Looking Back at Fito Paez’s Breakthrough: 30 Years of ‘El Amor Después del Amor’

12 May, 2022There is a certain hour in Havana’s evenings when you can’t avoid it — an omnipresent wind like an invisible snake leads you slowly, almost without intention, to the Malecón, where night and music always fall together. This article starts on one of those nights, while I was covering a Red Bull Session in Cuba’s capital. One of the many MCs who was there noticed my accent, looked at me seriously and asked: “¿Eres argentino?” (“Are you Argentine?”) I said “yes” but he said nothing. A sharp silence grew among us and after observing me for a few long seconds, the young artist asked me, as if we shared some kind of secret: “Have you ever seen Fito Páez live? He came to Panamá some years ago, but I couldn’t afford the ticket that day and I missed him.”

That night in Havana, what kind of magic made that young MC, Seis Lunas, switch attention from his colleagues’ furious performance to the artist born 59 years ago in Rosario, the main city of Argentina’s coast? Páez’s work, spread over 26 albums and four decades has proven universal — the MCs rapping in the Caribbean know that, the new generation of Argentinian songwriters, like Mateo Sujatovich do as well, and even Netflix has decided to release a series on the rosarino. There are many sides to a prolific solo work that began in 1983, but for Spanish speakers, there’s a clear milestone: El Amor Después del Amor (Love after Love), an album that set a landmark for Latin rock and will turn 30 years old in June.

The cold numbers reflect what has been told thousands of times about the record: 200,000 copies sold in its first year – in a country which had, at that time, 20 million adults -, 11 singles, 1 million copies sold to the present day. In a sentence, it’s the best-selling record of Argentine rock. Time, nevertheless, has made the album grow beyond statistics and countries’ borders and has rooted it into Latin America’s music identity. The process that led Fito to that point, the state in which a musician is capable of writing universal songs, cannot be explained only by appealing to the way cultural industries worked during the ’90s – globalization did its part, but when Fito Paez entered the studio in 1991, he was carrying a heavy load of South American creativity with him, a heritage that nurtured what would transpire in the studio and on the final release. If we want a deeper approach to understanding this process, we must travel 600km away from Buenos Aires, follow the course of the Paraná River and stop in Rosario, in the Santa Fe province.

Identity turned into music, music turned into identity

For generations, the Paraná river has flowed between the Amazon and the Rio de la Plata leaving behind an exuberant geography and centuries of history which has flourished up and down its course. Rosario, just to mention two of its qualities, is the city where the Argentine flag was hoisted for the first time, and the birthplace of many artists who have left a mark on the country’s culture. Among them, in March 1963, Fito was born.

Music was there from the beginning: his mother was a piano concertist and her life preannounced Fito’s future in many ways. She had the piano, the musical feeling, the technique. But she passed away when Páez was only an eight-month baby. This would be the first big turn in the musician’s life — he would be raised by his grandma, great-aunt and his father, always with a piano at hand. And growing up in Rosario while playing piano meant discovering and appropriating folklorical languages that would complete his future work. Rosario is in a geographical and musical crossroad: to the north, in Corrientes province, chamamé is the main language, enter the countryside and zamba and chacarera are powerful influences, and despite being four hours away from Buenos Aires, Rosario is still an Argentinian city, and tango was always close.

When El Amor Después del Amor turned into a massive success, the layers and layers of folklorical influences, the zambas and chacareras played in the dead hours looking towards the Paraná, were still there. Proof of this is the zamba-like “Detrás El Muro de Los Lamentos” (“Behind the Wailing Wall”), in collaboration with the godmother of Argentine folklore, Mercedes Sosa, and Peruvian guitarist Lucho González, or the outro of “La Verónica”, which rhythmically and in terms of timbre is very close to Jorge Fandermole, one of the most prolific folklore writers of modern times, and another famous rosarino.

