Preserving the African Traditions of Colombia’s Pacífico with Eryen Korath and Cantares del Pacífico

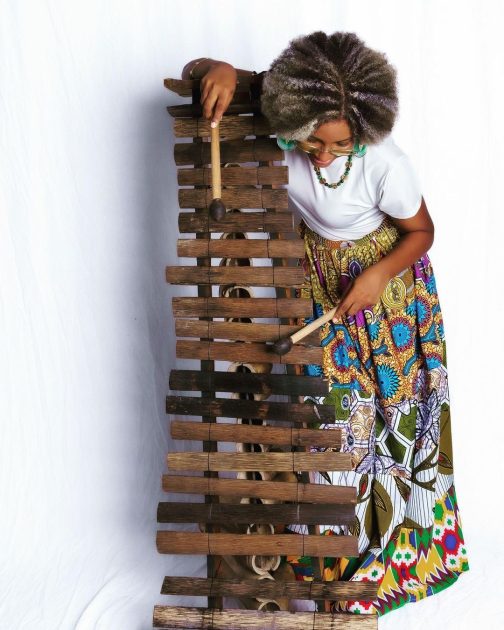

22 April, 2022She’s more than Grammy-winner Petrona Martínez’s marimba player… she’s the Queen of marimba de chonta, and her song has only just begun.

Nietzsche was right when he said “without music, life would have no meaning, existence would be a mistake”. Music or musicality has always accompanied humans, either to give comfort, to elevate our mood, or in pursuit of knowledge. Yet its importance is more than the hundreds of aphorisms that we could use to refer to it. Its importance is also in how it serves as a mechanism for the safeguarding of customs and traditions. In vulnerable and diasporic communities such as the Afro-descendents in Colombia’s Pacífico region, this mechanism is particularly vital. The Pacífico is one of the most important regions of Colombia, and comprises four administrative divisions: the departments of Cauca, Chocó, Nariño and Valle del Cauca. It is a humid paradise of immense biodiversity. Its beaches, rainforests, swamps, and impenetrable rivers and mangroves stand as the backdrop to an equally diverse cultural ecosystem. These unique sonic environments, or “soundscapes”, have been semiotically merging and mixing since the 16th century with traditions brought from Western Africa.

Eryen Korath, a young Afro-Colombian musician and lawyer, not only holds the title of “Queen of the Marimba de Chonta” (a version of the marimba native to the Pacífico), but also holds the valuable responsibility of safeguarding and promoting the tradition of her ancestors. She is a spokesperson for the inclusion of the African descendents of slavery in Colombia’s national cultural stage and, as such, she knows first-hand the importance of cultural preservation. Through her musical prowess she has become a cherished representative of her hometown, performing its music in the United States, the Netherlands, Panama, and Ecuador. Korath even took part in the opening of the Colombian Embassy in Ghana. She is currently the leader of the musical group Cantares del Pacífico, and director of the foundation which bears the same name. Most recently, she has featured on Petrona Martínez’s album Ancestras, which won a Latin Grammy. Her contribution, the track “Bobby (Son Palenque-Rumba Pacífica)“, is a stunning mix of sounds from the two distinct Afro-Colombian regions of the Costa and the Pacífico. But she’s still just getting warmed up.

Born and raised in Buenaventura, Colombia’s primary seaport, Korath benefited from the work of non-profits in the city dedicated to promoting the traditional folkways of the Pacífico among its youth. At the age of five she began to study traditional instruments such as the guasá (a rattle-like percussion instrument similar to maracas which is used commonly in the arrullo style of playing) and the cununo drum. She also distinguished herself early on in traditional dance and singing. In the end she was also able to master the marimba de chonta, an instrument often referred to locally as el piano de la selva, “the jungle piano”. Being a female marimba player would not be easy, however. Not only did she have to face the complexities of the instrument itself, but she also had to navigate a minefield of restrictive gender roles which held that marimba playing was the strict purview of men. The region’s folk cosmologies have always held that the marimba has a power that is equal to evil and carries the potential to dispel it… such a power, goes the traditional wisdom, is too much for female hands. In his Rites, Rights & Rhythms: A Genealogy of Musical Meaning in Colombia’s Black Pacific, Michael Birenbaum Quintero writes: “The devil and marimba music are also tied to ideas of gender. Drums and the marimba are understood as instruments of antagonistic engagement with the devil and wild nature spirits, which is seen as the role of men.”

