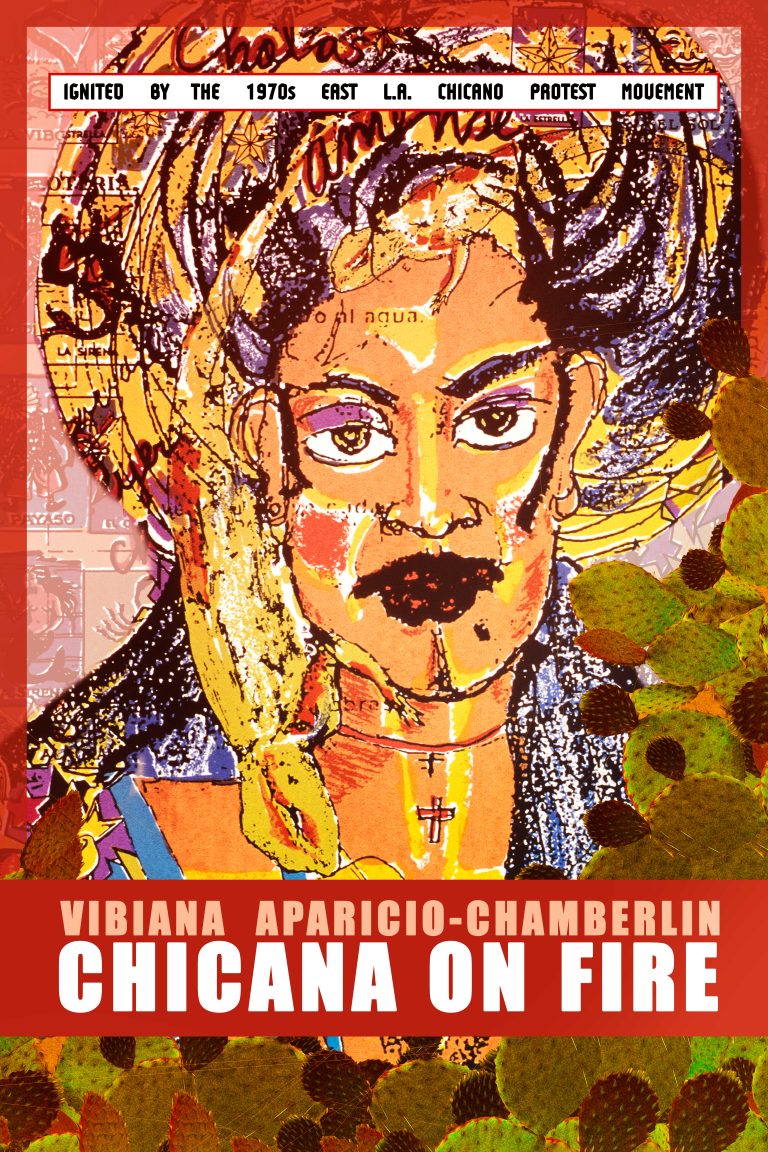

Poetry, Politics and Prickly Pears: A Review of Vibiana Aparicio-Chamberlin’s ‘Chicana on Fire’

14 December, 2022Vibiana Aparicio-Chamberlin‘s poetry in Chicana on Fire (2022) is testimonial and collective. Born and raised in Boyle Heights, California, she holds an MA in Theatre Arts and Educational Administration from California State University in Los Angeles. She is an activist, a writer and a visual and performance artist. Aparicio-Chamberlin has been published in several literary and art magazines. In her preface to Chicana on Fire, she describes her childhood memory “as a need to shout out her grievances, for this I was called a bad mouth, a grosera. By today’s standards I would have been considered a critical thinker.”

Aparicio-Chamberlin’s poetry draws us into the centre of her inner glow. To open her book is to encounter an aroma of wet earth. History and politics are braided into her poems and stories. At times, her poetry and storytelling processes are of volcanic dimensions; eruptive and explosive. On other occasions, they are soft swells of tender maternal care, dedicated to her family and loved ones.

Her feminist consciousness recognises that women’s liberation depends, in turn, on the liberation of men from their own dominant patriarchal chains. Aparicio-Chamberlin’s specific branch of feminism draws a clear distinction between white (liberal) feminists and that of her Chicana identity in which family, community and her Mexican heritage are all interconnected by her Indigenous roots and its mythology. Her writing is the offspring of a cactus tree with arched arms full of prickly pears, a symbol of resistance against droughts of love and the intolerable heat of racism.

