Victor Garcia’s Yo Soy (I Am): An Act of Visual Rebellion

08 October, 2018Perspectives: “Yo Soy American”, an art exhibition at the Jean Deleage Art Gallery in the Casa0101 Theater in Boyle Heights, presents the debut of eight emerging young artists with an inter-visual conversation with visitors, communities and amongst themselves. Traditional color and black and white photography, paintings, along with image transfers onto wood panels that have been merged with experimental processes, unveil a receptive conversation between technique, method and content. Perspectives attempts to unfold the revolving door approach to past and current historical patterns of exclusion.

The salon discussions that were mediated by East Los Angeles College photography professor Mei Valenzuela with the participating artists were a prelude exploration of ideas and assumptions of what shapes opinions and perceptions of reality for this exhibition. The thematic behind Perceptions took into consideration issues of identity, current political circumstances, adaptability to new environments, cultural imperial definitions of others, examination of western anthropological biases, the self-realization of class consciousness and cultural markers as points of inspiration.

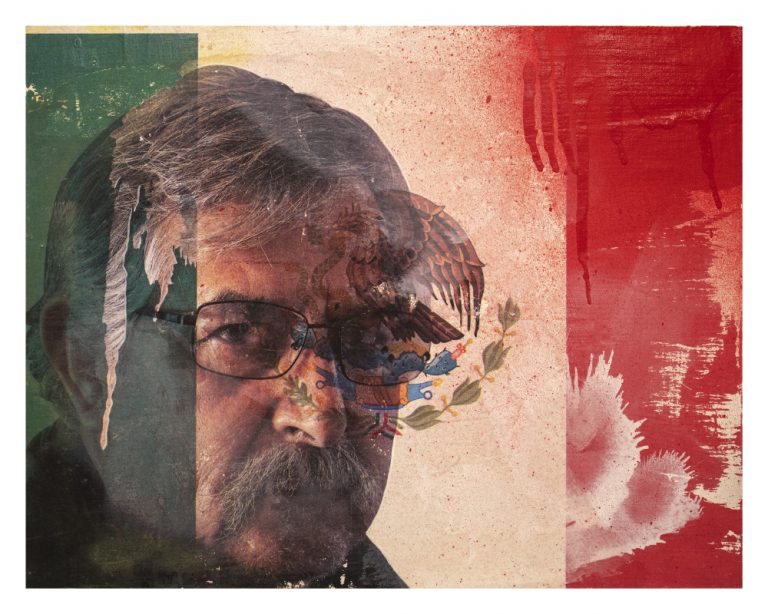

Victor Garcia was one of the artists to be featured in the exhibition, presenting a series called “Yo Soy American” (I Am American) that consists of image transfers onto nine wood panels. His exhibiting work is “an exploration of feelings and emotions of being a citizen of a country that doesn’t really want you.” Of Mexican descent himself his expressive work is a process of brushed panels with red, blue and green paint layered with multiple images that makes reference to the U.S. and Mexico. The aerosol adds another dimension to his work. In the study of graphology, the over spray of aerosol dots and lines dripping across the series become points of hesitation. Garcia metaphorically relates drops and smears as uncertainties when confronting questions of identity for people of color. For one guest at opening night, the dripping dots of paint were stains that could not be removed or bleached away, they are permanent. Does her observation allude to a discomfort brought about by the presence of Latin@s in the United States as a stain? Could that help explain the historical regressive policies of deportation, expatriation, operation wetback, the derogative literature against Mexicans, immigrants and Mexican Americans or the current xenophobic belief of making America great again, means without them (people of color)?

Garcia’s series duels against the imposition of racism as an intoxicating paradigm in defining who is and what makes one an American. Is racism a reaction of fear, dis-empowerment or the arrogance of power? By exposing paradigms of exclusion, his artwork draws on the limitations of how racialization is approached not excluding Latin@s, Chican@s and Mexican Americans who search for solutions through a western lens. After all racial classifications and the construction of the other as subjects (non-Euro) began with colonization. Instead he seeks to widen the aperture and allow the entry of more light to contest discriminating practices.