Besides, and as with a lot of Argentine music that later turned into a classic, tango’s aura can always be found if you listen closely. In this case, Fito himself discovered that the melody of “Tumbas de la Gloria” was quite close to “Vete de Mí“, by the famous tango songwriters Homero and Virgilio Expósito.

In a few words, we could say that one of Fito’s achievements was to use the resources of an international label to create music that, while circulating and being produced inside a process of globalization, employed that process to show the richness of Argentina’s folklore – or, in other words, to successfully relay an Argentine way of understanding music to a global audience.

The album’s idiosyncrasies are reflected by some of the album’s guests, such as Mercedes Sosa and Chango Farias Gómez, who millions of people listened to alongside the current hits of Latin rock. Only a few years previously this would have been impossible to imagine.

One of the musicians who made this-plot twist in Latin rock possible, and one of the few witnesses to the creation of El Amor… was the producer Fabián ”Tweety” González, who spent 11 days with Fito recording the demos in a country house in Uruguay. ”Inspiration”, he replied when I asked him about his recollection of those days. ”He was indeed inspired. I had already worked on some of his previous records, so it was natural for me to see him like that, but as days went by, I saw how inspired he was. Actually, it was very natural for us to reach the sound we were looking for. The samplers we ended up using were part of a collection I always had at hand and we both had some great recordings of keyboard parts— we took all that to Uruguay and we tried to get as close as we could to his idea”, he said.

But not only on keyboards an album is made. The recording company, Warner, placed a major bet on the album. In Tweety’s words: ”We got the greatest budget for a Fito record ever, so there was almost no limit to the budget. We finished it in London, and I could work side by side with Nigel Walker, a great sound engineer who learnt with George Martin. When we finally got it done, I knew it was something amazing. I knew it could be a platinum album, that meant, it could sell 80,000 copies, but I did not imagine all the rest”.

The rest meant 1,000,000 copies sold in Argentina alone, eleven singles out of a 13 track album and a tour that took Fito through the main capitals of South America. The album was everywhere, from parks to telenovelas to radios to public school performances. It was Fito entering a new dimension as a hugely-popular musician. Up to the present day, his songs are still used as football chants, and if you think about the Argentinian music canon, la música popular argentina, without these songs, you would find a gaping hole. That’s the scale of Fito’s work in relation to Argentina’s everyday culture. But to reach the opening track’s luminous chords, to connect millions of people with music that seemed to have been hosted in the back of a country’s mind before being released, he had to take risks in a way no other music of his generation did.

Many stages to reach love

As a music journalist and Fito follower, Federico Anzardi has interviewed the rosarino and researched him several times, but never as deep as for Hay cosas peores que estar solo (There are worse things than being alone, Gourmet Musical, 2019), a book on the rosarino‘s hardest years and his rebuilding as a human being. In November 1989, Fito, who had lost his father just months prior, was notified of the assassination of his grandmother and great aunt, the women who raised him. They were killed during a robbery in what had been his childhood home. The musician was 24 and although not yet the international figure he would once be, he was already a known artist in Argentina. The murders almost finished not only his career, but his psyche. As Anzardi’s interviews, and other research, points out, recovering from that dramatic stage was fundamental in his artistic growth. There was no possible light if Fito hadn’t wished to endure this duel and leave the pain behind.

Anzardi explains: “El Amor… is the logical result of an artist with talent, ambition and curiosity. Someone who never wanted to remain still. This album and its consequences should have arrived before, but the killings of his grandmother and great aunt distorted everything Fito had been doing since the early 80s. When those crimes happened, he was considered the artist with the greatest future in Argentinian rock. He had released a record, Giros, that had had good reviews and had performed it at Luna Park in 1985. Nobody had any doubts about his potential and everybody believed he had a lot more to give, but the killings perturbed him deeply”.

Those days newspapers spoke of a Fito who was outside of himself. He was a 24-year-old who had just become an orphan and was now facing the crimes of the women who raised him in the absence of his mother. Dressed in black, using pills to stabilize his emotions and with a radical change in the way he related to press, Paez would enter the hardest time of his life. He would not break out of this phase until years later, with enormous will and the company of crucial people, like his then partner, the rock singer Fabiana Cantilo, and the folklorist Liliana Herrero. After ‘83, Fito’s close family was reduced to his cousins in Villa Constitución, a town in the south of Rosario.

