Dueto Dos Rosas Are Defying The Mainstream With Their Ranchera Roots

03 June, 2022California-based Dueto Dos Rosas are composed of Indigenous Mexican-American sisters Emily and Sheyla Rosas. They began uploading videos to YouTube in 2014 of their traditional-style performances of rancheras and corridos, and by 2017 some of their videos were receiving millions of views. Beginning in 2019 the sisters started releasing their tracks on streaming music platforms. Their popularity has been earned independently, without corporate sponsorships and the powerful mechanisms of market saturation in the hands of the typical (US-based) tastemakers of Mexican popular music. Their attraction is based in the profound desire throughout Mexico and beyond for a return to folk roots.

While many of the songs they sing became staples in Mexico and abroad, their manner of returning to the simplicity and sincerity of Lucha Reyes and the duets of the 50s and 60s stands in stark contrast to the trends pushed out since those days. Returning to the post-Revolutionary roots of ranchera, when evocations of the past were utilized to construct a new national identity based on the lives of working people, Dueto Dos Rosas cut through the fog to bring vernacular music back to the pueblo. That means freeing it of external interference, such as the industry categorization of “Regional Mexican” created to serve US radio formats, and processes of drearily crass “modernizations” such as grupera.

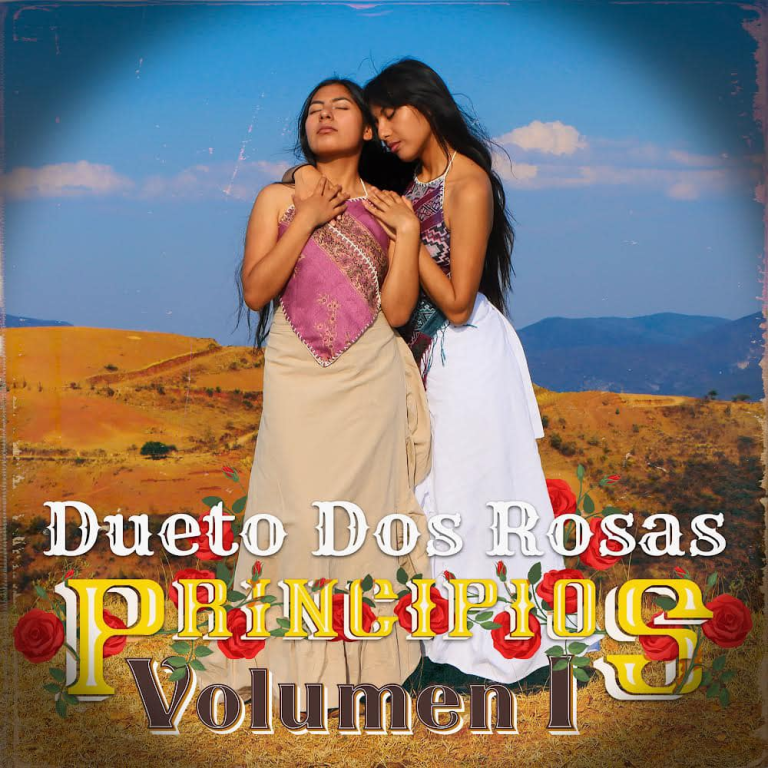

Their second album-length release, Principios Vol. 1, continues their custom of digging through the crates to bring back words and sounds from the first half of the last century. There are numbers popularized by duos Dueto Las Palomas (“Ojitos Claritos Chinitos”) and Dueto América (“La Vida Infausta”). These are also numbers representative of the earliest roots of ranchera. The first track of the album, “Gaviota Traidora”, was penned by Margarito Estrada Espinosa, a peasant migrant from Querétaro who found success in the waning years of the Golden Age of Mexican cinema writing rancheras for Chelo Silva and Flor Silvestre. This would later put him into direct contact with acts such as Dueto América, Las Jilguerillas, and Dueto Las Palomas, feeding multiple generations hungry for stories of country life and hardship which could resonate across Latin America.

The third track on the album, “La Vida Infausta”, was written in the earliest days of the ranchera, by Samuel Lozano from Cuernavaca, a man who faced political persecution during the Mexican Revolution for songs such as “Corrido Antirreeleccionista” and “La Muerte de Madero”, which he sang on the streets of the capital. It is said that Pancho Villa gave Lozano a guitar when the singer joined his forces in the north. We can also speculate on even older roots in track five, “El Novillo Despuntado”. It has variously been interpreted by Las Jilguerillas, Los Hermanos Zaiar, Luis Perez Meza, and others. Its composition is normally credited to Ernesto Rubio, and his brother José recorded it for Columbia in 1927 as part of the duo Rubio y Martinez. Yet this playful song loosely about a steer with tipped horns has a lyrical theme with many iterations found elsewhere. In fact, there is documentation of a 1929 performance by Alejandro Manzo of a song by the same name, as well as credits given to songwriter and folklorist Alfonso Esparza Oteo and composer Ignacio “Tata Nacho” Fernández Esperón. To be sure, the Rosas’ version, credited to Rubio, retains the disjointed quality of a folk song composed of floating verse. There is certainly the tantalizing possibility of some voices singing to us here beyond the mists of recorded history, speaking to us about gambling and preferring a light horse to a beautiful wife.