Aparicio-Chamberlin’s identity and cultural references weave throughout the book like a huipil. Each page of Chicana on Fire opens with a grito of reflection or a call for redemption. Unlike academics who, in their attempts to be politically correct, describe the earth as a biosphere, Aparicio-Chamberlin employs her distinct oppositional thinking to unite the majority of the world’s Indigenous populations who refer to our planet as Mother Earth; a giver of life. The chapters titled “Cactus Flower”, “Prickly Pear”, “Thorns” and “Nopal” are in communion with Aparicio-Chamberlin’s passion, feelings and emotions. She amplifies her strength in these chapters with teyolia, the spiritual force that resides in the human heart. An intimate love experience described “Flor y Canto” feels like a heart struck by a cactus thorn; the more you attempt to remove the spine, the more the wound hurts. A fragment of this poem reads:

“With insatiable hunger you stroked my waist.

Now you turn your eyes away from me.”

“Flor y Canto” without a doubt speaks truth, “Every time you refuse tenderness, your heart dies — Loveless, unrequited.”

In “Don’t Open the Door”, Aparicio-Chamberlin brings us close to the harrowing drama of an undocumented family. The poem starts as a letter from a teacher to Alejandro’s mother warning her to tell her son not to open the door, to keep quiet and to stay still if he hears anyone knocking. The mother’s consecutive instructions of don’t do this and don’t do that to her son string up like the beads on a rosary, one right after another.

The 1970 sheriff assault on a peaceful Chicano march against the Vietnam War at Laguna Park in east Los Angeles led to Aparicio-Chamberlin’s poetry of protest. Her indignation sparked inspiration for a series of poems addressing police brutality. In “Attacked, Tear Gassed, And Bludgeoned By Sheriffs At The National Chicano Moratorium Against The War In Vietnam East Los Angeles, August 29, 1970”, Aparicio-Chamberlin reveals her outrage and determination to never forget the life-changing incident. She writes, “I froze; lost my speech. I cried inside my head”, with her invisible tears fossilising like amber in this poem.

Aparicio-Chamberlin’s poems and stories capture that which, at times, other art forms cannot; the breath of sound united with words that rhyme out the soul of her experiences. Her poems are a lyrical documentation of life.

For Kenyan writer and scholar Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o “content is ultimately the arbiter of form”. The content in Chicana on Fire relampaguea, flashes like lightning, as in Pablo Neruda’s Canto General; a Latin American continental protest anthology. Aparicio-Chamberlin’s content departs from her commitment to rescue and preserve memory in a way that provides her community with the necessary space to evaluate its role as an actor in the writing of its own history.

Palestine, Haiti, Vietnam and, as such, the Global South as a whole also form part of her political poetry. In “Oh, Palestine”, Aparicio-Chamberlin wishes to build a perfumed bridge in order to be closer to her Palestinian sisters-in-struggle. In her poem dedicated to Haiti, she describes her desire for a small plot of land for the poor and her hope for “No more quaking only the Earth stretching and scratching to loosen the soil for beans and corn to grow for you.”

In Aparicio-Chamberlin’s short story “The Bishop’s Ring”, a vendor catches sight of the eponymous bishop in front of the Los Angeles Cathedral on Grand and Temple. She rushes across the street and presents the bishop with a handmade clay rosary as a gift. The bishop ignores the gift proffered and instead puts out his “manicured hand”, adorned with a ring, to be kissed by the vendor. She hesitates and lightly touches the bishop’s ring with her lips, yet he moves away without a blessing or a kind gesture for this hardworking woman. Aparicio-Chamberlin’s keen sensitivity captures contradictions in the making. Class consciousness is layered within many of her stories and poems. She is vivid in her descriptions of the vendor and shrewd with her observations on the relationships between those who hold power, which is often accompanied by arrogance, and those positioned below; the working class.

Chicana on Fire reignites the 1970s’ internationalist solidarity with the Third World. Space, place and geography are continuously interwoven in this work. In “We Didn’t Cross The Border, The Border Crossed Us”, Aparicio-Chamberlin traces the constant growth of a border scar that has been exacerbated by US imperial ambitions and the oppressive (racist) border measures promoted by ex-presidents, James Polk, Bush, Clinton, Trump and Obama towards Mexico and Latin America. In this poem, Aparicio-Chamberlin reminds the reader of the impact that steel walls with razor ribbons have on wildlife on both sides of the border.

German philosopher Herbert Marcusse’s (1898-1979) concept of the ‘Great Refusal’ forms the backbone of Chicana on Fire. Marcusse’s central idea revolves around a refusal to accept life as it is without question. Aparicio-Chamberlin rejects alienating doctrines that justify the exploitation of human beings by others all over the world.

This series of stories and poems is written with fire and courage. Aparicio-Chamberlin brings forth a ballad of cantos dedicated to love and intent on promoting discussion. Chicana on Fire is sustained by the ganas, the will, to build a different and promising world for all.

Chicana on Fire is available from Amazon

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.