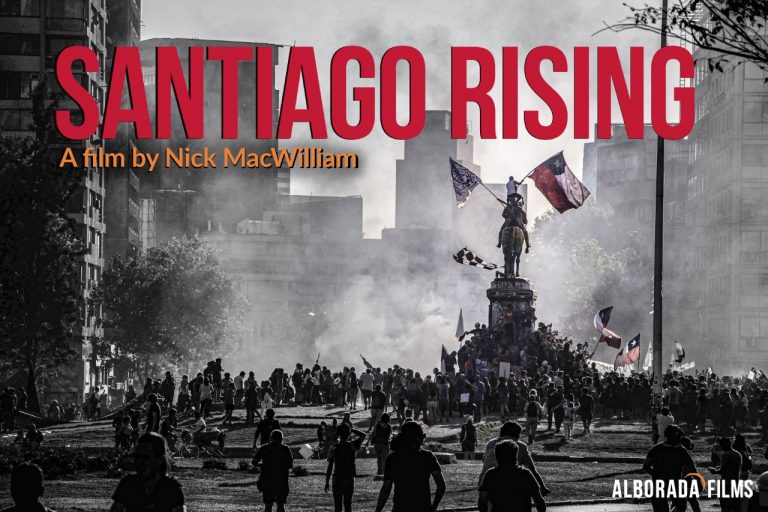

Chile’s Social Uprising: An Interview with Nick MacWiliam, Director of ‘Santiago Rising’

20 February, 2021The documentary Santiago Rising (2021, dir. Nick MacWilliam) looks at recent protests in Santiago de Chile and the government response that sent shockwaves across the world. What started as a student demonstration against a hike in metro fares in 2019 spread to wider protests against the social and economic inequality in the country. An early adopter of neo-liberalism under the rule of General Pinochet (1973 – 1990), Chile went through a mass privatisation programme of everything from education to pensions. More than thirty years since the return to democracy, the country still lives under the same 1980 Constitution and unequal economic model.

MacWilliam weaves together different scenes from the streets of Chile’s capital during the 2019 protests: colourful demonstrations full of music, banners and singing. There are impromptu concerts, political debates and an army of cyclists who take to the streets in solidarity. The difference between the peaceful demonstrations and the tactics of intimidation from troops and tanks couldn’t be more powerful. The government response is shocking to watch. Protesters and bystanders are attacked with water cannons and rubber bullets. MacWilliam captures the turn in mood, lingering to talk with peaceful protesters caught up in the teargas or water jets, and there are more than a couple of moments where he himself is in danger while trying to capture what’s happening.

This is a film as much about resilience and solidarity than anything else. We discover a whole network of community assemblies, pop-up concerts with artists such as Ana Tijoux, and radio stations covering the demonstrations. MacWilliam connects these movements to the long-standing tradition of protest music and art in Chile – the songs of Victor Jara ring out as people demand their right to meet peacefully in public squares: a simple act now under threat from the tanks and truncheons.

People’s willingness to talk to the camera show us how widespread the issues are but also how diverse the participants are. It also shows us how desperate people are to show their story, one that has been ignored largely by the mainstream Chilean media. The repression of peaceful protests and the labelling of protesters as internal enemies have provided a one-sided and distorted view of events in Santiago. This film serves as an important social document on the social transformations taking place in Chile.

Ultimately, Santiago Rising is a film about a reawakening of a Chilean consciousness, and of a society that is raising its voice. The energy and the resilience of the protesters is inspiring to watch.

Sounds and Colours caught up with Nick MacWilliam, director of Santiago Rising, to find out more about the documentary.

Where did the idea for Santiago Rising come from?

I’d lived in Chile from 2010 – 2014; I knew a bit about the history of the country before but I wasn’t entirely expecting the legacy of the dictatorship to be so prevalent in daily life. Obviously, there’s the whole economic model, an extremely free market social system where pretty much everything is privately run and geared towards profit. But then there was the other side of the coin: the repressive state apparatus which maintained it all in place. There were big social mobilisations in Chile, big protests against these forms of inequality. In 2011 there was the student movement, which was huge. This was the first generation born after the dictatorship; they didn’t have the fear of the dictatorship but they had this anger at the inequality and injustice. But every time there was a protest there was this extremely authoritarian state response. That gave me an idea of the opposition that existed in Chile to the system, and it was during that period I could see how repressive the state could get.