The fact that Korath was named “Queen of the Marimba de Chonta” in 2016 at the Petronio Alvarez Festival – a festival which highlights the music of the Pacífico – not only demonstrates that women can participate in music as much as men. It also demonstrates, as Korath declares, that “as women of the Pacífico we are able to represent our territory and open the way so that there are more spaces for participation and inclusion for other women”. What is notable is that this way forward is opened not through rejection of tradition, but through the embrace of it.

The traditional marimba de chonta is constructed according to precise specifications. It has 23 bars that are extracted during the waning moon from the native peach palm, called chonta – hence the name. Next, there are 23 sections of tube made from the endemic guadua bamboo variety, which function as resonators. The bars are struck with a mallet with one of its ends lined with natural rubber. Commonly it is played in pairs, one who plays requinto, providing rhythmic foundations, and the other who plays the bordón, or melodic accompaniment. On some occasions it can be played by up to three people. Regarding the spiritual import of the instrument’s construction, Korath says that when a traditional luthier builds a marimba they take into account specific rituals. There is deference to natural processes: the cultivation of the chonta and the lunar cycles. When the marimba de chonta is built, they keep in mind the sounds of water, whether falling in the form of rain or the aquifer sounds emitted by hydrographic basins or rivers. These aquatic acoustics are utilized in the traditional tuning of the instrument, with some Luthiers dripping drops of water on each resonator joint in order to alter the pitch of a bar so as to establish the appropriate pitch of the subsequent bar.

Korath emphasizes that the sound of the Pacífico is not only defined by the marimba. “The marimba de chonta is just one more element of everything else that makes up music from the Colombian Pacífico. The voice and other instruments are also protagonists… The importance of all these elements lies in the fact that our songs and rhythms are recounting our experiences and our motivations, our deepest pains and joys. All this is reflected in the four main [musical] rites that we have, which are: el arrullo [“lullaby”], which is performed with drums and marimbas and is dedicated to our saints, el currulao where the men play the marimba while the community dances, the women sing and stories are told; el chigualao, which are a capella mourning songs for a child’s wake, and el alabao, which are heartfelt funerary melodies for adults.” The thrust of these ceremonial songs are communal, however, individually speaking, “there is also an important actor in this narrative: women. They preserve tradition, they are part of everyday life and they don’t know it.” Being that actor is something more than mere re-enactment: “My work and that of my group […] seeks to vindicate all of them… that’s why, more than stage musicians, we are conservation musicians.”

The opportunity to participate in Petrona Martínez’s Ancestras was a formative moment for Korath and her group, Cantares del Pacífico. The conceptual album unites the greatest exponents of Afro-diasporic music from different countries. Korath was joined by Susana Baca from Peru, Angelique Kidjo from Benin, Nidia Góngora from Colombia, Aymée Nuviola from Cuba, Xênia França from Brazil, and Flor de Toloache from New York, among others. It is a step in a process of awakening; of both realizing the global contexts of the Pacífico’s traditions and of sensing the strength and dignity of its particularities. “This is an honor for me,” says Korath, “Teacher Petrona is a representation of the safeguarding work that the elderly have [always] been doing in our Afro-descendant communities.”

The experience of Eryen Korath tells us about the importance of the collective memory of the communities of the Pacífico, of a unique sound landscape that fascinates academics and aficionados, and of cultural dialogue through which a group identity can be maintained or established. These are the reasons why UNESCO decided to include marimba music, songs and traditional dances from the Pacífico on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This approach to officially recognizing cultural patrimony allows us to see such regions as spaces for cultural assembly and conciliation. The truth is that the history of violence and inequality in the Pacífico has forced new generations to break away from their roots in a traumatic way. It is one of the richest regions of the country in terms of resources, yet one of the poorest in terms of infrastructure and investment. Korath is aware of this.

She is also aware that the port of Buenaventura, frontispiece of the Pacific receives everything, “the good and the bad.” Yet, like the marimba player with their mallet in hand, ready to chase away the devil, we have a choice of what to keep and what to dispel. “The music of our region offers the most favorable side of the coin for the youth of Buenaventura,” she says. Her words are a reminder that throughout the processes of configuration and deconfiguration that occur in this world, whether due to external influences, violence, or other musical styles, the most solid part of culture is expected to emerge. That is, the will to resist and prevail.

Yulia Pereira is a Colombian artist, designer, and writer. Her work focuses on Latin America, the Caribbean, and the African diaspora.

Jeremy Ray Jewell hails from Jacksonville, FL. His website is jeremyrayjewell.com.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.