Religious Rhythms: The Afro-Brazilian Music of Candomblé

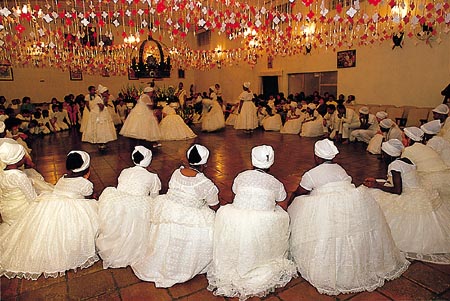

19 April, 2011Accompanied by highly percussive drumming, the ritualistic ceremonies of the Afro-Brazilian candomblé religion have distinctly shaped the musical soundscape of Brazil, influencing many contemporary styles such as the samba and bossa nova.

Indicative to a popular dance found in the slave plantations of the Bahian region of North-Eastern Brazil (candombe), the term candomblé has become a generic term to designate the religion itself and the locality of cult practices. Beginning in the seventeenth century, most slaves who arrived on Brazilian soil descended from various different ethnic groups of West Africa – such as Yoruba (nagô), Ewe, Fon (gege), Bantu and the Congo-Angola nations. However, all maintained candomblé religion as a primarily ritualistic practice, reflecting many characteristics of the cultural practices of their ancestors. One of the main features of the candomblé religion is the inherent belief of the axé – a magic-sacred force that assures dynamic existence and controls what happens in quotidian life. The axé of each cult center and of the gods (orixás) is implanted in the initiating devotee from the supreme leader (ialorixá, babalorixá or pai/mae de santo).

Candomblé Ritualism and Sacred Instruments

Music and the use of percussion is a crucial element in candomblé ceremonies especially as a vehicle in which the orixás are appeased. During rituals, practitioners regard the music as axé‘s embodiment and view the musical practice as the voices of the deity-like orixás. There are usually three different types of drums used in religious ceremonies known as the atabaque. Similar in many ways to congas in their barrel-shaped physicality, the drums are played with thin sticks and hands alternately. There are three different sizes of drums including the lê, rumpi and the rum. The agogô bells as well as the xequerê, a medium-sized gourd covered with strung beads establish a repeated, syncopated pattern whilst the rum, the biggest drum leads the arrangement, commanding the lê and the rumpi.

The main purpose of the atabaque is to hypnotize and entrance individuals and whilst the drummers themselves are never possessed by the orixás, they watch and communicate with the priests and dancers responding appropriately with their music. There is a vast repertoire of complex drum patterns that are connected to candomblé ritualism including music that calls upon the orixás, music for sending them away and so forth. The rhythmic pattern performed is chosen from a range of complex patterns, all belonging to classified groups of rhythm including the nago rhythm (influenced by Yoruba traditions) played by agidavis (drum sticks) and Congo-Angola rhythms, performed with open palmed hands. The rhythms are complex and syncopated, creating a complex matrix of sound when each individual part is added to the group. Musical features such as timbre, tone, pitch and dynamics are also sensitive qualities in a ceremony, providing a guidance in which those taking part will mimic the movements that they believe imitate the orixás.

Many practitioners believe that the instruments are vested with healing powers and possessed with axé force. The atabaque revere such prowess in the candomblé religion and culture that the instruments are gendered as either male or female as well as other dichotomies as happy/sad and hungry/full or dressed/undressed. Even the making of the instruments requires a trained specialist and a sacrificed animal for the drum-skins which has to be fully dried and shaved prior to being placed on the drum. Once an instrument has been made, a special offering occurs where the power and spirituality of the axé is transmitted to the drum by means of a special ceremony involving the pouring of blood over the drum heads.

The atabaque also provide a rhythmic accompaniment to a variety of ceremonial songs. Singing the verse is usually the leader who uses semi-spoken dialogue in amongst the melody. In the chorus, initiates and fellow practitioners sing whilst dancing and clapping at the same time. With each repetition, the intensity and tempo of the songs increase once initiates begin to experience the axé power through spirit possession of the orixás. Once they have reached this particular state, the singing ceases and only the atabaques and agogô bells remain, providing a continuous rhythmic flow for the remainder of the ritual enactment.

Candomblé Music and Its Rise as a Secularised Popular Music

Although music remains an intrinsic part of candomblé religion, it has also made its way into mainstream culture as a popular musical form. Popularizing the sacred sounds are the afoxé groups, a carnival-type fraternal organization who followed in the footsteps of the irmandades, a Catholic lay group, formed in Salvador in the seventeenth century in avocation for African traditions. Although afoxé groups were frowned upon for their radical use of sacred music, one group known as Filhos de Gandhi (Sons of Gandhi) helped break such social negation, particularly through their celebration of their Afro-Brazilian heritage. However, due to the 1964 coup, resulting in various governmental restrictions, afoxe groups and the public performing of candomblé music had severely declined. A decade later, renowned musician Gilberto Gil played a significant role in the resurgence of afoxé ideology when he joined Filhos de Gandhi, quickly becaming a leading member. Part of Gil’s advocation of afoxé music can be found on his album Refavela (1977), specifically the song ”Patuscada de Gandhi’ (Revelry of Filhos de Gandhi), where Gil adds a spiritual quality by calling out to many of the orixás. The album itself is an unequivocable homage to his ancestral routes, stemmed in many ways by his participation in FESTAC – the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture in Lagos, Nigeria in 1977. Also ground-breaking was Gil’s introduction of the well-known candomblé Ijexa rhythm that today is a distinct feature of unique styles like the samba and the bossa nova.

Today, candomblé religion is as popular as ever in Brazil, as well as most of South America and European countries such as Germany, Italy and Spain. In terms of its music, not only can it be heard in the ceremonies taking place in the thousands of cult centres (i.e. temples) but also in the vibrant and colourful carnival settings across Brazil, blurring the boundaries in which music is performed and by doing so, secularizing the sacred.

Find out more about Brazilian Music

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.