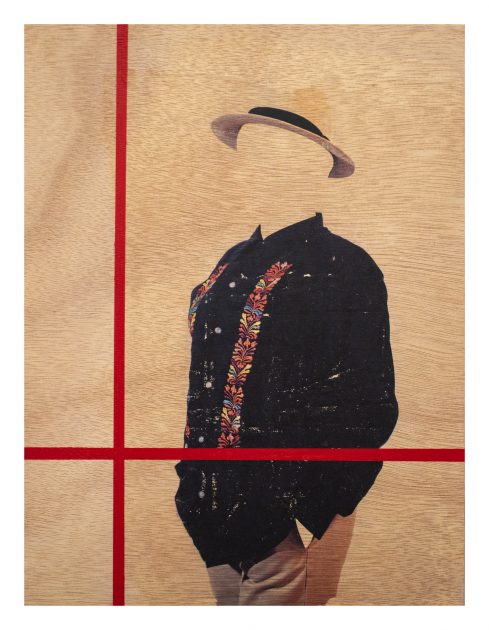

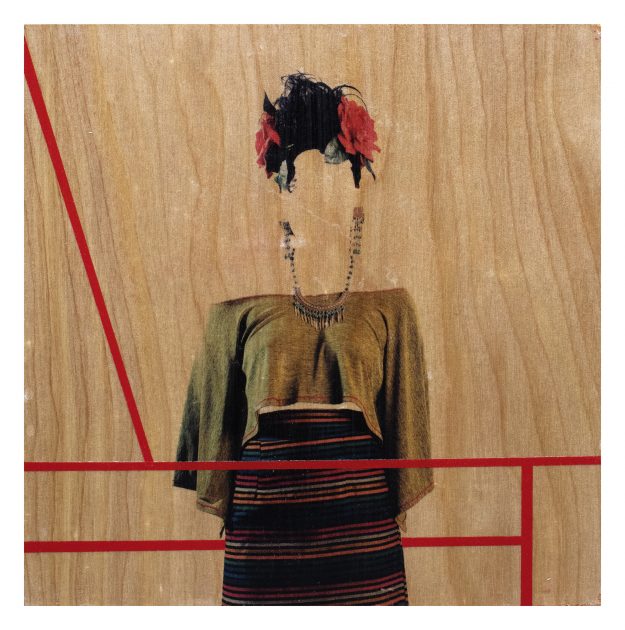

Four exhibiting wood panels with faceless full body portraits of people combinedly dressed between indigenous and contemporary clothing map an affirmation of duality via the language of clothing. Two of those portraits, with thin red lines around the edge of the frame, mark a binary contradiction between who is visible and who is not. In Beyond Abyssal Thinking philosopher Boaventura de Sousa Santos points to such contradictions as unnatural developments against differences justified by western modern law and modern knowledge. Can the faceless also suggest the approximately twelve to fifteen million people whose ‘Legal’ status in the U.S is detained in an ambiguous perpetual state of invisibility?

Although not directly emphasized, the red vertical and horizonal lines also remind one of the once-upon-a-time of mapped areas of the city of Los Angeles, redlined to systematically deny specific non-white groups from purchasing homes, property or obtain services. According to a recent article in the Washington Post, despite the ban on discrimination 50 years ago neighborhoods that were redlined continue to struggle economically today.

Garcia’s bilingual title “Yo Soy American” for this series counters the hegemonic categorization ‘Hispanic’ that came about during the Reagan era to assimilate and coral Spanish and non-Spanish speaking Latin@s under one label. Instead he amplifies and discovers multiple ways of being Latin@, Chican@ and Mexican American that does not take away from them being a person and an American. This whitewashing definition, ‘Hispanic’, is emphasized in his work with strokes of white paint as a backdrop superimposed with portraits of family members allowing aspects of his cultural mexicanidad to permeate. He breaks the encirclement of stereotypes by allowing Mexican American history to count itself in as a contributor in the making of the United States and the role it has played as an advocate of social justice. His presentation is an “act of visual rebellion” defrosting histories buried beneath tons of I.C.E with a skilled technical method that transmits his reflective intellect and sense of dignity.