Being in Chile for four years, this seemed to be a permanent state of affairs between this hard-line economic model and this hard-line policing model and that people were being more and more squeezed, the cost of living was getting higher. I left in 2014 and I was very aware of the social tensions there.

In 2019, Chile had this social explosion. I already had a trip planned to Chile for the first time in five years; once I knew I was going to be there I took my camera. I couldn’t miss this and [I had to] be part of it, in the streets and see the incredible unity that existed between people and the cultural expression which I knew would be there because of my experience of Chilean protests. There was just so much happening; it was almost as if I was being led, anywhere I went with the camera there was stuff happening, and people were supportive.

It’s interesting to see the breadth of protesters; there’s quite a lot of diversity of voices represented in the documentary.

It was one of the things I was keen to show. I think people came from different political backgrounds. You obviously have the feminist movement, the Mapuche movement, the student movement… But there were a lot of people who hadn’t been on many protests before and were now going on them. People had been so incensed by the government response to the protests: [It started with] people jumping metro gates, getting heavily beaten up by armed police. That triggered something in people, and [Chilean President] Piñera’s response to that was to implement a state of emergency, which put the military on the streets for the first time since the coup, in a country where under there’s still going to be a lot of trauma because [the dictatorship] never really been properly addressed. There’s been so much impunity and human rights abuses are still continuing today. All of this had this huge catalysing effect, in what is now the Plaza de la Dignidad, over a million people met in the square in protest.

How did people react to you filming?

Not everyone was happy: you’re a foreigner, there’s an oppressive situation going on, but the vast majority of people were supportive when I explained to them. I know the area, I know the place and the culture. I speak kind of Chilean Spanish so that helped me connect with people. I knew about the political context so I was able to relate to people easily. The vast majority of people really wanted people in other parts of the world to see what’s happening in Chile, to see what the government is doing. So, it went from there. What you see in the film was a result of that. Protests in Chile are action-packed and veer from inspiring and beautiful to horrific and brutal, and I was in the middle of it with my camera.

There’s quite a tradition of storytelling, Gabriel Mistral, Pablo Neruda, in the music dealing with social and political issues, there’s street art. I think Chile has a very strong oral tradition, people enjoy speaking and have something to say. I think it lends itself to a film like this, where you’re basing your film in the voices of the people on the streets. Everybody wanted to get their story documented for posterity.

What about the role of the media in protests like this?

I didn’t see any big news reporters at hardly any point. On the protests I don’t recall ever seeing them. Telesur was one of the only major news organisations that were there on the ground and that was portraying things in a balanced and fair way; they were showing the state abuses, they were showing the repression.

The independent media scene, like Señal 3 [a Community Television station in La Victoria, Santiago], like Radio Villa Francia, Primera Línea Prensa – there are so many of them – also covered everything, and most of their footage is just coming from mobile phones. Their following is massive. They were archiving all the material online so people could refer to it. There was so much material, the sheer amount of videos, things were happening so fast.

What would you like Santiago Rising to achieve? What impact would you like it to have?

I didn’t necessarily make the film for one core audience, but I did make it so anyone who watches it can understand Chile without having any prior knowledge. Which is why the first part of the film is fast paced, to show who the social movements were and the background of the dictatorship. It was important for me that anyone could watch the film.

For the Chileans, I learnt so much from watching Chilean political cinema. And while I think a lot of the stuff in the film is what people there will know, I think in terms of memory [of the protests], this [documentary] creates an historical document of what happened. But one that also says to Chileans, we admire what you do. So many people around the world should see what you’re doing. You have a brutal economic system that was put in place through the murder and disappearance and torture of thousands of people, and that’s a system that goes on today. And you’re fighting back with musical instruments and bicycles, and you’re fighting back with your voices. It’s inspiring. And, you’re getting results from doing that. I want to show Chileans we admire you for that, but I also want us to take lessons from that.

Santiago Rising is available now to stream/download on Vimeo.

Click here for ‘Chile’s Social Uprising: A Year in Photos’.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.