In the months which followed the crisis, Páez wrote Ciudad de Pobres Corazones, a raw album which expressed his sadness and anger and, at the same time, worked as a kind of therapy. The healing process would last until the late 80s, and the next releases, Ey and Tercer Mundo, would also feature songs which showed the process was still being undertaken.

It was necessary to await the new decade to witness the change. Even though in those days reviews did not dwell on this side of the story, Anzardi’s research allowed him to perceive in El Amor… something like a cycle coming to an end. “When Fito entered the studio to record El Amor… he was 29, but you could easily count each year double. He, as a human being, was not a rookie at all. He had already released records, and played for famous musicians including Charly García’s band, which was comparable to playing with Jordan’s Bulls in 1986″, said the journalist. Anzardi, who made 80 interviews for his book, also stresses that: “besides this, the crimes had made him grow up fast, very fast. By 1990 he met Cecilia Roth, whose love would be the final step out of the well in which he had fallen. That’s a way to interpret the album title. ‘Love after love’ is a love after a long relationship finishes, like his with Fabiana a short time before, but also the possibility of experiencing love after all of that family love that had almost stopped existing”.

Coordinates for Argentinian Rock

As already stated, El Amor…’s success can be approached by its intimate connection with Argentina’s native music, from Chango Farias Gomez’s percussion to Virgilio Expósito’s bandoneón. But besides this, because of the guests and the influences featured in El Amor… the album is also a map of Argentina’s rock canon.

To begin with, you cannot think about Fito without hearing the echoes of Charly Garcia’s phrasing, not-so-hidden in Páez’s musicality. When Charly released the triad of albums which gave him the title of “keys master” of the collective unconscious of the Nation, Fito was almost a teen who played keyboards in his idol’s band. Charly’s DNA is evident in “La Rueda Mágica” and “El Amor Después del Amor”’s arrangement and, as Tweety shows in this video, in the keyboards of “Tumbas de la Gloria”.

Following García’s godfather-like influence, the other massive creator within Argentine rock, Luis Alberto Spinetta, also left his imprint on El Amor Después del Amor. He wrote the intro to one of its major hits, “Pétalo de Sal” and sang, with his personal style, one of the album’s many sing-alongs.

Also, because of his relationship with Gustavo Cerati, Tweety Gonzalez added some sampled guitars of Soda Stereo’s leader. You can hear Gustavo’s classic PRS guitar supporting every verse of “Tumbas de la Gloria”. Soda Stereo would release, just one year later, their unexpected and astonishing Dynamo, celebrated as the band’s most risky creation.

As Federico Anzardi recalls: ”The album takes us to every significant place and name of Argentine musicality. And that’s because Fito feeds from everything. From Beatles pop as well as (legendary folklorist) Cuchi Leguizamón, tangos and bolero. In the middle, everything else. García, Spinetta or [the pioneer of Argentine rock songwriting] Litto Nebbia”.’

To summarise, the album expands across a thriving music landscape in Argentina in the 90s, a time when the country was producing what would prove to be the most universal music expressions of its history. That’s why picking a thread out of any song and following it will take you through a gallery of Argentina’s 20th century musical milestones. This was expressed in such a clear and asequible way, that 30 years after its release, millions know how to instantaneously tune in when the intro of any song starts.

Lights at both sides of the ocean

Most Argentine cultural references are produced and conceived in Buenos Aires. But, what would you see if you look at this 5 million square meter country from the lights of the Rosario-Victoria Bridge? In a kind of magic only universal music can offer, some weeks ago I visited Paez’s hometown to do some interviews and fieldwork for a book I’m working on. I stayed in a place not far from Fito’s childhood house and one morning, before the sun implored tourists to get into the hundreds of islands across the river, I went down to the hotel’s living room and met Federico and Pablo, who were working with their laptops while having a late travellers’ breakfast. We started an innocent, casual conversation, and they turned out to be huge Fito fans who were in the city only to do a stopover on their way to Cosquín Rock, the emblematic Argentine rock festival, where Páez was headlining one of the nights.

