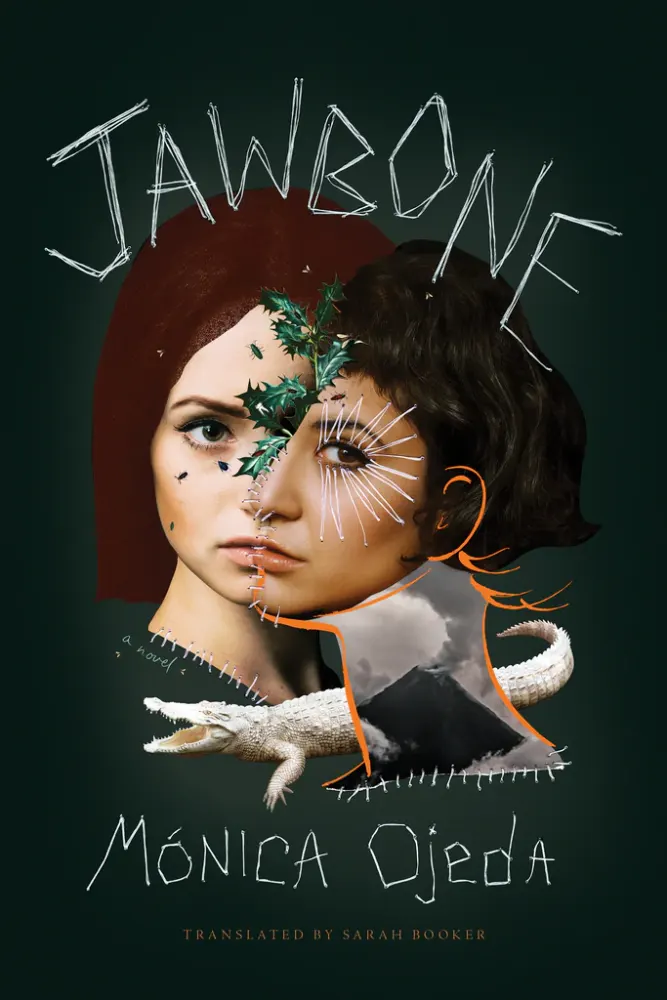

Mónica Ojeda’s ‘Jawbone’: The Outrageous, Dangerous and Disgusting World of Girls Grappling with Suppression

12 April, 2022If Freud had a sister that was writing about the security of young girls in Ecuador, perhaps that piece might have turned out close to Jawbone. Or alternatively, perhaps this book is like the setting of Lord of the Flies, if you chuck in some twisted Latin American horror and make all of the characters female. It’s very hard to describe Jawbone because it is essentially in its own category of fiction, and the world it creates and explores is one where young girls gather together to perform outrageous, dangerous and disgusting activities. It is dark and gruesome but in a quietly menacing way. It won’t be everyone’s cup of tea. But it certainly pushes boundaries and there is a huge amount to unpack, though it could probably do with quite a few trigger warnings.

The main premise of Jawbone surrounds a group of schoolgirls in Ecuador, around fifteen years old, where we see what they get up to and what they imagine when they are unleashed from the suppressive setting that they, for the most part of their lives, grow up in. The girls – the predominant focus being the leaders of a group of five named Anneliese and Fernanda – ordinarily live in gated compounds, at school they are strictly controlled, and there are multiple other threads of the story that deal with brutally crushing pressure from mothers. We see shocking contrast to these high levels of control and suppression, that the girls gather in an abandoned building which “quickly became their anti-parent, anti-teacher, anti-nanny headquarters, a space of phantasmal sounds that felt both gloomy and romantic.”

