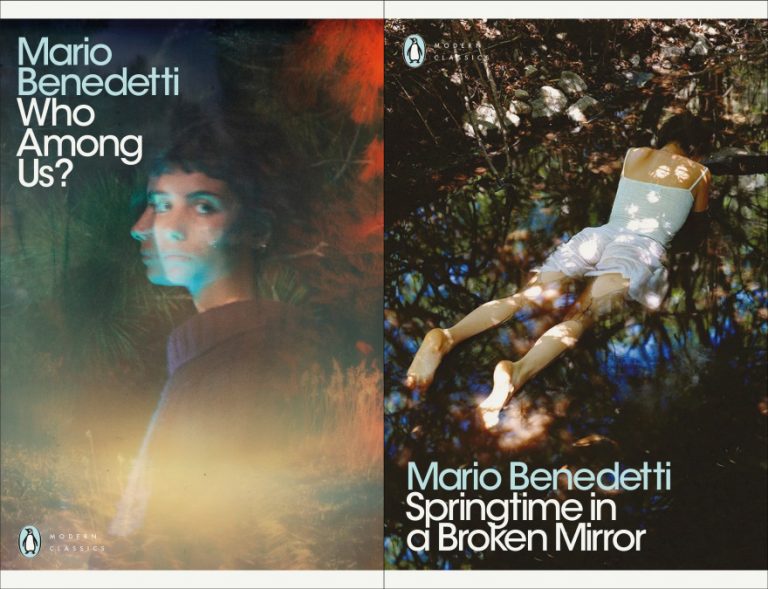

With the release of Springtime In A Broken Mirror and Who Among Us?, translated for the first time into English (by Penguin Modern Classics) this was my time to find out. Unfortunately, I found it to be a deflating experience.

Let me begin with Who Among Us? – which like the other has been translated by Nick Caistor, and is the shortest of the two novels. It tells the story of a love triangle: Miguel and Alicia met at school, becoming incredibly close, always there for each other, but then Lucas arrived. He was charismatic, impulsive, he offered Alicia intellectual nourishment, their conversations would become impassioned, often becoming heated. He lit a fire in Alicia which Miguel simply couldn’t. Yet, when it came down to it, Alicia decided to marry Miguel, with Lucas fleeing to Buenos Aires. The book begins down the line, Alicia and Miguel have two children but their 11-year-old marriage is on the rocks, not helped by the fact that Miguel has engineered for Alicia to travel to Argentina to meet Lucas, and all his old concerns have returned to the surface.

The novel is split into three parts: Miguel’s story, a letter by Alicia, and a fictionalised, poeticised version of events by Lucas. It is Miguel who dominates the story, his words full of self-pity, he never quite knew why Alicia married him and not Lucas, and this has haunted him ever since, to the point that he’s now pushing Alicia away. Curiously, Alicia’s own story, which is in the form of a letter to Miguel, leaves many of the questions unanswered. Only taking seven pages of the book, it does little other than address what we already now, that Lucas has more charisma and that 11 years of a marriage with very little emotion has left her wanting something more. It’s followed by Lucas’ own version of events, which is a told in a very round-about way, an overly-intellectual attempt at romance, which comes across as cold. As a whole, it’s a simple story, with its drama in the emotions of the narrators. It uses an unconventional way of telling the story, but without warm characterisation and a narrative which barely moves, it feels like a story over-playing its superficial nuances, instead of digging deep into the lives of its characters.

Springtime In A Broken Mirror has a similar approach, and again features a love triangle at the core of its story, yet it is about a broader story. Set during the military dictatorship it is the story of Santiago, a political opponent of the government being held in a Montevideo prison. Chapters alternate between his turmoil from behind bars, the thoughts of his wife Graciela who has slowly become distant from Santiago and fallen in love with Rolando (Santiago’s best friend), the thoughts of Santiago’s father as he tries to deal with knowing about Graciela and Rolando, the more innocent thoughts of their daughter Beatriz, and other passages that tell about this affair, as well as the stories of exiles. It’s the last of these that feels the most ground-breaking, Benedetti adding in short stories of people exiled, including stories of himself, which offers a break from the very claustrophobic story of Santiago and Graciela, while also opening up the novel to a broader environment of what was happening at the time, akin to breaking the fourth wall.

As with Who Among Us? I felt frustrated by the narrative arc and the building of the core story. The emotions of the main characters rarely seemed to develop – with even Santiago’s admission of doing a terrible thing to one of his cousins, causing a little stir – and the final chapters felt numb, as if the situation of the characters was always going to be like this from the first moment to the last. And again, it felt hard to impregnate the characters, Santiago somehow seeming detached from his life as a political prisoner (Benedetti failed to bring his isolation to life in ways that many other novelists have) and many passages, especially those from their daughter Beatriz (who seemed far too knowing and calculated to actually be a young girl) adding little in dramatic tension or narrative development. Okay, so the last of these is not really what the novel is about, but ultimately there has to be something that drives you to the end of the book and here I felt Benedetti failed.

Now, there may be reasons for this. The translation could have lost some of the original’s charms. Perhaps, my expectations were too high, expecting something that was never possible. But ultimately, no matter how many ways I try to spin it, I can’t get away from the fact that these two books left me wanting more. They both showed Benedetti as an inventive storyteller with some fine turns of phrasing, but they felt insular, their characters tied to the pages, rarely offering anything other than a pencil drawing of what their lives were like.

Springtime In A Broken Mirror and Who Among Us? are released by Penguin Modern Classics

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.