The fourth track on Principios is of particular interest, for it shows the expansiveness of the Rosas’ vision when looking at Mexico’s musical traditions. Before there was the post-Revolutionary national formula known as ranchera there were diverse regional sones. With accompaniment on jarana and violin, the sisters’ version of “El Corrido de Chihuahua” brings to life the lyrical imagery of sotól liquor, cattle, and mining in a sound that is both norteño and something more ancient. We hear, in particular, the kind of fiddle playing which can still be heard throughout the Sierra Madre Occidental, including in indigenous Mayo communities in Chihuahua. It is a kind of fiddling that comes with relative tunings and controlled dissonance, the companion to traditions of handmade cousins to the violin such as the Wixárika/Huichol xaweri. It recalls at once the sound of the earliest vernacular fiddlers to ever be recorded, such as Fiddlin’ John Carson, and is evidenced in Indigenous fiddle-playing throughout the Americas as showcased in Smithsonian Folkways 1997 Wood That Sings compilation. The Rosas natural, anti-glossy charm is here put to use in recovering the regional diversity that so-called “Regional Mexican” corporate mechanisms have all but glossed over. There is much more potential for them to explore in that direction.

In many ways, as Mexican music goes, so goes Latin America. This is especially true when the gravity of the US-based music industry is part of the equation. As much as rancheras have been domesticated in Chile, so has the Colombian duo Las Hermanitas Calle’s version of Margarito Estrada’s “Gaviota Traidora” left the Mexican-ness of the lament for a treacherous seagull behind. Radio stations in far-flung corners of South America would come to play such rancheras meant to construct a revolutionary national identity for Mexico in programming labelled “country hour” and the like. Estrada wrote “Gaviota Traidora” for Flor Silvestre to record in 1964, and the force of successes like it would help elevate Silvestre and her husband Antonio Aguilar to the status of superstars, and the progenitors of a dynasty that has dominated airwaves and related media across Latin America for three generations. They owe everything, of course, to the original voice. If we were to recall the immortal words of Emiliano Zapata, that “the land belongs to those who work it with their hands,” we may begin to ask, “to whom do these rancheras belong?”

There is actually a poignant comparison readily available between the Rosas and the Aguilares. The Rosas’ father, a hardworking immigrant from Oaxaca, has long been at their side. For her part, born-millionaire and heiress to the family empire, Ángela Aguilar, has said, “Because of my dad, I’ve been able to perform in huge venues all over the world.” Ángela’s cousin, Majo, also recently recorded her own version of the song that Estrada wrote for her grandmother. In another illustrative contrast, the video for “Gaviota Traidora” had accumulated around 1.3 million views within six months of being uploaded in December 2021, while Dueto Dos Rosas video “Carta Jugada”, uploaded in the same month, accumulated over 1 million… all despite Aguilar’s benefit of having been featured since then in all the institutional news outlets to which being signed to Universal and ranking #1 on a Billboard airplay chart give you de facto access. Aguilar’s version attempts a kind of traditionality and simplicity, but it lacks sincerity and fails to convince. The fate of the Aguilar family is to be tied to the momentum of ever-increasing commercial spectacle and sensationalism. If that momentum – and the wealth and privilege that they’ve accumulated through it – were all to suddenly disappear, would anyone pay them any more attention? We cannot doubt, however, the persistence of Margarito Estrada’s composition.

There are two other tracks on Principios that are notable for showing the sisters’ expansive breadth as “El Corrido de Chihuahua” does. These other songs show that expansiveness in different dimensions, however. First of all, there is their cover of “El Otro México”, originally recorded by Los Tigres del Norte. That Los Angeles-based group’s 1974 recording of “Contrabando y Traición” is often regarded as the birth of the narcocorrido, although they have always rejected that label themselves, holding that any corrido about smuggling was simply yet another corrido about the unglamorous realities of Mexican life. As a result of such songs, debates were ignited in Mexico surrounding the canonization of narcocorridos within school texts on folk culture, revealing a deep divide in Mexican society. It is such a divide which Los Tigres’ “El Otro México” (“The Other Mexico”) ruminates on:

“While the rich go abroad to hide their money

“El Otro México”

and to travel around Europe

We Mexicans who come wet [i.e. enter the US illegally]

send almost everything back to those who stay behind […]

Because a cacique [wealthy land owner] who leaves lands and cattle

to cross the Rio Grande – that is something you’ll never see!”

By using their voices to speak on behalf of the “other Mexico” of workers, peasants, and migrants, Dueto Dos Rosas have affirmed that their musical project has a socially conscious dimension. Other songs in their repertoire show this, as well, such as “El Albañil” (“The Construction Worker”), featured on their YouTube channel but as of yet unreleased on streaming services.

The final track on Principios illustrates this social consciousness even more. It is a cover of The Louvin Brothers’ “When I Stop Dreamin”, and it is the Rosas’ first recording in their “second native language”, English. In their YouTube video description for the cover, they state that they identify with the song because it is also country music, just like ranchera. Their version is undeniably beautiful, and even country fans who know the Alabama brothers’ original will surely admit that there is something majestic in the adaptation. The voices are powerful and clean like the Mexican duos of yore, but there is nothing lost of the deep-fried Baptist sincerity of the original. What we have is the “other Mexico” recognizing itself within this “other United States”. It is a priceless invitation extended across linguistic and cultural barriers.

With current retro trends in independent country/folk music in the US from figures like Charlie Crockett, Leyla McCalla and Willie Watson (and the curious surge during the last decade in interest in the traditional cross-border tune “Hills of Mexico”), it seems like it ought to be only a matter of time before we see these two worlds combine in a more substantial way. The internet has proven a powerful tool for connecting the sisters to an eager fanbase throughout Latin America. That that fanbase will identify their music with their own “other” side of Latin America, apart from the enshrined celebrities and monied interests which continue to oversaturate markets and shape popular culture, is hopeful. Even more hopeful is the prospect that many more people from the “other” side of the tracks beyond Latin America will identify with them and with their musical mission. As anyone who has ever crossed a border can tell you, interesting things start happening once you start identifying with an “other”. The Rosas music inspires such beginnings… or principios, as they say.

Principios Vol. 1 is available on streaming platforms

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.