What the girls do get up to there, their “clumsy experiments destined not to catch on but that forged a path to a coordinated inquiry that tried to stretch the limits of what they could do to themselves in a place without adults and without rules” is probably the part where it starts to get a little weird, twisted and Lord-of-the-Flies-like. What Anneliese and Fernanda get up to on their own (and for most of the book they are inseparable and intimately close to each other) is where things get graphically and viscerally disturbing, psychologically confusing and very gruesome. But then again, books have won Booker prizes while being much more uncomfortable. It is just worth pointing out that Jawbone goes beyond just violent, it isn’t too surprising to see critics using words such as “unsettling” or “creepy”. But it is also about that fine and very blurred line, a paradoxical set-up where the girls are both victims and perpetrators, where they are terrorising and terrorised and where they fear themselves as much as they do anybody else or anything else.

The ‘main characters’ are probably Anneliese and Fernanda, as well as their teacher Miss Clara. Miss Clara is a whole separate strand of weird and shocking (and in keeping with the others, she is also both a victim and perpetrator of violence) through an interesting concept where she feels so guilty about the death of her mother that she imitates every facet of her character and habits by wearing her clothes and adopting her speech mannerisms, even though she simultaneously has not worked through the very complex and difficult relationship with her mother in her own head. Miss Clara’s internal monologue is one we hear frequently, and it is extremely confused and quite disconcerting. I will admit I found her character quite hard to get my head around as I am not sure whether we are supposed to sympathise with a teacher who not only breaks her duty of care to her students quite ferociously but clearly has a concerning capacity for violence.

Of the main characters, we have the least insight into Annaliese’s mind and feelings – unlike Fernanda and Clara where we have access to their internal thoughts, we generally only see the side of her that she projects outward. But she projects a huge amount and this opens up a real display of imagination. She tells countless stories of her creation, the “White God” (there is a very interesting discussion around the imagery connected to this in the translator’s note) and Anneliese publicly performs her creations through “creepypastas”, i.e. by posting them to forums online (there is also insightful commentary around the linguistic concepts behind this in the translator’s note). So when we see her openly talking about her creations, perhaps a combination between her self-disgust and fear of puberty together with an amplified tendency to gore, we see her going through the process of performing the stories to the girls in person and to those beyond the smokescreen of her online persona. We don’t quite know the emotions she has or attaches to her stories, but safe to say we can assume these emotions are quite complicated.

The closest to Anneliese’s internal monologue we get is when she writes a long letter in the middle of the book that includes some insight into her viscerally graphic imagination, and also the treatment she received from her mother. She discusses for instance how her mother told her stories in the bath, stories that started with “you won’t believe what happened to one little girl because she talked to a stranger” or “because she disobeyed her mom and left the house alone” or “because she didn’t know how to say no” (Anneliese notes, “in the stories it is always the girl’s fault”). I have personally actually always been a bit torn on this point. On the one hand, in line with Annaliese’s point, the burden shouldn’t be on the girl and actually it is also patronising – my mother very much likes to insinuate this to me and my sisters too – to assume that horrible things happen to girls because they weren’t careful enough. On the other hand, terrible things do happen to girls, perpetrated by those who take advantage of their vulnerability and sadly there is a reason to worry.

Jawbone is a very intricate and multi-layered book, written in a verbose and linguistically-rich style, I have no doubt it would have been extremely challenging to translate, and that exercise has been admirably done by Sarah Booker. Jawbone is also deeply steeped with imagery. My personal favourite example is where, in recollecting a comment made by her mother that Ecuador is a country with a significant number of volcanoes, Miss Clara also notes that volcanoes are beautiful but with the “potential to annihilate”. Even more than that, volcanoes “insinuate their own destruction”. With this level of creativity stacking up on every page, there is a lot to digest from Jawbone (this last pun is mine, is not intended, and it is nowhere near as sophisticated as those in the book).

Mónica Ojeda was born in Ecuador in 1988. She was included on the Bógota39 list of the best thirty-nine Latin American writers under forty, and in 2019, she received the Prince Clause Next Generation Award in honour of her outstanding literary achievements. Translator Sarah Booker is a doctoral candidate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with a focus on contemporary Latin American narrative and translation studies.

Jawbone is published by Coffee House Press, a non-profit publisher of literary fiction, essays, poetry and other works that don’t fit neatly into genre categories. You can buy the book from Amazon (UK | US) and Bookshop (US).

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.