We immediately improvised an interview in which Pablo Gelso and Fede Martínez put on a very similar face to the one Seis Lunas showed that night in Havana, three years ago. ”I still remember the way my brain broke in a million pieces the first time I heard El Amor Después del Amor”, said Fede. Although he wasn’t even born when the CD filled the desks of music shops and pirate stands, he connected to the album in no time. With a sudden sense of astonishment, almost without words, Federico said: “it’s the moments, those songs take you back to moments that you can’t understand how that music is so involved in your life. Songs like “Creo”, for example, are simply shocking. The album gets to your bones”. As for Pablo, he put the album in a proper perspective: ”For me, after Clics Modernos, Charly García’s 1983 masterpiece, this is the Argentine album. It’s a milestone in our history.”

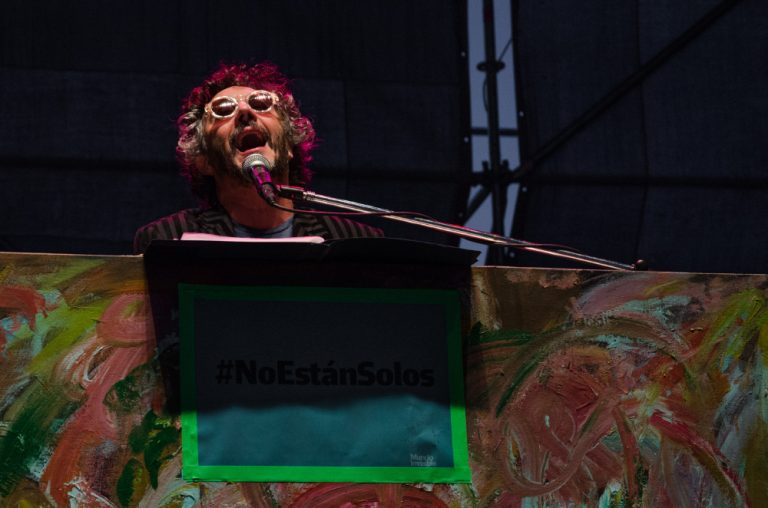

Some days later, after sharing Fito’s first massive gig in years with 70,000 others, you could tell the effect of the re-encounter in Pablo’s voice: ”While talking to you I feel goosebumps. The show was that good. He managed to create a special atmosphere like a giant cloud of emotions with thousands of people coming back to a massive show after a long time. With “Brillante sobre el mic” I cried my eyes out, it was unforgettable. Fito creates a kind of bond with you that makes you get lost in space-time. And only you are present in that moment”.

Meanwhile, Fede said: “We traveled from Rosario to Córdoba listening to El Amor…, It was just beautiful. And the show was divine. Sometimes when some music is too massive or popular we tend to think that it’s over-rated. But no: When he played “El amor después del amor” at Cosquín, and you could see the sunset, the mountains around the stange, and feel that happiness in so many people… The sensation was… damn, what else can I ask?”

And as if it was taken out of Anzardi’s book, Fede’s last thought on the 1992 masterpiece can work as an epilogue in which thousands of El Amor…-related experiences merge: “I think love after love is what’s happening to us after the pandemic and Fito’s message has a considerable parallelism with what we experienced these past years — we are coming out of this, the situation is changing and the hope is reborn again. What we experienced was not the end. We’re still here, fighting for something better”.

After a pandemic and amid a war that will change our world in ways we still cannot guess, what is left – like Páez did, like we all will – is to start again and re-find ourselves. Whether looking at the Malecón’s resplendence or towards Rosario’s bridge glow, El Amor Después del Amor leitmotif is equally valid: “lights always rouse within the soul”.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.