Balancing in and out of his identity, Garcia puts forth what racism entails: the conversion of others as inferior and the impediment of an unbiased and unprejudiced conviviality in a diverse environment. The devaluing of cultural particularities, the suppressing of confidence and self-esteem in people of color effect healthy constructive means to navigate in any society. Such an impediment derails an assurance of being equal and “not be judge[d] by the the color of one’s skin, but by the content of one’s character” (to quote Martin Luther King Jr.).

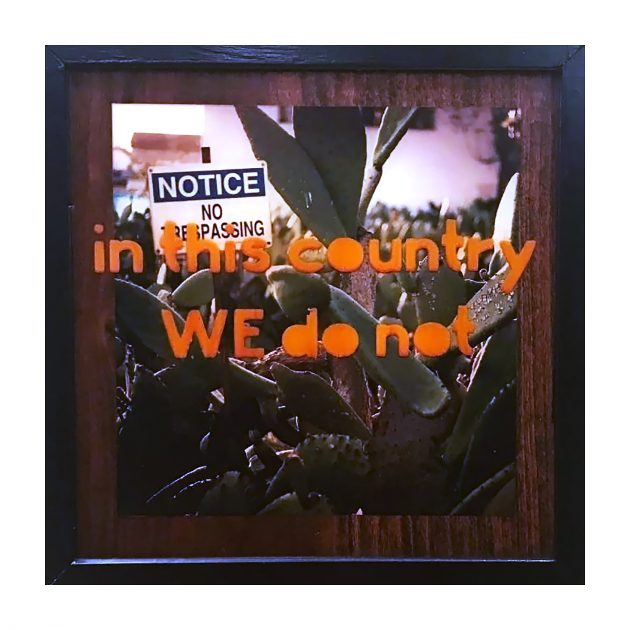

In a piece titled “Face the Fallacy” [pictured above] Garcia has an image of a cactus tree overlaid by text that reads “In this country we do not….” It’s a phrase that he heard when he accidentally blocked an intersection with his vehicle only for a white male roll down his window and direct himself to Garcia with those words, “In this country we do not….” The incomplete text stuns after a few rereads. It is then when the force of such composition of discomfort and bias in those words hits home. The immortalization of a racist reaction as an art piece to this incident serves as a reminder that embedded racial profiling based on the color of one’s skin is still prevalent in society today. It recalls a warning by African American intellectual W.E.B Du Bois who stated in 1903, “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of color line.”

The questions posed in Garcia’s work are: “What are the building blocks of perception that justify and rationalize white(ness) superiority over others?”; “Is racism the continuation of a provincial Eurocentric method of codifying between civil (Euro) and uncivil (non-European) an extension of colonization?”; “How did the provincial Eurocentric local and regional belief of superiority (higher civilization) become a natural… universal (global)… racialized… social classification and ‘not a consequence of a history of power’ an argument examined by sociologist Anibal Quijano in his extraordinary essay “Power, Eurocentrism and Latin America”?”

A more humorous and positive note to “In this country we do not…” is the reason for the cactus, which Garcia expands on as being a deep pre-Columbian symbol for Mexican culture by adding, “Guess what? Nopales (cactus) do grow here and we do eat them too!”

Garcia’s work is reflective as it denounces. His series is a response to not cease the conversations that can quilt healthy multiple ways of coexisting together.

Perspective can be viewed until October 25, 2018. For more information please visit www.casa0101.org or email [email protected]

This essay is dedicated to sociologist Anibal Quijano, 1928 – May 31, 2018

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.